Amy Henderson: “Downton Abbey” and the Dollar Princesses

A curator tells of 19th-century American socialites, who like Cora Crowley, found noble husbands and flushed Britain with cash

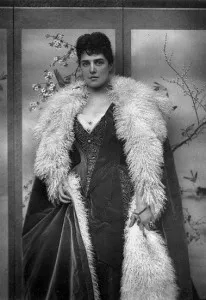

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120314112005Lady-Curzon-small.jpg)

This post is part of our ongoing series in which ATM invites guest bloggers from among the Smithsonian Institution’s scientists, curators, researchers and historians to write for us. Today, the National Portrait Gallery’s cultural historian Amy Henderson, inspired by the Cora Crawley character on PBS’s “Downton Abbey,” traces the real-life stories of few American socialites who married into British nobility. She last wrote for us about Clint Eastwood’s visit to the National Museum of American History.

In a recent New York Times interview, marking the end of “Downton Abbey’s” second season, series creator Julian Fellowes discusses the Gilded Age “dollar princesses” who were the models for the character of Cora Crawley, the rich American who marries the Earl of Grantham.

“I’ve read all these things,” Fellowes told the Times, “like Cora is supposed to be Mary Leiter. She isn’t really – she’s one of that genus, of which Mary Leiter is a famous example.”

I broke into a wide smile as I realized that Fellowes had given me a slim, but very real academic connection to this wonderfully addictive sudsfest. Just before joining the staff at the Portrait Gallery in 1975, I was hired by Nigel Nicolson to research a biography he was writing of a young Chicago woman who became Vicereine of India at the turn of the 20th century—Mary Leiter Curzon.

Heir to the Marshall Field retail business her father co-founded, Mary Leiter moved with her family to Washington, D.C. in the 1880s. She was an immediate social sensation, a beautiful “swanlike” figure who quickly became close friends with the young first lady Frances Cleveland, wife of Grover Cleveland. Leiter’s social success followed her to London, where she met Lord George Curzon. Married in 1895, she and Curzon moved to Bombay three years later when he was appointed Viceroy of India. Mary’s elevation to Vicereine remains the highest position an American woman has ever held in the British Empire.

The centerpiece event of the Curzons’ tenure was the 1902 Delhi Durbar, organized to celebrate the coronation of King Edward VII. Mary wore an astonishing dress designed by the House of Worth known as “the peacock dress.” The gown was an extravagance of gold cloth embroidered with peacock feathers, and Mary wore it with a huge diamond necklace and a pearl-tipped tiara. One could only imagine the eye-popping reaction of Violet, the Dowager Countess of Grantham (played by Dame Maggie Smith), to such an over-the-top confection floating down Downton’s halls.

Mary Leiter Curzon was one of perhaps 350 wealthy young American women, Fellowes estimates, who married into the cash-poor British aristocracy between 1880 and 1920. Winston Churchill’s mother was an early example. The daughter of a New York financier, Jennie Jerome married Lord Randolph Spencer-Churchill in 1874. She has been called the forerunner of the wealthy American women who came to England in the late 19th century to marry titles—a species novelist Edith Wharton immortalized in The Buccaneers. Jennie was remarkably lovely, and her portrait was in high demand because of her status as one of the era’s leading “PB’s,” or “professional beauties.” According to Consuelo Vanderbilt, “Her grey eyes sparkled with the joy of living and when, as was often the case, her anecdotes were risqué it was with her eyes as well as her words that one could read the implications.”

The vivacious Jennie had numerous affairs that included even the Prince of Wales, and embraced the idea that living well was the best revenge: “We owe something to extravagance,” she pronounced, “for thrift and adventure seldom go hand in hand.”

Another of the famous “dollar princesses” was Nancy Langhorne, a renowned Virginia-born beauty. While her sister Irene married Charles Dana Gibson and became a prototype for the Gibson Girl, Nancy moved to England, where she was sought after socially for her wit as well as her money. In 1879, she married William Waldorf Astor, who had also been born in the United States, but had moved to London as a child and been brought up in the manner (and manor) of the English aristocracy. After their marriage, the Astors moved into Cliveden, a country house much like Downton Abbey, and which, during the Great War, served like Downton as a hospital for convalescing soldiers.

Lady Astor’s real distinction was to be elected to Parliament in 1919. Her husband served in the House of Commons, but became a member of the House of Lords when he succeeded to his father’s peerage as Viscount Astor. Nancy Astor then ran and won his former seat in the Commons, becoming the second woman to be elected to Parliament but the first to actually take her seat.

These American-British marriages were all the rage at the turn of the 20th century, and an entire industry emerged to help facilitate matchmaking. A quarterly publication called The Titled American listed the successfully anointed ladies, as well as the names of eligible titled bachelors: “The Marquess of Winchester,” one citation read, “is 32 years of age, and a captain of the Coldstream Guards.” It was a resource much like Washington’s social register, The Green Book, or contemporary online resources like Match.com.

Novelist Wharton, a member of New York’s Old Guard, relished writing about the nouveau riche as a “group of bourgeois colonials” who had made a great deal of money very quickly in industry. Denied access to social position by the established upper crust, they crossed the Atlantic and acquired titles that transformed them, she wrote, into “a sort of social aristocracy.”

In acquiring prestige by title, the “dollar princesses” are estimated to have contributed perhaps $25 billion to the British economy in today’s currency. These wealthy American women are also credited with helping to preserve such stately English homes as Highclere, the actual country house featured in “Downton Abbey.”

The accommodation between old status and new money is well-reflected in this exchange between Cora (played by Elizabeth McGovern), the Earl of Grantham’s American wife, and Violet, the Dowager Countess:

Cora: “Are we to be friends then?”

Violet: “We are allies, my dear, which can be a good deal more effective.”

Ok, for fun—two other favorite Dowager Countess quotes:

—“I couldn’t have electricity in the house, I wouldn’t sleep a wink. All those vapors floating about.”

—“What is a weekend?”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)