Miss Piggy, My Feather Boa and A Moment to Consider Makeup’s Greasy Past

No Fools Need Apply to the Smithsonian’s Curatorial Conference On Stuff, A Sometimes Annual Scholarly Gathering on a Subject Rarely Considered

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130405110043Cosmetics_Thumb.jpg)

How better to celebrate April Fool’s Day among scholars than to parse, deconstruct, reconsider and otherwise dismantle a subject rarely considered. This year Smithsonian curators, historians and researchers assembled at the National Museum of American History to take part in the annual (well, sometimes) “Conference on Stuff.” In the past, we’ve considered the marshmallow, Jell-O, corn, crackers, peanut butter and pie. This year, our subject was grease.

I was drawn instantly by the spirit of “dedicated hilarity” and volunteered to make a presentation on “greasepaint”—a pig fat concoction originally invented as a makeup base for actors, but one that has since morphed into a cosmetic industry that grosses an estimated $170 billion dollars annually.

For those of you who missed my talk “Greasepaint Glamour,” providing both intellectual gravitas and an excuse to fluff up and wear my boa, I will share now with my adoring online fans.

The tradition of face-painting extends as far back as the advent of image creation. Ancient Egyptians rimmed their eyes with kohl—a mixture of lead, copper, burned almonds, and soot—to ward off evil spirits; they also used a type of rouge to stain their lips and cheeks—a stain made from a deadly combination of iodine and bromine that gave us the phrase, “kiss of death.”

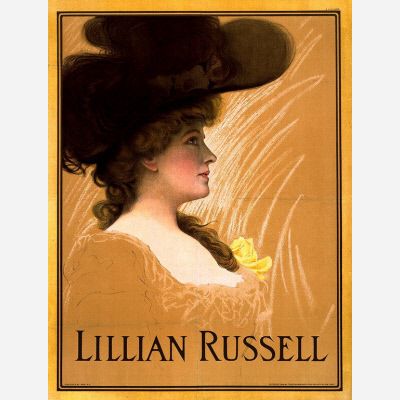

Historically, pale skin was a status symbol of upper class fashion, meant to distinguish women who spent their lives indoors rather than out in the fields. Elizabeth I coated her face with white lead and vinegar, optimistically intending to evoke a “Mask of Youth.” In the 19th century, Queen Victoria went bare-faced and declared makeup was something only worn by loose women or actors, neither of which category included Her Royal Highness. Leading actors of the American stage such as Joseph Jefferson—known for his role as Rip Van Winkle—and singer Lillian Russell wore makeup composed of an unappetizing mixture of zinc oxide, lead, mercury, and nitrate of silver.

At the turn of the 20th Century, a theatrical cosmetic based on pig fat (lard) was invented in Germany: known as “grease paint,” it was a flesh-colored paste that combined lard with zinc and ochre and gave actors a less garish, more natural appearance onstage.

With the advent of moving pictures, the demand for makeup burgeoned with the rise of the “close-up” as actors scrambled to cover flaws and enhance their most attractive facial features. Makeup also had to stand up to the powerful new lighting technology invented for filmmaking, and because black and white film stock didn’t register all colors accurately (red looked black on screen, for example), actors had to wear a green-tinged arsenic makeup that looked “natural” once projected onscreen.

Arsenic makeup’s side-effects were dangerous, but Polish immigrant Max Factor soon came to the rescue. Factor arrived in Los Angeles with his family in 1904, and by the time the movie industry began its migration from New York to “Hollywood” in the early teens, he had set up shop as a wig-maker and a makeup artist. In 1914, Factor invented “flexible greasepaint”—a makeup in a tube that revolutionized movie cosmetics because it reflected well under movie lighting. Happily, it also didn’t contain anything that could poison actors.

Flexible greasepaint was applied with a wet sponge and then “set” with powder; Factor went on to devise a “color harmony” palette that individualized makeup for such stars as Rudolph Valentino and Mary Pickford. He also coined the noun “makeup” from the verb phrase “to makeup one’s face.”

As Hollywood moved into its glamorous heyday in the 1930s, movie makeup had an enormous impact on everyday life. Women followed such fads as bleaching their hair to imitate Jean Harlow’s platinum locks, or painting their nails “Jungle Red” as Joan Crawford did in the 1939 film The Women. In 1937, Max Factor patented his “pancake makeup,” and it became so wildly successful that one-third of all American women wore it by 1940.

Cosmetics had become big business, and Factor was joined in this increasingly competitive trade by Helena Rubenstein and Elizabeth Arden. Like Factor, Rubenstein was born in Poland: she first immigrated to Australia and set up beauty salons marketing pots of her special “Krakow face cream.” Enormously successful, she soon opened salons in London, Paris, and in 1914, New York City.

Rubenstein’s Fifth Avenue salon was mere blocks from Elizabeth Arden’s, another pioneering figure in cosmetics who came to New York from rural Canada in 1907. Arden worked at a beauty salon at Fifth Avenue before opening her own salon on Fifth Avenue and 42d Street. Fiercely competitive, the two would battle royally over what a PBS documentary termed “The Powder & The Glory” for the next half century.

As I wrapped up my contribution to the Stuff Conference, I gave the final words on makeup to one of my oracles—Miss Piggy. Curator of entertainment Dwight Blocker Bowers, himself, is a fan of the grand dame of pork and before the conference we had mused together on what Miss Piggy might offer on the subject of pig-fat makeup. No fool is that pig. “If you’re going to slap lipstick on a pig,” she would likely intone, “make very sure it’s not a relative.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)