Hawaiian Musician Dennis Kamakahi Donates His Guitar

Slack Key guitar music sounds new notes for history of cowboys and the West in ceremony honoring the Hawaiian composer

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130507100057Kamakahi_Thumb.jpg)

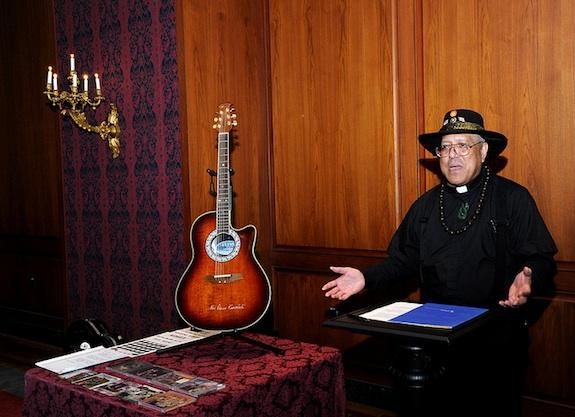

With his quiet dignity and self-assurance, leadership becomes Slack Key guitarist Reverend Dennis Kamakahi. Whether leading a cultural renaissance in his home state or a day of recognition at the Smithsonian, the Grammy-award winning composer, recording artist and Episcopalian minister exudes a presence as solid and beautiful as the music he composes and performs. Kamakahi was a member of the folk music group “The Sons of Hawaii” from 1974 to 1992 and his music was featured in the award-winning 2011 George Clooney film, The Descendants.

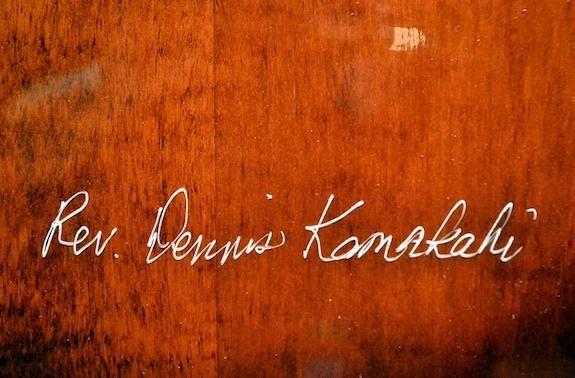

Kamakahi’s achievements as an Hawaiian folk musician and cultural historian recently found a welcome spotlight as curators at the National Museum of American History accepted his 6-string guitar, albums, sheet music and personal photographs as part of the museum’s music and history collections, a first for a modern Hawaiian composer.

A representative from the office of Congresswoman Colleen Hanabusa (D-HI) read a message praising Kamakahi as “one of the finest musicians Hawaii has ever known.”

“Through your humility, grace and love for others,” she said, “you have positively influenced so many and have represented Hawaii with dignity.”

“This is an experience, to be alive at a time you can donate something and pique the curiosity of people,” Kamakahi, told an audience of well wishers. He then used the donated guitar to play and sing songs with stories and melodies as exotic and mysterious as his state.

Kamakahi’s role as cultural ambassador is as much family mantle as professional choice. His grandfather and father were guitarists. His father played trombone in the Hawaiian Royal Band and jazz with his mentor James “Trummy” Young, trombonist with the Louis Armstrong All Stars. Hawaiian culture dictated that the eldest grandchild ”be given” to the grandparent of the same gender to mentor as guardian of the cultural heritage.

Music is in Kamakahi’s blood and his story is a fascinating one. His goal to become a classical music conductor was abandoned after a music theory teacher encouraged him to “to go back to your roots, to Hawaiian music.” In 1973, Eddie Kamae, ukelele virtuoso and co-founder of the Sons of Hawaii, invited the 19-year-old Kamakahi to join the group.

Now “we’re the last two left,” he says of the legendary band. “He’s the oldest. I’m the baby. You are what your teachers are.”

That makes Kamakahi a cultural activist, who along with Kamae, ushered in Hawaii’s cultural renaissance of the 1970s, helping to lift stigmas that had repressed Hawaii’s indigenous music and traditions for decades. Slack Key guitar music, predating ukelele music, rose like a Phoenix from cultural ashes.

Slack Key music history is steeped in the lore of the Vaqueros, Spanish and Mexican cowboys who developed cattle ranching as a business and culture in the American Southwest and West. Vaqueros were brought to Hawaii to tame an overpopulation of cattle and taught Hawaiians to become cowboys or Paniolos. They also brought guitars, trading tunes and songs around camp fires. When the Vaqueros left, the guitars remained, adopted by Paniolos who invented their own tuning—slack key—to accommodate Hawaiian music.

“It was mostly tuned to the voice,” Kamakahi explains of the style. “The high falsetto style of singing emerged because of .” Every tuning has a nickname. Families guarded tunings so closely they became family secrets. While the term Paniolo is used generically, today, to mean cowboy, it was originally reserved only for students of the Vaqueros, says Kamakahi. It’s a ”high title” going back to those days. Descendants of the original Vaqueros still live on the Big Island of Hawaii. And Kamakahi’s songs herald their histories along with those of Hawaii’s culture, religions, landscape, heroes and traditions.

“I write for story telling,” he says of his music. Hula, considered only a dance form by most mainlanders, is actually a form of storytelling that presents Hawaiian music and narrative through motion. Koke’e, a Kamakahi tune that became a Hula standard, was composed on the guitar donated to the Smithsonian.

“Original slack key music used maybe two chords,” he says. Two stories demonstrate the music’s influence and progression over the years.

Kamakahi counts the late legendary blues singer/composer Muddy Waters as a friend who used the Delta G slack key tuning throughout his career. He used to ask me, ‘Why don’t I sound like you when I play?’ I told him it’s because you don’t live in Hawaii.”

The 2011 film The Descendants, starring George Clooney, became the first feature length movie offering a full slack key music score. Kamakahi’s tune Ulili E performed with son David was featured in the film and in promotions. He said the power of the music and Clooney’s insistence on cultural authenticity won over the director after he and others invited them to a jam session at a local club.

“You can sing Hawaiian songs, but if you don’t know what you’re singing about (culturally) it’s not Hawaiian.”

While in DC he turned 60. Alumni and friends of the National Capital Region Chapter of the University of Hawai’i Alumni Association celebrated with a feast of Hula, food, music, and fundraising to support student interns. Kamakahi says he’ll still perform but wants to focus on educating others in and outside of Hawaii about the region’s history, music and culture.

He marvels that Slack Key has loyal fans as far away as Russia, Finland, France and South Africa. Exposure from The Descendants generated mail from around the world. Yet he’s concerned about the music’s future in Hawaii.

“It’s a sad time for Hawaiian music. It’s an exported music now,” he says. “It used to be in Waikiki,” a staple of tourism where musicians like Don Ho developed careers playing music lounges. That changed in the 1980s when hotel general managers recruited from outside Hawaii cut costs by replacing live music with karaoke. “Musicians like me had to go to the mainland,” says Kamakahi.

His hopes for young Hawaiian musicians is that promoting the culture will support its survival and evolution.

“Most people in Hawaii don’t know what the Smithsonian is,” he says. But Kamakahi knows the recognition validates his artistry and his culture. “I hope the Smithsonian recognition will place focus on the music back home. This honor will outlast me because it’s not only for me. It’s for those who came before me and for those who come after me.

“I tell young musicians you need to travel the world so your music will affect others, and theirs yours. Music is a communicator. It breaks down barriers. Music is the universal language that brings us together.”

He explains with an anecdote.

“I was playing at the Vancouver Music Festival and played with a West African band whose rhythms,” rooted in the blues “we hear every day in Hawaii. The bass player was in nirvana that we knew their rhythms.

“Rhythm is everywhere. Your heartbeat is the first rhythm you hear. The heartbeat is the first thing that connects you to life,” he says smiling broadly. “That’s why we’re all musical. We have a heartbeat.”

Hear from the Slack Key legend himself in an episode of the American History Museum’s podcast, History Explorer.