Reclaiming the Edge: Exhibit Compares Waterfront Development Around the World

From Shanghai to Los Angeles to D.C., the Anacostia Community Museum’s looks at recent efforts to reclaim urban rivers

![]()

From the exhibit “Reclaiming the Edge,” kids explore the Anacostia River in the heart of Washington, D.C. Photo by Keith Hyde, US Army Corps of Engineers, 2011 Wilderness Inquiry, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Shanghai, London, Louisville, Los Angeles, Washington, D.C. and Pittsburgh all have one thing in common: water. Specifically, the cities share the community-defining feature of an urban waterway. In the nation’s capital, the Anacostia River helped drive settlement in the region but after decades of degradation, it became known as the “Forgotten River.”

Now the Anacostia Community Museum has taken on the ambitious task of organizing two years of comparative research to create its exhibit, “Reclaiming the Edge: Urban Waterways and Civic Engagement,” examining the challenges and successes of rivers running through city spaces.

At 8.5 miles long, the Anacostia River has an expansive watershed of 176 square miles that reaches into Maryland and parts of Virginia. Paired with the Potomac, the river helped attract early development. Gail Lowe, an historian at the Anacostia Community Museum, says the river has been a major commercial and industrial conduit. “As more of the city developed toward the west and toward the Potomac River,” she says, “the Potomac sort of became the poster piece for this region.” Meanwhile, it’s sister, the Anacostia continued to suffer neglect.

The Blue Plains Sewage Treatment Plant located on the Anacostia River. Photo by Dick Swanson, April 1973. Courtesy of the U.S. National Archives

Writing for the Washington Post, Neely Tucker says, “To most Washingtonians, the Anacostia is a very remote presence — that dirty glop of water under the 11th Street Bridge, the Potomac’s ugly cousin, the barrier that sets off the city’s poorer sections from Capitol Hill.”

But the river was not alone in its scorned status. The Los Angeles River, for example, has been so neglected many residents don’t even know it was there. “The Los Angeles what?” they reportedly responded, according to a 2011 Time magazine piece in which an intrepid reporter kayaked down the forsaken waterway.

Over the course of two years, Lowe helped lead a research effort to explore other such urban rivers. “We identified through our preliminary research, cities that had similar challenges that the Anacostia River here was facing and then explored some of the ideas and solutions that they had taken,” says Lowe. “So, with Los Angeles, we were looking at a forgotten river, forgotten because you really couldn’t see it at all–it’s been enclosed in a pipe–and also a river that flowed through a locality that has a very diverse population.”

Strengthened by the support of both the environmental and historic preservation movements, waterfront redevelopment became a popular way for cities to experiment with so-called spot development. Serving as both public gathering points and tourist attractions, a thriving waterfront can be an engine of commercial and social life in a city.

The exhibit features the museum research team’s findings as well as artwork inspired by each river, including murals, kinetic sculptures and fine arts photographs that recast the urban rivers as works of art.

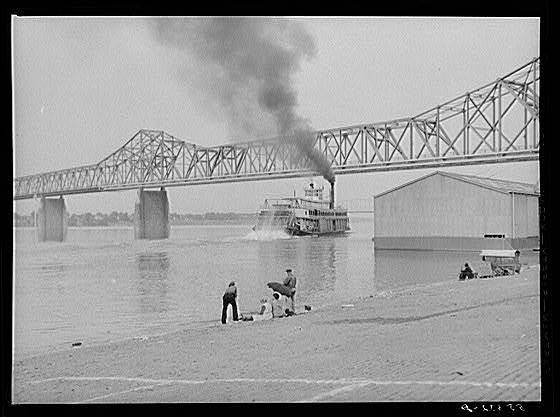

Now home to an ambitious redevelopment project, the Louisville waterfront once looked like this. 1940. Photo by Marion Post Wolcott. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

One particularly successful project that the exhibit looks at is the redevelopment of the Louisville waterfront. Part of a growing trend of public-private partnerships, the project helped attract commercial and residential uses as well as enhance public spaces. Michael Kimmelman writes in the New York Times, “Getting there requires crossing several busy roadways, and the park is practically inaccessible without a car. But it’s popular. A former railroad bridge over the Ohio River will soon be opened to pedestrians and bikers.”

Overall, the project, managed by the Waterfront Development Corporation, has been an improvement. Lowe says, “They’ve been very successful in creating a place where people walk and bike and gather, children play, concerts are held. The development has been able to put in some housing, some business properties that don’t take up the waterfront but really add to it.”

In agreement that the development has been a step forward, Kimmelman writes that it needs the infrastructural support of an improved public transit system to reach more people.

The problems that face urban waterways are many, says Lowe, but the potential is equally great. The Anacostia River faces all of these challenges. Recent efforts to clean up the decades of pollution have certainly helped, but Lowe hopes the exhibit can help catalyze further action. “The exhibition is not an end in itself, it is part of a longer commitment on the Anacostia Community Museum’s part to study, explore and explain environmental issues and ecology,” says Lowe.

In addition to the artwork, which calls on viewers to appreciate the beauty of the studied waterways, the exhibit includes sections to assess your impact on the Anacostia River’s watershed. Through the examination of individual impact, community involvement and private-public partnerships, the exhibit underscores one of Lowe’s takeaways: “It’s going to take all of us to restore the waterways.”

“Reclaiming the Edge: Urban Waterways and Civic Engagement” runs through September 15, 2013.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)