Bringing the Dazzle Back to the Blockbuster Exhibit

Casting aside today’s fondness for the understated, a curator ponders the importance of “the wow factor”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130529110059Thumb.jpg)

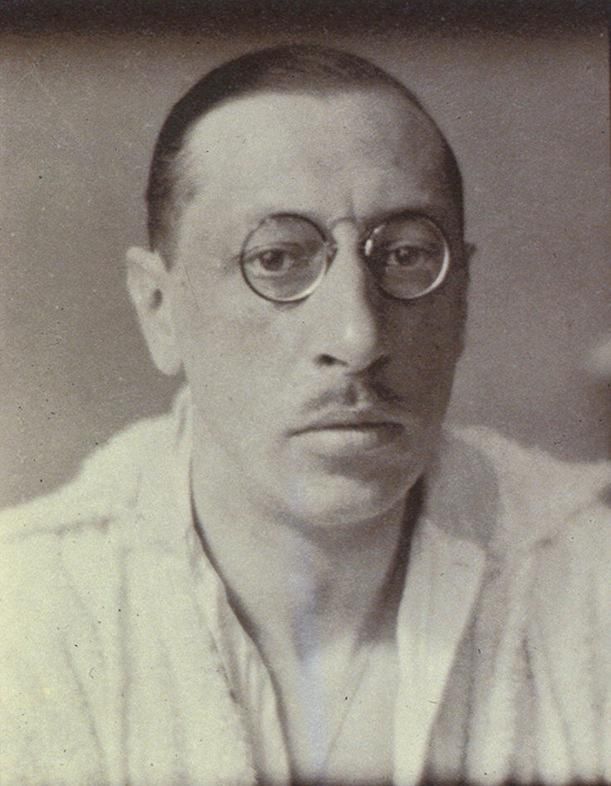

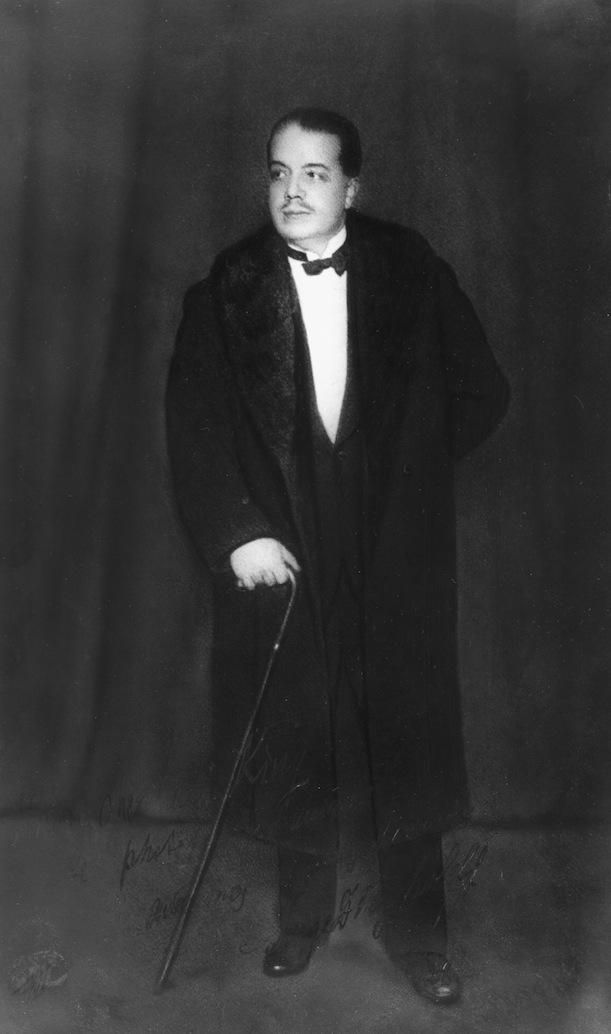

Listen carefully for a distant rumble: 100 years ago, on May 29, 1913, the shock of the new exploded in a Paris theater when Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes performed Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. The bedecked and bejeweled audience at the Theatre des Champs-Elysees erupted at the folk-ish dancing and discordant music that confronted them. Instead of the grace and tradition of such ballets as Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, Spring’s disjointed choreography and Russian pagan setting launched a chorus of boos that turned into brawls: What was all that foot stomping about? Where were the tutus of tradition? To the audience’s surprise and consternation, “Modernism” had just arrived with a giant cymbal crash.

Serge Diaghilev and Igor Stravinsky intended to use this performance as a proclamation of Modernism—a spectacle aimed at bursting through traditional boundaries in art, music and dance to present something totally new and innovative. The idea of dance-as-spectacle is something that has intrigued me, as I’ve organized a Portrait Gallery exhibition on dance in America, opening October 4. Without fomenting riots, spectacle has played a defining role in dance from Ziegfeld’s Follies to Beyonce’s stage shows; audiences are always riveted by feathers, sequins and beautiful movement. As composer-lyricists Kander and Ebb wrote in Chicago’s “Razzle Dazzle” theme song, “Give ‘em an act with lots of flash in it/And the reaction will be passionate.”

I like to be dazzled. And as an inveterate cultural explorer, I am always on the prowl for the “wow” factor—that magical thing that makes your eyes pop. In the performing arts, it can be a show-stopping moment on stage or screen, a dancer’s magnificent leap into the ozone, or a thrilling voice that leaves you breathless. These are crystalline moments that brand your psyche forever.

Lately, I have been wowed by a couple of extraordinary performances—a concert by the Philadelphia Orchestra under their electrifying new conductor, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, and a Kennedy Center Gala performance of My Fair Lady in which Jonathan Pryce and Laura Michelle Kelly made you think they were creating the roles of Professor Higgins and Eliza for the first time.

But I have also been dazzled by a mega-exhibition that has just opened at the National Gallery of Art: “Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, 1909-1929: When Art Danced with Music.” Baz Luhrmann may have used a lot of glamour and glitz in his new 3-D version of The Great Gatsby, but the Gallery has created Diaghilev’s glittering world in a sumptuous display of the real thing—the art, music, dance and costuming that expressed the “search for the new” a century ago. As the exhibition co-curator Sarah Kennel explains, Diaghilev “never wanted to rest on his laurels. He was always innovating and redesigning.”

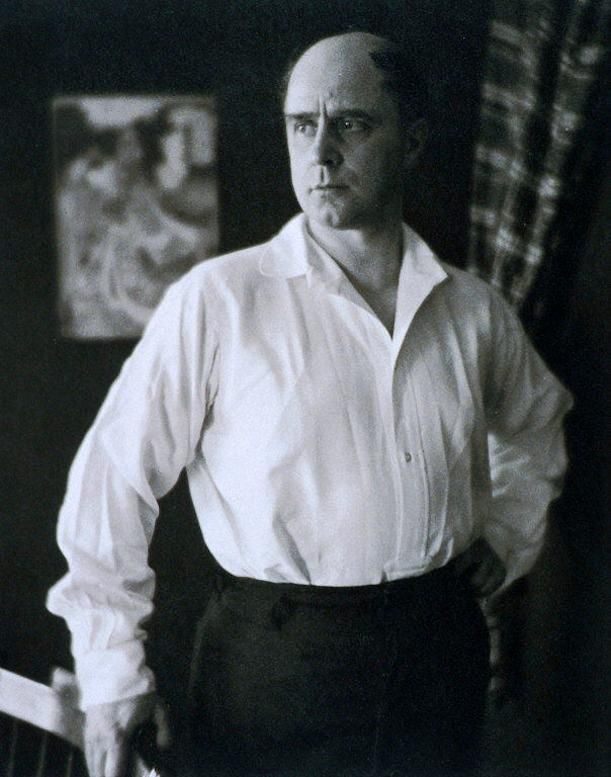

A collaboration between the National Gallery of Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum, the exhibition first opened in London in 2010. The Gallery’s exhibition is a hybrid of that show, incorporating 80 works from the V & A collection and adding about 50 new objects. “Diaghilev” showcases the astonishing artistic partnerships forged by the Russian impresario, and spotlights such composers as Stravinsky, Prokofiev and Satie, and artists like Bakst, Picasso and Matisse. Two major Diaghilev choreographers—Michel Fokine, who worked with him in the early years, and George Balanchine, who worked with the Ballets Russes at the end of Diaghilev’s life—would immigrate to the U.S.; Fokine established a ballet school in New York, and Balanchine would have an iconic impact on American dance, both on Broadway and in ballet.

Organized chronologically, the five major exhibition sections tell the story of Diaghilev’s career: “The First Seasons,” “Vaslav Nijinsky—Dancer and Choreographer,” “The Russian Avant-Garde,” “The International Avant-Garde,” and “Modernism, Neoclassicism, and Surrealism.” There is also a fascinating audio-visual component that includes rare footage of the Ballets Russes and Nijinsky, Rudolf Nureyev performing in Afternoon of a Faun, and Mikhail Baryshnikov dancing The Prodigal Son.

Thirty years ago, this fabulous exhibition would have been called a “blockbuster.” In contemporary museum parlance, that word is out of favor: blockbusters fell into the crosshairs of critical harrumphing at some point, and today’s museum world often favors a reductionist reliance on gray walls and gray carpeting rather than more flamboyant approaches. As someone who began in the blockbuster era, I find the lack of dazzle today a troubling comment on how far museums have distanced themselves from a public hungering for inspiration.

But the Diaghilev exhibition had me smiling the moment I walked into its embrace: from the beaded Boris Godunov costume Chaliapin wore in 1908 to the giant stage curtain from The Blue Train (1924), the Diaghilev show is a reminder of what exhibitions can be.

Mark Leithauser is the chief of design and senior curator at the National Gallery of Art, and here, he has created an enormous world of wow. Responsible for designing many of that museum’s landmark shows, he talked to me about how the notion of “blockbuster” is really not about size: it’s about a phenomenon. The first blockbuster, “King Tut,” had only 52 objects. When it opened at the Gallery in 1976, people stood in line for hours. Director J. Carter Brown said the show was popular because of the “sheer visual quality” and “breathtaking age” of the objects, along with the titallating sense of being on a treasure hunt. On the other hand, “Treasure Houses of Britain” in 1985 had over a thousand objects and helped connect “bigness” to the popular idea of blockbuster.

Leithauser firmly believes that an exhibition should be rooted in storytelling. In “Treasure Houses,” the story was about 500 years of collecting in Britain, but it was also about 500 years of architectural transformation in the British country house—a transformation evoked in the architectural scenes and environment created in the exhibition.

For the Diaghilev show, Leithauser said the design had to be as theatrical as the story—the installation had to create a theatrical experience that encompassed Diaghilev’s world. The truth, according to Leithauser, is that exhibitions “need to be what they are.”

The designer’s ability to set the stage so brilliantly allows visitors to understand Diaghilev’s artistic collaborations both intellectually and viscerally. Leithauser is a showman who appreciates spectacle: thumbs up for razzle dazzle!

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)