Picture-Perfect Bonsai

In a new book, botanical photographer Jonathan Singer focuses his lens on the potted plants

![]()

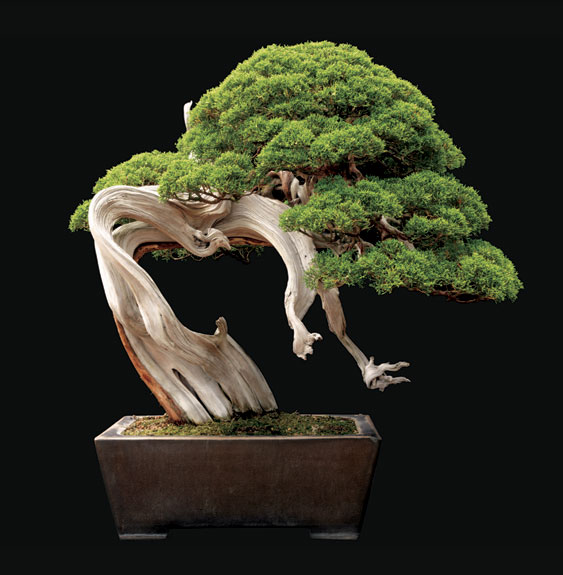

A 250-year-old Sargent juniper from Saitama City, Japan. The plant stands 28 inches tall. Courtesy of Jonathan Singer.

Three years ago, I was introduced to Jonathan Singer, a podiatrist from Bayonne, New Jersey, who was making quite a splash in the world of botanical photography. He had just published Botanica Magnifica, a five-volume book with 250 stunning photographs of orchids and other exotic flowers on pitch-black backgrounds. Measuring an impressive two feet by three feet, the images were compiled by flower type in hand-pressed, double-elephant folios—a format not used since Audubon’s Birds of America in the 1840s.

John Kress, a Smithsonian botanist who has collected rare plant species in Thailand, Myanmar and China, said at the time, ”I have a hard time getting on my own digital camera the exact color of any plant in the field…. are as close as I have ever seen. They look exactly like the real thing.”

Enamored by the photographer’s very first prints, Kress invited Singer to the National Museum of Natural History’s research greenhouse in Suitland, Maryland. There, Kress hand-selected some of the most visually interesting specimens for Singer to shoot with his color-perfect Hasselblad digital camera.

For his latest project, Singer takes on a new subject: bonsai. Using the same technique, he has photographed some 300 bonsai trees from collections around the world and presented them in his new large-format book, Fine Bonsai.

Bonsai, meaning “to plant in a tray,” is a tradition that originated in China about 2,000 years ago and later traveled to Japan. To cultivate a bonsai, a horticulture artist starts with a cutting, seedling or small specimen of a woody-stemmed tree or shrub and then trains the plant to grow in a certain way, by pruning leaves and wiring branches into a desired shape. The goal is to create a miniature tree that looks natural, despite the artist’s constant manipulations.

“To some people these miniature trees, which have been twisted, trained and dwarfed for their entire lives, may seem grotesque,” writes Kress, in an essay in the book. But, to others, they are beautiful, living sculptures.

Measuring 22 inches tall, this 40-year-old Koto Hime Japanese Maple can be found at the International Bonsai Arboretum in Rochester, New York. Courtesy of Jonathan Singer.

Singer was skeptical of his subject at first. He knew little about bonsai. But his publisher at Abbeville Press encouraged him to photograph the dwarfed plants.

His first shoot, at the U.S. National Arboretum in Washington, D.C., presented some challenges. “I found it extremely difficult to shoot them,” says Singer. “Bonsai are put in a certain location, and they can’t be moved at all.” Behind each of the 25 or so fragile plants he shot, Singer and an assistant set up a black background. “We did not touch one of them,” he says.

As his style, Singer snapped a single photograph of each plant. “I take the trigger, I pull it once and it is over,” he says, confidently.

Once he saw the resulting photographs, Singer warmed to bonsai. “They are rather beautiful in their own way,” he says.

The photographer was fortunate enough to get access to several public and private bonsai collections. In the United States, he visited the Kennett Collection in Pennsylvania, the Pacific Rim Bonsai Collection in Washington, D.C., the Golden State Bonsai Federation Collection in San Marino, California, and the International Bonsai Arboretum in Rochester, New York. Then, in Japan, he was able to photograph bonsai at the Shunka-en Bonsai Museum in Tokyo, the S-Cube Uchiku-Tei Bonsai Garden in Hanyu and the crown jewel of bonsai collections, the Omiya Bonsai Village of Saitama.

This 40-year-old Sargent juniper from the Pacific Rim Bonsai Collection in Washington, D.C., resembles a mature forest. However, the plant measures only 35 inches tall. Courtesy of Jonathan Singer.

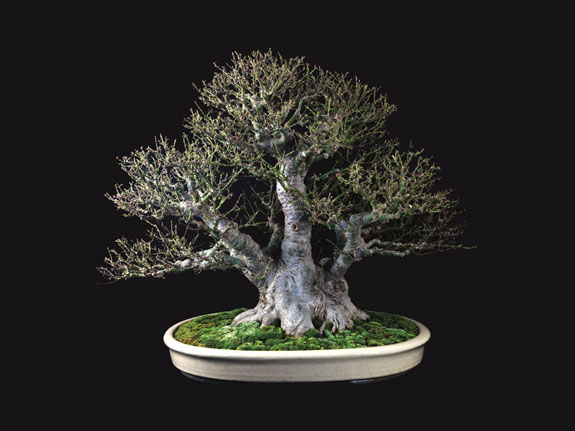

Singer selected bonsai based on features that caught his eye—a bizarre root here, some colorful foliage and interesting bark there. He also took suggestions from bonsai artists. In the end, Fine Bonsai became a photographic collection of some of the most masterful bonsai—from five years old to 800—alive today.

“Each one is a result of somebody who has planned,” says Singer. An artist sets out with a vision for a bonsai, and that vision is ultimately executed by several generations of artists. When one artist dies, another takes over. “That’s the allure for me,” adds Singer.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)