Art Chronicles Glaciers As They Disappear

The Whatcom Museum in Bellingham, Washington, is exhibiting 75 works of art pulled from the past two centuries—all themed around ice

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20131127112018Rockwell-Kent-Resurrection-Bay-Alaska-web.jpg)

In a courtyard outside the Whatcom Museum in Bellingham, Washington, there is small piece of ice, roped off. The sight is a curious one, for sure. What is so important about this single frozen mass that it warrants special treatment?

The question is one that Barbara Matilsky, the museum’s curator of art, hopes you might ask.

The ice is a dwindling sculpture, a site-specific installation called Melting Ice by Jyoti Duwadi, that less than a month ago stood firmly, a stack of 120 ice blocks each measuring 36 by 14 by 14 inches. The artist installed the cube in timing with the opening of the museum’s latest exhibition, “Vanishing Ice: Alpine and Polar Landscapes in Art, 1775-2012,” and left it to melt—an elegy to glaciers around the world that are receding as a result of climate change.

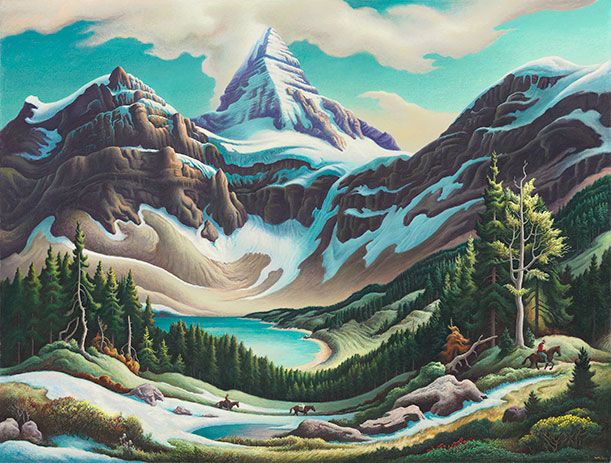

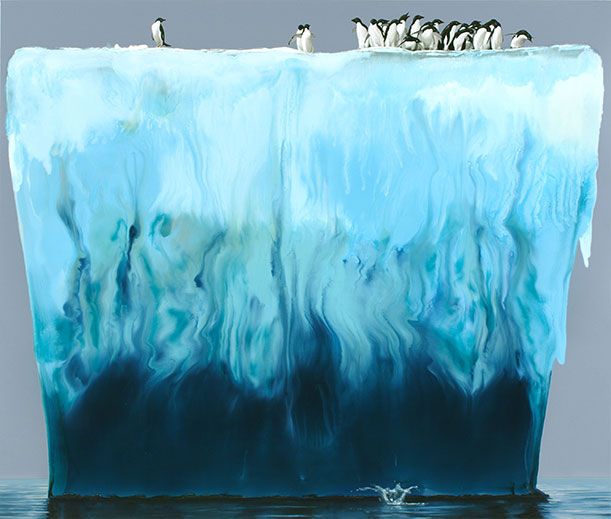

“Vanishing Ice,” on display through March 2, 2014, features 75 works by 50 international artists who have made icy landscapes their subjects in the past 200-plus years. The exhibition, in its array of various mediums, conveys the beauty of alpine and polar regions—the pristine landscapes that have inspired generations of artists—at a time when rising temperatures pose a threat to them.

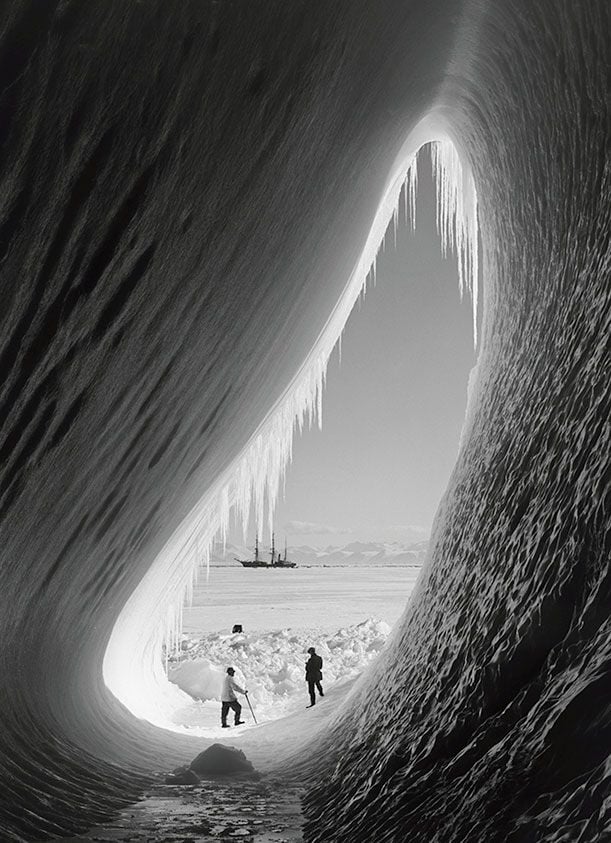

It also shows how artists and scientists have collaborated to learn what they can about these dramatically changing places. In a few pieces, a contemporary artist documents the very location that another had decades before, for the sake of comparison.

As the exhibition’s narrative tells, ice has captured the imaginations of artists for centuries. The very first known artistic depiction of a glacier dates back to 1601. It is a watercolor depicting the topography of the Rofener Glacier in Austria by a man named Abraham Jäger. But, in the 18th and 19th centuries, it became more common for artists, acting also as naturalists, to explore glaciated regions, fleeing the routine of everyday life for a jolting spiritual adventure. Their artistic renderings of these hard-to-reach locales served to educate the public, sometimes even gracing the walls of natural history museums and universities.

In the exhibition catalog, the show’s curator, Barbara Matilsky, claims that there is something sublime about these extreme places. In a sense, the snowy, glistening surfaces are ideal for reflecting our own thoughts. “Through the centuries,” she writes, “artists have demonstrated the limitless potential of alpine and polar landscapes to convey feelings, ideas and messages.”

The idea for “Vanishing Ice” actually came to Matilsky, who wrote her doctoral thesis 30 years ago on some of the earliest French artists to capture glaciers and the Northern Lights, when she began to notice a critical mass of artists working today heading off to high peaks, Antarctica and the Arctic. She drew some connections in her mind’s eye. Like their 18th, 19th and 20th century predecessors, these artists are often part of government-sponsored expeditions, rubbing shoulders with scientists. And then, as now, and their work reaches into scientific discussion as visuals that document scientific observations.

The recent art tends to illustrate the disheartening findings of climate experts. David Breashears, an American photographer and five-time climber of Mount Everest, for instance, committed himself to what he calls the Glacier Research Imaging Project. For the endeavor, he “retraced the steps of some of the world’s greatest mountain photographers. . . over the past 110 years across the Himalaya and the Tibetan Plateau.” Both his photograph West Rongbuk Glacier, taken in 2008, and Edward Oliver Wheeler’s record of the same vista, from a topographical survey of Everest in 1921, are included in the exhibition. The then-now comparison captures the glacier’s 341-foot retreat.

American James Balog approaches his timelapse photography with a similar degree of precision. His Extreme Ice Survey, also represented in the exhibition, strings together the images routinely snapped by 26 cameras aimed at more than a dozen glaciers in Greenland, Iceland, Nepal, Alaska and the western United States. The footage speeds up, for our eyes, the melting that is occurring in these regions.

“Vanishing Ice” has been four years in the making, more if you consider Matilsky’s introduction to this genre of art in the nascent stages of her career. The curator of art at the Whatcom Museum composed a wish list of paintings, prints and photographs and negotiated the loans from institutions worldwide. What resulted is an impressive body of work, including pieces from the likes of Jules Verne, Thomas Hart Benton, Ansel Adams and Alexis Rockman.

The Whatcom Museum will host the exhibition through March 2, 2014, and, from there, it will travel to the El Paso Museum of Art, where it will be on display from June 1 to August 24, 2014.

Patricia Leach, executive director of the museum, sees “Vanishing Ice” as a powerful tool. “Through the lens of art, the viewer can start thinking about the broader issue of climate change,” she says. “Believe it or not, there are still people out there who find this to be a controversial topic. We thought that this would open up the dialogue and take away the politics of it.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)