Bangs, Bobs and Bouffants: The Roots of the First Lady’s Tresses

Michelle Obama’s modern look has a long history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f3/89/f3891887-09ce-45bc-8d23-bf9f2424ba0b/obama_bangs.jpg)

When Michelle Obama debuted her new hairstyle for the inauguration, her “bangs” stole the show. Even seasoned broadcasters spent a surprising amount of time chattering about the First Lady’s new look. In all fairness, there was also much speculation about the president’s graying hair—but that was chalked up to the rigors of office rather than a deliberate decision about style.

“Bangs” first made headlines nearly a century ago when the wildly popular ballroom dancer Irene Castle bobbed her hair. Castle and her husband Vernon were the Fred-and-Ginger of the 1910s and became famous for making “social dancing” a respectable pursuit for genteel audiences. They were embraced as society’s darlings and opened a dance school near the Ritz Hotel, teaching the upper crust how to waltz, foxtrot, and dance a one-step called “the Castle Walk.”

Irene Castle became a vibrant symbol of the “New Woman”—youthful, energetic, and unfettered. She was a fashion trendsetter, and when she cut off her hair in 1915, her “bob” created a fad soon mimicked by millions. Magazines ran articles asking, “To Bob or Not to Bob,” and Irene Castle herself contributed essays about the “wonderful advantages in short hair.” (Although in the Ladies Home Journal in 1921 she wondered if it would work well with gray hair, asking “will it not seem a bit kittenish and not quite dignified?”)

The “bob” suited free-spirited flappers of the 1920s: it reflected women’s changing and uncorseted role in the decade following the passage of woman’s suffrage. In 1920, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s short story, “Bernice Bobs Her Hair,” evoked this transformation by describing how a quiet young girl suddenly morphed into a vamp after her hair was bobbed. In years before women had their own hair salons, they flocked to barber shops to be shorn: in New York, barbers reported lines snaking far outside their doors as 2,000 women a day clamored to be fashionable.

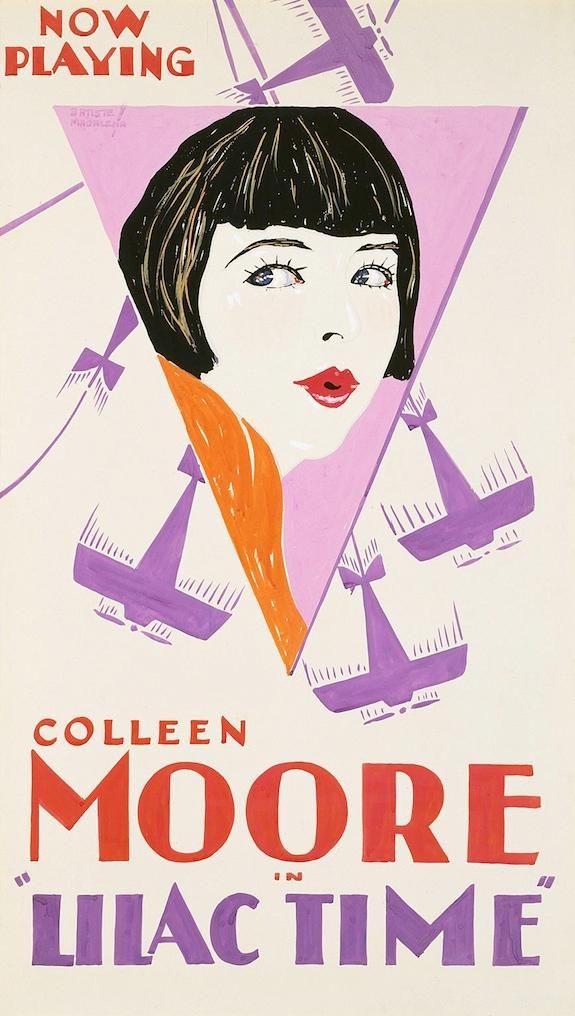

Silent film stars, America’s new cultural icons of the 1920s, helped feed the rage for chopped hair. Three stars became particular icons of the flapper look: Colleen Moore is credited with helping to define the look in her 1923 film Flaming Youth; by 1927 she was said to be America’s top box office attraction, making $12,500 a week. Clara Bow was another bobbed-hair screen star said to personify the Roaring Twenties: in 1927, she starred as the prototypic, uninhibited flapper in It. Louise Brooks was also credited with embodying the flapper: Her trademarks in such films as Pandora’s Box were her bobbed hair and a rebellious attitude about women’s traditional roles.

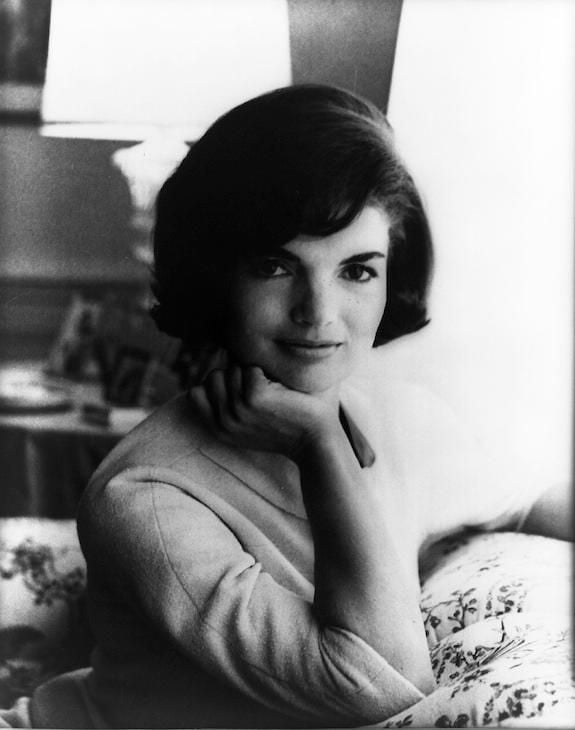

First Ladies Lou Hoover, Eleanor Roosevelt, Bess Truman, and Mamie Eisenhower made few headlines with their hairstyles—although it is true that Mrs. Eisenhower sported bangs. But when Jacqueline Kennedy became First Lady in 1961, the media went mad over her bouffant hairstyle.

When the Kennedys attended the Washington premiere of Irving Berlin’s new musical Mr. President in September 1962 at the National Theatre, journalist Helen Thomas wrote how “First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy—a devotee of the Parisian ‘pastiche’ hair-piece—is going to see a lot of other women wearing the glamorous superstructured evening coiffures at the premiere.” Mrs. Kennedy had adopted the bouffant look in the 1950s under the tutelage of master stylist Michel Kazan, who had an A-List salon on East 55th Street in New York. In 1960 Kazan sent three photographs of Mrs. Kennedy en bouffant to Vogue magazine, and the rage began. His protégé, Kenneth Battelle, was Mrs. Kennedy’s personal hair stylist during her years in the White House, and helped maintain “the Jackie look” of casual elegance.

In the 50 years since Mrs. Kennedy left the White House, First Lady coifs have rarely been subjected to much hoopla, so the advent of Michelle Obama’s bangs unleashed decades of pent-up excitement. In a January 17th New York Times article on “Memorable Clips,” Marisa Meltzer wrote that “Sometimes the right haircut at the right moment has the power to change lives and careers.” The Daily Herald reported that obsessive media attention was sparked only after the president himself called his wife’s bangs “the most significant event of this weekend.” One celebrity hairstylist was quoted as saying, “Bangs have always been there, but they are clearly having a moment right now,” adding that “Mrs. Obama is really being modern and fashion-forward. We haven’t had a fashion-forward first lady like this since Jackie Kennedy.”

Fashion-forward is a concept I find fascinating, both because “fashion and identity” is a topic that intrigues me as a cultural historian, and also because it entails one of my favorite sports—shopping. And when it comes to the corollary topic “bobbed hair and bangs,” I feel totally in-the-moment: last summer, I asked my hairstylist to give me a “duck-tail bob.” He is Turkish, and I had a difficult time translating that for him until his partner explained that the word in Turkish that came closest was “chicken-butt.” His face lighted up, and he gave me a wonderful haircut. I told him I would make a great sign for his window –“Home of the World Famous Chicken-Butt Haircut.”

A regular contributor to Around the Mall, Amy Henderson covers the best of pop culture from her view at the National Portrait Gallery. She recently wrote about Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Ball and Downton Abbey.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)