Lincoln’s Assassination, From a Doctor’s Perspective

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120612021014Leale-cuff-web.jpg)

It was about 10:15 p.m. on April 14, 1865, when John Wilkes Booth snuck up behind President Lincoln, enjoying “Our American Cousin” at Ford’s Theatre, and shot him point-blank in the head. The assassin brandished a dagger and cut Maj. Henry Rathbone, a guest of the president’s, before leaping to the stage, yelling “Sic semper tyrannis,” before fleeing.

According to most surviving accounts, the scene was sheer chaos. “There will never be anything like it on earth,” said Helen Truman, who was in the audience. “The shouts, groans, curses, smashing of seats, screams of women, shuffling of feet and cries of terror created a pandemonium that through all the ages will stand out in my memory as the hell of hells.”

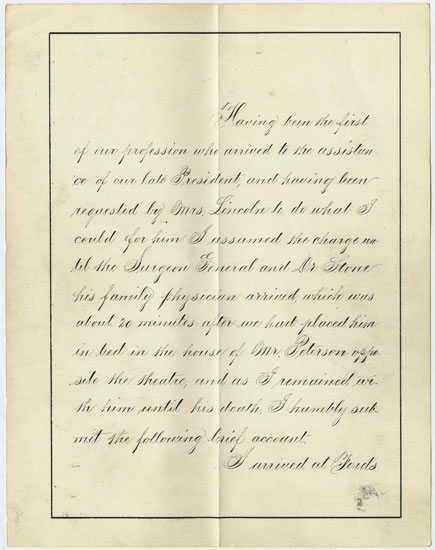

A newly discovered document, however, offers a different perspective. Late last month, a researcher with the Papers of Abraham Lincoln—an online project that is imaging and digitizing documents written by or to the 16th president—located a long-lost medical report at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. The report was written by Dr. Charles Leale, the first doctor to tend to the dying president. Leale, a 23-year-old Army surgeon, ran from his seat in the audience to the president’s box, a distance of about 40 feet away.

The first page of Leale's 22-page medical report, found at the National Archives. Image courtesy of the Papers of Abraham Lincoln.

In the report, Leale describes what happened next:

“I immediately ran to the President’s box and as soon as the door was opened was admitted and introduced to Mrs. Lincoln when she exclaimed several times, ‘O Doctor, do what you can for him, do what you can!’ I told her we would do all that we possibly could.”

When I entered the box the ladies were very much excited. Mr. Lincoln was seated in a high backed arm-chair with his head leaning towards his right side supported by Mrs. Lincoln who was weeping bitterly. . . .

While approaching the President I sent a gentleman for brandy and another for water.

When I reached the President he was in a state of general paralysis, his eyes were closed and he was in a profoundly comatose condition, while his breathing was intermittent and exceedingly stertorous.”

Although the full report does not shed much new light on the assassination or how doctors attempted to treat Lincoln’s fatal injury, it is, no doubt, an amazing find. Daniel Stowell, director of the Papers of Abraham Lincoln told the Associated Press last week that the document’s significance lies in the fact that “it’s the first draft” of the tragedy.

I was particularly interested in what Harry Rubenstein, chair of the National Museum of American History’s political history division, thought of the firsthand account. Rubenstein is curator of the museum’s permanent exhibition on presidents, “The American Presidency: A Glorious Burden.” He also curated the much-acclaimed 2009-2011 exhibition “Abraham Lincoln: An Extraordinary Life.”

The museum holds in its collections Leale’s bloodstained cuffs that he wore the night of Lincoln’s assassination and the ceremonial sword that Leale carried while serving as an honor guard while Lincoln’s body lay in state at the White House and the U.S. Capitol. (The estate of Helen Leale Harper, Jr, granddaughter of Dr. Leale, bequeathed both to the Smithsonian Institution in 2006.)

Rubenstein is fascinated with the subdued tone of the report. “You are used to all these reports of mayhem and the chaos and the confusion,” he says. “Here, you are seeing it from the view of somebody who is trying to gain and take control.” The curator points to Leale’s choice of words, “the ladies were very much excited,” as one of the report’s understatements. “A lot of the emotion is removed from this, and it is a very clinical look at what took place, in comparison to others,” says Rubenstein.”To me, it is this detached quality that is so interesting.”

Leale gives a detailed description of looking for where Lincoln’s blood was coming from and assessing his injuries. The report chronicles the president’s condition up until the moment shortly after 7 a.m. the next day when he dies. “It is just interesting to see the different perspectives of this one pivotal historical moment,” says Rubenstein.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)