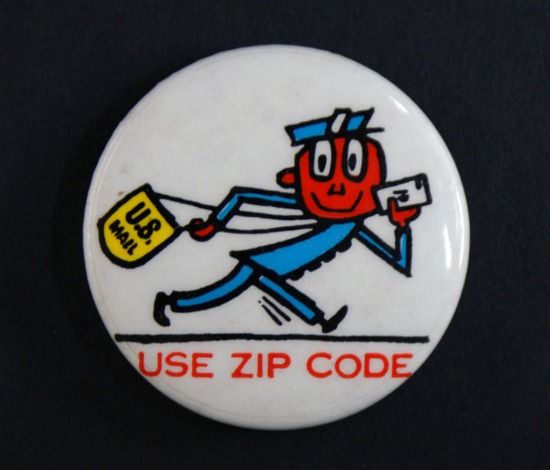

Mr. Zip and the Brand-New ZIP Code

When the Post Office debuted the ZIP Code, they introduced a friendly cartoon to be its lead salesman

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20111115040004Transitad-small.jpg)

One of the most important breakthroughs in modern communication lies in an overlooked place. It’s printed onto envelopes, just below the address. Although we think nothing of the ZIP Code these days, when it was rolled out in the 1960s, it was a novel and challenging concept for many Americans. And so, to help sell the ZIP Code, the Post Office Department introduced a friendly new mascot for the public campaign: the grinning, lanky Mr. Zip.

The National Postal Museum has now launched a new site, created by museum curator Nancy Pope and intern Abby Curtin, that celebrates the history of the ZIP Code campaign and its speedy mascot.

That history begins, Pope says, in the early 1960s, when growing mail volume and suburbanization had strained the mail system. Postmaster General J. Edward Day and others were convinced of the need to automate the sorting process. “They wanted to move to a mechanized process,” Pope says. “The ZIP Code system was essential in getting the machines to work.”

The Zone Improvement Plan (ZIP) assigned a unique five-digit number to each post office in the country, and sorting machinery used the codes to directly route mail from one city to another. “Without the ZIP Code, mail has to be processed through a series of processing centers. So if you’re going from Boston to San Francisco, you have to go through the Boston center, the New York center, the St. Louis center, and the Omaha center, until you finally get to California,” explains Pope. “But with the right ZIP Code, it gets put straight into the mail that’s going to San Francisco.”

Despite the obvious benefits of the ZIP Code system, officials feared that its 1963 roll-out would meet resistance. “Americans in the late 50s and early 60s are having to memorize more numbers than they had before,” Pope says, noting the implementation of phone area codes and the growing importance of Social Security Numbers.

To preempt this problem, the Post Office Department embarked on a public campaign to convince people to start using the ZIP Code, and likely named the system ‘ZIP’ to capitalize on its main selling point: speed. The campaign used radio, print and television advertisements to drive home this association, with crooked line frequently representing the old system and a straight arrow the new one.

With a dashing gait and a child’s smile, Mr. Zip’s presence in advertisements, post offices, and on mail trucks linked the idea of quickness to a cheerful, human face. “These homey touches were to help people look at the ZIP Code not as a threatening thing, but as a happy, speedy thing that’s going to make their lives easier,” Pope says.

Gradually the public caught on. “It took a little while—they didn’t hit a high percentage of people doing it for a couple of years—but they finally did get people convinced,” Pope says. By the late 1970s, the vast majority of mail users were comfortable using the numbers, and Mr. Zip was gradually phased out.

But the wide-eyed Mr. Zip lives on. He still appears on the Postal Service’s ZIP Code lookup Web page, and his story is detailed at the Postal Museum’s new site. Next month, the Museum is also debuting a new exhibition, “Systems at Work,” which explores the evolving technology behind the postal delivery process. Learn more about Mr. Zip and the ZIP Code starting December 14th at the National Postal Museum.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)