Lalla Essaydi: Revising Stereotypes at the African Art Museum

A new solo exhibition by Lalla Essaydi challenges Western and Muslim perceptions of women’s identities

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120509020011essaydithumb.jpg)

Every year, Lalla Essaydi returns to her childhood home in Morocco: a huge, elaborate house that dates back to the 16th century. Occasionally, she goes alone. More often, she brings 20 to 40 of her female relatives with her.

“There’s a part of that house that was for men only,” Essaydi, who now lives in New York, explains. “And there is a specific room that women were not allowed in, or were only allowed when there were no men in the house.”

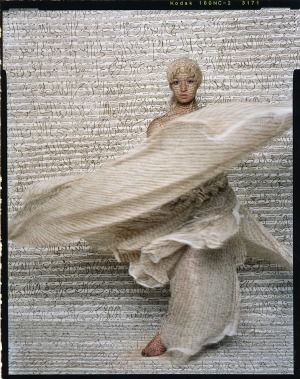

Essaydi and her sisters inhabit this room for weeks at a time. She does a rather odd thing there. She covers the space in white cloth and starts writing Arabic calligraphy in henna on the cloth, on the walls and even on the women, in a free flowing to the conversation and activities around her. At the end, she shoots photographs of the women. But to Essaydi, the period of setting up the room and being with women is equally, if not more important, than the end result. It is an act of rebellion against the world she grew up in: filling a room that traditionally belonged to men with the words of women, written in calligraphy, an art that was historically restricted to men, and in henna, a dye used to adorn women.

“The experience is so intense that the photography doesn’t really convey what happens during these times,” Essaydi says.

In an effort to capture this experience, the exhibition “Lalla Essaydi: Revisions,” on view at the National Museum of African Art starting today through February 24, brings together Essaydi’s well-known photographic series with her rarely exhibited paintings and a video of the process. It is the first solo exhibition to bring together these different media. The labyrinth of rooms, which includes an intimate section filled with silk-screened images of women (some of them naked) on banners, encourages the visitor not simply to observe, but to engage with the art.

“It really does invite you into the space,” says guest curator Kinsey Katchka. “It creates a dialogue between the viewer and the artist and the model, too, who is included in the conversations during the process.”

Other photographic series on display are Essaydi’s “Harem” series, shot in Marrakesh’s historic Dar el Basha Palace, and “Les Femmes du Maroc,” in which she recreates 19th-century European and American paintings of an Orientalist fantasy. Her paintings, too, emphasize the disconnect between the Western romance of the East and the reality of women’s lives.

Essaydi is well-positioned to scrutinize these different cultural perspectives. Born in a Moroccan harem, she has lived in Paris, Saudi Arabia, Boston and New York. Her father had four wives and her mother covered her face with a veil for most of her life. After experiencing the harem life firsthand, Essaydi is troubled by the Western depiction of a sexual space full of nude, lounging women.

“I can hardly imagine my mother and sisters walking naked all day long in our home,” she says. “Because our religion allows the man to marry more than one woman, the harem is just a large house full of children. And everyone has chores in the house.”

But now, the Western fantasy has flipped. “Instead of seeing the women as naked and walking in a harem, now we see women as being oppressed and covered, without any say, and she’s not doing anything about it,” she says, emphasizing the assumption that oppressed women passively accept their fate without resistance. “I am one of the millions of women who are fighting every day for their life and their identity.”

But Essaydi’s meditations on objectified Arab women always seem to return to that childhood home. At the heart of her work is her dialog with her cousins and sisters, as they struggle to make sense of their own upbringing and identity.

“It really changes our life,” she says. “Every year we get together and talk about things that were taboo in our culture. We meet even if I’m not shooting. It’s just become a tradition.”

“Lalla Essaydi: Revisions” opens today at the African Art Museum and runs through February 24, 2013.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ATM-aviva-shen-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ATM-aviva-shen-240.jpg)