Slice of Life: Artistic Cross Sections of the Human Body

Artist Lisa Nilsson creates elaborate anatomical illustrations from thin strips of paper

![]()

Lisa Nilsson was on an antiquing trip three or four years ago when a gilt crucifix caught her eye. The cross was crafted using a Renaissance-era technique called quilling, where thin paper is rolled to form different shapes and patterns.

“I thought it was really beautiful, so I made a couple of small, abstract gilt pieces,” says Nilsson, an artist based in North Adams, Massachusetts. She incorporated these first forays in quilling into her mixed media assemblages.

Almost serendipitously, as Nilsson was teaching herself to mold and shape the strips of Japanese mulberry paper, a friend sent her a century-old, hand-colored photograph of a cross section of a human torso from a French medical book. “I have always been interested in scientific and biological imagery,” says the artist. “This image was really inspiring.”

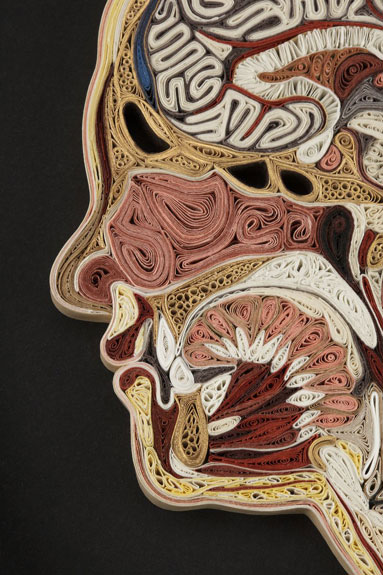

In the cross section, Nilsson saw many of the shapes that she had already been coiling and building. The quilling technique, she thought, with its “squeezing shapes into a cavity,” certainly lent itself to her subject matter. She could make tiny tubes and squish them together to fill the many different spaces in the body—lungs, vertebrae, pelvic bones and muscles.

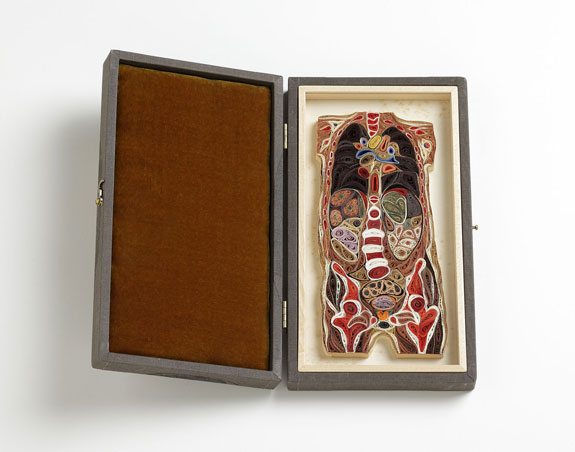

Her first anatomical paper sculpture, Female Torso (shown at top), is a near-direct translation of the French medical image.

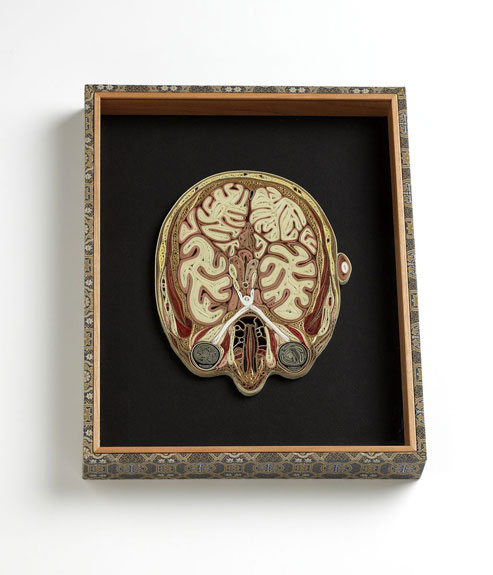

Nilsson went on to create an entire Tissue Series, which offers artistic slices, literally, of male and female bodies: a cross section of a head at eye level (above), another of a chest just above a man’s arm pits (below) and one of an abdomen at navel height, to name a few.

Nilsson began exhibiting her paper sculptures at galleries and museums. “The two words that I heard most often to describe the work were ‘beautiful,’ which is always nice to hear, and…’creepy,’ ” she said in a talk at TEDMED, an annual conference focusing on health and medicine. The artist admits that she never found the project disturbing. “I was so enthralled with the aesthetic possibilities I saw in cross sections, I had kind of overlooked the idea that viewing the body in this sort of ‘slice of deli meat’ fashion could be a bit unsettling to people,” she said.

Viewers come in close, at first, she says. “They would see the piece as an intriguing handmade object and put their noses up to the glass and enjoy the subtle surprise that it is made of paper,” she says, in the TEDMED lecture. Up close, a portion of the lacy, intricate sculpture appears abstract. “Then, people would typically back away, and they would be curious about what region of the body they were looking at….They would usually start to identify familiar anatomical landmarks.” The heart, perhaps, or the ribcage.

When making a paper sculpture, Nilsson starts with medical images, often culled from the Visible Human Project, a National Library of Medicine initiative that collected anatomical images from one male and one female cadaver. She usually consults illustrations of specific parts of the body in medical textbooks as well, to better understand what it is she is seeing in the Visible Human cross sections. “My background is in illustration”—she has a degree from the Rhode Island School of Design—”so I am used to combining sources and just being resourceful in getting all of the visual information I need to say what I want to say,” she says.

Nilsson creates a composite image from these sources and adheres it to a base of styrofoam insulation. The two-dimensional image serves as a guide for her three-dimensional paper sculpture; she quills in between the lines, much like one colors in a coloring book.

“I often start in the center and work out,” says Nilsson. She builds a small quilling unit, pins it to the styrofoam base and then glues it to its neighbor. “It is almost like putting a puzzle together, where each new piece is connected to its predecessor,” she adds. Working in this “tweezery” technique, as the artist calls it, requires some serious patience. A sculpture can take anywhere from two weeks to two months to complete. But, Nilsson says, “It is so addictive. It is really neat to see it grow and fill in.”

There is a basic vocabulary of shapes in quilling. “I have really tried to push that,” says Nilsson. “One of the things I don’t like about a lot of quilling that I see is that the mark is too repetitious. It is curlicue, curlicue, curlicue. I really try to mix that up.” Follow the individual strands of paper in one of her sculptures and you will see tubes, spirals, crinkled fans and teardrops.

When the sculpture is finished, and all the pins have migrated to the periphery, Nilsson paints the back with a bookbinder’s glue to reinforce it. She displays her cross sections in velvet-lined shadow boxes. “I really like them to read as objects rather than images. I like the trompe-l’oeil effect, that you think you might be actually looking at a 1/4-inch slice of a body,” says Nilsson. “The box, to me, suggests object and frame would suggest an image. The decorative boxes also say that this is a precious object.”

Many medical professionals have taken an interest in Nilsson’s work. “It feels like an homage, I think, to them, rather than that I am trivializing something that they do that is so much more important,” she says, with a humble laugh. Doctors have sent her images, and anatomists have invited her to their labs. She even has a new pen pal—a dissector for Gunther von Hagens’ Body Worlds, a touring (and somewhat startling!) exhibition of preserved human bodies.

The connections Nilsson has made in the medical community have proven to be quite helpful. “Where does this particular anatomical structure end and where does the next one begin? Sometimes it is not all that clear-cut,” says the artist. As she works, questions inevitably arise, and she seeks out anatomists for answers. “Sometimes I want to know what is a general anatomical structure and what is an idiosyncrasy of the particular individual I am looking at. Rib cages. How much variance in shape is there? Am I overemphasizing this ? I am always wondering, am I seeing this accurately? Am I reading this right?”

Ultimately, Nilsson hopes that her works familiarize people with the internal landscape of the human body—the “basic lay of the land,” she says. “Everything is tidily squished in there in this package that is graphically beautiful and also highly functional,” she adds. “To me, the shapes are endlessly interesting. There is just the right amount of symmetry and asymmetry.”

Two of Nilsson’s latest pieces will be featured in “Teaching the Body: Artistic Anatomy in the American Academy, from Copley, Rimmer and Eakins to Contemporary Artists,” a three-month exhibition opening at the Boston University Art Gallery at the Stone Gallery on January 31.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)