Poetry Matters: A Lifelong Conversation in Letters and Verse

For Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Bishop, a friendship between two poets left a beautiful written record

![]()

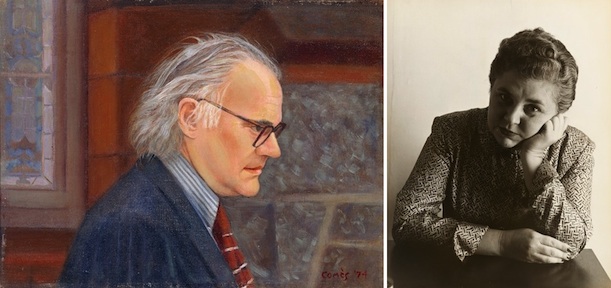

Friends Lowell and Bishop. Left: Robert Traill Lowell, (1917 -1977) by Marcella Comès Winslow (1905 – 2000) Oil on canvas Right: Elizabeth Bishop (1911–1979) by Rollie McKenna (1918–2003) Gelatin silver print, 1951. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

Historian David Ward from the National Portrait Gallery last wrote about baseball and poetry.

One of the great modern American literary friendships was between the poets Robert Lowell (1917-1977) and Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979). They met in the late 1940s and remained friends, despite some turmoil, until Lowell’s death in 1977. Bishop only survived him by two years, passing away suddenly on the day she was to give a rare public reading at Harvard University. Rare, because Bishop was very shy, especially when it came to crowds, unlike Lowell who was voluble, more than a little manic, and quite the great man of American letters.

Despite, or perhaps because of, their contrasting temperaments they bonded over poetry. It was a literary friendship in two senses: they were both fiercely committed to their craft and it was a relationship that was conducted almost entirely by mail. They were rarely in the same part of the world at the same time, not least because Bishop spent almost two decades in Brazil, living with her partner Lota de Macedo Soares. So the friends grew close by writing letters to bridge the physical distance between them.

Both Lowell and Bishop were extraordinary correspondents. Does anyone write letters anymore? But Lowell and Bishop were among the last of the generations that considered letter writing an art form. Composing experiences and thoughts in a way that was coherent and reflective, Lowell and Bishop viewed letters as minor works of art, as well as a way to keep the mind alert to writing poetry. In the lives of strong writers, one is always struck by the sheer quantity of writing that they do, and letters form the bulk of this writing. Both Lowell and Bishop were remarkable correspondents both with each other and with others. But their correspondence is sufficiently important that it has been collected in the 2008 volume Words in Air: The Complete Correspondence Between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell, edited by Thomas Trevisano and Saskia Hamilton.

The title is taken from an affectionate poem that Lowell wrote (and rewrote. .. and then rewrote again!) for Bishop in which he characterized her methods of composing poems. And this is the other great thing about Bishop and Lowell: they wrote poems in response to each other. Their letters were private communications but the poems were a public dialogue carried out in counterpoint. For instance, from Brazil Bishop dedicated a poem to Lowell called it “The Armadillo.” It begins with a beautiful image of a popular religious celebration, a mingling of the secular and the sacred:

This is the time of year

when almost every night

the frail, illegal fire balloons appear.

Climbing the mountain height,

rising toward a saint

still honored in these parts,

the paper chambers flush and fill with light

that comes and goes, like hearts.

It’s impossible not to imagine that in that image of the paper filling with light, “like hearts,” Bishop was referring to letter-writing. But the fire balloons can be dangerous, and when they fall to earth they flare into brushfires that disturb the animals: “Hastily, all alone,/a glistening armadillo left the scene/rose flecked, head down. . . “ Are these fires a warning not to get too close? Bishop and Lowell had quarreled in their letters about Lowell’s use of quotations and personal details in his poems without having asked for permission. Exposed to the public, private correspondence could detonate, injuring innocent bystanders Bishop could be saying.

Lowell responded to Bishop’s armadillo with a poem called “Skunk Hour” set in Castine, Maine, where he summered. Society is all unstable: “The season’s ill—we’ve lost our summer millionaire. . .” Half way through Lowell turns on himself. Watching the cars in Lover’s Lane: “My mind’s not right. . . .I myself am hell;/nobody’s here—//only skunks, that search in the moonlight for a bite to eat.” Lowell was frequently hospitalized throughout his life with mental illness and you can hear the desperate sense of holding on as everything seems to be falling apart in this verse. “Skunk Hour” ends with an image of obdurate resistance that the poet fears he cannot share: the mother skunk, foraging in a garbage can, “drops her ostrich tail,/and will not scare.”

The title for their collected correspondence comes from Lowell’s poem for Bishop that includes the lines: “Do/you still hang your words in the air, ten years/unfinished, glued to your notice board, with gaps or empties for the unimaginable phrase—unerring Muse who makes the casual perfect?”

Unlike the voluble Lowell, Bishop was a very deliberate writer and Lowell is referring to her habit of pinning up the sheets of a work in progress and making it, essentially, part of the furniture of her life. She mulled over the work, considering and reworking the poem until she was finally satisfied with it; reportedly she worked on her well known poem “The Moose” for nearly two decades before publishing it.

Lowell was just the opposite, not least because he revised and rewrote poems even after he had published them, causing a great deal of trouble and confusion for his editors in establishing an accurate final text. Indeed, he fiddled continually with his poem to Bishop, turning it into something rather more formal and monumental in the final version.

Lowell never read Bishop’s response: it came in a memorial poem called “North Haven,” a poem like “Skunk Hour” about the seacoast. It’s a lovely tribute, full of rueful knowledge of Lowell’s character: “(‘Fun’—it always seemed leave you at a loss. . .)” and ends with

You left North Haven, anchored in its rock,

afloat in mystic blue. . .And now – you’ve left

for good. You can’t derange, or rearrange,

your poems again. (But the sparrows can their song.)

The words won’t change again. Sad friend, you cannot change.

It’s uneasy to cite sadness or depression as a cause of artistic creativity; most depressives aren’t great poets. Both Lowell and Bishop were sad in their various ways. Poetry, Robert Frost wrote, provides a “momentary stay against confusion.” But that’s not all it does. Indeed, in the case of Bishop and Lowell it could be argued that it was the letters that provided a structure of meaning and feeling for both poets that helped them make sense and order their experience. The poems themselves are something else entirely: expressions of feeling and self-knowledge that appear as art.