Before and After: America’s Environmental History

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0c/ea/0cea6fef-ea09-446d-a8dd-349d061a55fa/aspen-600.jpg)

![]()

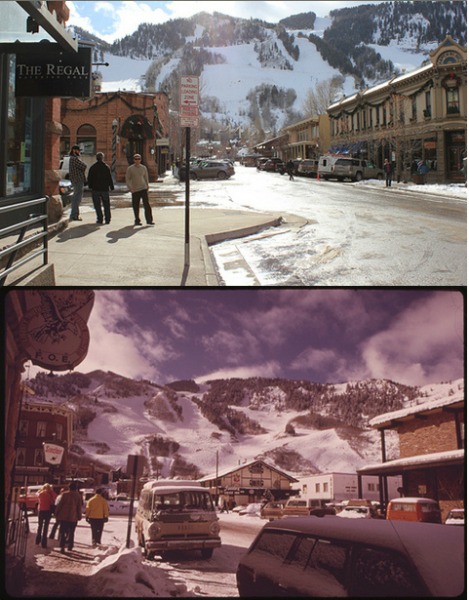

A difference of nearly four decades: at top, a ski area in Aspen, Colorado last year, captured by Ron Hoffman; at bottom, the same location in 1974, shot by Dustin Wesley. Credit: US EPA

In 1971, about 70 photographers, commissioned by the newly formed Environmental Protection Agency, set out to document the American landscape on just 40 rolls of film each. They trudged through coal mines and landfills, traversed deserts and farms and discovered big cities’ small corridors. The end result was DOCUMERICA, a collection of more than 15,000 shots capturing the country’s environmental problems—from water and air pollution to industrial health hazards—over six years.

Decades later, a new generation of photographers is collecting ”after” pictures. In the past two years, the EPA has collected more than 2,000 photos, all of which loosely depict the environment. The State of the Environment Photography Project, as the effort is called, asks photographers to take shots that match scenes from DOCUMERICA, to show how the landscape has changed since the 1970s. It also asks photographers to capture new or different environmental issues, with the idea that these modern scenes could in turn be re-photographed in the distant future; the EPA has released several of these shots for this year’s Earth Day. The project will accept submissions through the end of 2013.

The EPA explains that DOCUMERICA became a baseline for America’s environmental history, and that tracking change is key for public eco-consciousness.

Both images, taken by Michael Philip Manheim, show a section of East Boston in the 1970s and present day. Decades ago, rows of triple-deckers lined the streets of the neighborhood. Today, only one remains, the sole survivor of nearby airport expansion. Credit: Michael Philip Manheim/US EPA

There’s more to capturing environmental issues on camera than shooting smoke stacks and nuclear plants. The most effective way to convey them is to photograph people, says Michael Philip Manheim. Manheim, one of DOCUMERICA’s photographers, documented noise pollution in East Boston in the ’70s, portraying the deterioration of a close-knit community as nearby Logan Airport expanded its runways. That’s what made DOCUMERICA strike a chord with the public years ago, providing closeups of miners suffering from black lung and kids playing basketball in cramped housing developments.

“Meet the affected people, let them know how you care, find out what impacts them the most,” advises Manheim about matching his photos today. He still has the cameras he used for his assignment, which he treats as “sculptures” that stay hidden in closets. “After that, it’s time to energize a camera, and not by posing pictures but by reacting candidly to what is going on in the lives of your subjects.”

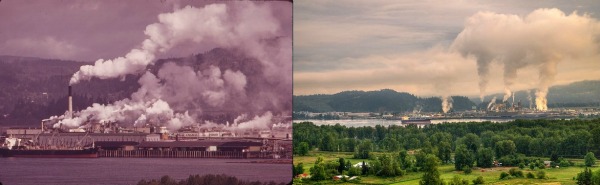

At left, DOCUMERICA photographer David Falconer’s shot of the Weyerhaeuser Paper Mills and Reynolds Metal Plant along the Columbia River in Washington State. At right, Craig Leaper’s re-creation. Credit: US EPA

Though some landscapes remain the same, Manheim says what’s changed since DOCUMERICA is the level of awareness of environmental issues. The photographer attributes this increase to the rapid spread of digital information, a visual online petition that he says Bostonians could have used to fight back in the 1970s.

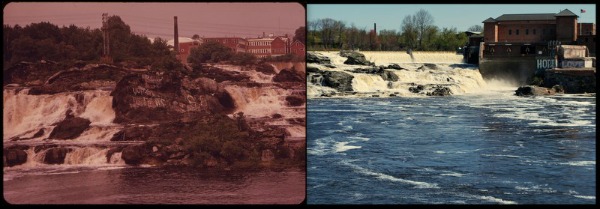

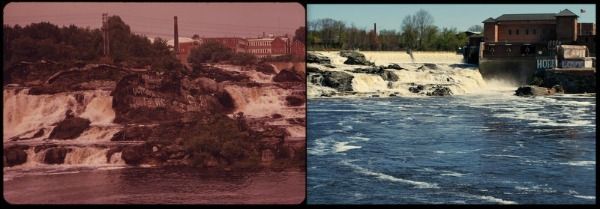

At left, the Great Falls of Maine’s Androscoggin River, with the city of Lewiston in the background, captured by Charles Steinhacker in 1973. At right, a replication of the same scene by Munroe Graham. Credit: US EPA

The “now” and “then” photos show varying degrees of change when placed side-by-side, funky fashions and clunky cars aside. Clumps of unnatural foam continue to bob along polluted waters near industrial buildings, but considerably less smog hangs in the air of some urban cities. In an “after” shot of a section of John Day Dam between Oregon and Washington State, a set of wind turbines appear on the background terrain.

At left, the John Day Dam viewed from the Washington side of the Columbia River, photographed by David Falconer in 1973. At right, a similar view, including wind turbines along the ridge, taken by Scott Butner in 2012. Credit: US EPA

The ease of digital photography will help propel the current iteration of an environmental snapshot, Manheim says. When shooting on film, photographers can’t know right away whether they’ve taken “the shot.” Digital allows them to examine the first few shots of a scene, and then find better ways to convey its details.

“You don’t stand around, waiting for something to happen. You exert mental and physical energy,” Manheim says. For anyone wanting to participate in the State of the Environment project, the photographer has some advice: “Set the scene in your coverage, and then you go for the ‘good stuff.’ You get close, closer, closest. You move in to explore and find the epitomizing image, close and meaningful, that symbolizes the situation.”

In the 1970s, Manheim got to know the people who lived in the colorful triple-decker row houses lining Neptune Road in East Boston. Planes soared overhead nearly every three minutes, prompting the nearby residents to cover their ears from the deafening roar of the engines. He captured one of these low-flying planes in a photograph, shown above. In 2012, Manheim returned to the site to document it yet again. The “then” and “now” pairing tells a story that has played out over decades. Eventually, the adjacent airport built runways flush to the streets’ backyards and driveways, and today, only one home remains.

South Boston’s Moakley Park. At left, Ernst Halberstadt smog-heavy shot in 1973; at right, Roger Archibald’s 2012 take. Once a muralist for the Works Progress Administration (WPA), Halberstadt documented city life in Boston for DOCUMERICA. Credit: US EPA

In 1971, about 70 photographers, commissioned by the newly formed Environmental Protection Agency, set out to document the American landscape on just 40 rolls of film each. They trudged through coal mines and landfills, traversed deserts and farms and discovered big cities’ small corridors. The end result was DOCUMERICA, a collection of more than 15,000 shots capturing the country’s environmental problems—from water and air pollution to industrial health hazards—over six years.

Decades later, a new generation of photographers is collecting ”after” pictures. In the past two years, the EPA has collected more than 2,000 photos, all of which loosely depict the environment. The State of the Environment Photography Project, as the effort is called, asks photographers to take shots that match scenes from DOCUMERICA, to show how the landscape has changed since the 1970s. It also asks photographers to capture new or different environmental issues, with the idea that these modern scenes could in turn be re-photographed in the distant future; the EPA has released several of these shots for this year’s Earth Day. The project will accept submissions through the end of 2013.

The EPA explains that DOCUMERICA became a baseline for America’s environmental history, and that tracking change is key for public eco-consciousness.

There’s more to capturing environmental issues on camera than shooting smoke stacks and nuclear plants. The most effective way to convey them is to photograph people, says Michael Philip Manheim. Manheim, one of DOCUMERICA’s photographers, documented noise pollution in East Boston in the ’70s, portraying the deterioration of a close-knit community as nearby Logan Airport expanded its runways. That’s what made DOCUMERICA strike a chord with the public years ago, providing closeups of miners suffering from black lung and kids playing basketball in cramped housing developments.

“Meet the affected people, let them know how you care, find out what impacts them the most,” advises Manheim about matching his photos today. He still has the cameras he used for his assignment, which he treats as “sculptures” that stay hidden in closets. “After that, it’s time to energize a camera, and not by posing pictures but by reacting candidly to what is going on in the lives of your subjects.”

Though some landscapes remain the same, Manheim says what’s changed since DOCUMERICA is the level of awareness of environmental issues. The photographer attributes this increase to the rapid spread of digital information, a visual online petition that he says Bostonians could have used to fight back in the 1970s.

The “now” and “then” photos show varying degrees of change when placed side-by-side, funky fashions and clunky cars aside. Clumps of unnatural foam continue to bob along polluted waters near industrial buildings, but considerably less smog hangs in the air of some urban cities. In an “after” shot of a section of John Day Dam between Oregon and Washington State, a set of wind turbines appear on the background terrain.

The ease of digital photography will help propel the current iteration of an environmental snapshot, Manheim says. When shooting on film, photographers can’t know right away whether they’ve taken “the shot.” Digital allows them to examine the first few shots of a scene, and then find better ways to convey its details.

“You don’t stand around, waiting for something to happen. You exert mental and physical energy,” Manheim says. For anyone wanting to participate in the State of the Environment project, the photographer has some advice: “Set the scene in your coverage, and then you go for the ‘good stuff.’ You get close, closer, closest. You move in to explore and find the epitomizing image, close and meaningful, that symbolizes the situation.”

In the 1970s, Manheim got to know the people who lived in the colorful triple-decker row houses lining Neptune Road in East Boston. Planes soared overhead nearly every three minutes, prompting the nearby residents to cover their ears from the deafening roar of the engines. He captured one of these low-flying planes in a photograph, shown above. In 2012, Manheim returned to the site to document it yet again. The “then” and “now” pairing tells a story that has played out over decades. Eventually, the adjacent airport built runways flush to the streets’ backyards and driveways, and today, only one home remains.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/marina-koren-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/marina-koren-240.jpg)