A New Meaning to Green Urban Design: Dyeing the Chicago River

The story behind how the Windy City gets its yearly watery makeover

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130315112039Green_Chicago_River_4701.jpg)

Every year on March 17, monuments around the world go green for 24 hours to celebrate St. Patrick’s day. The most famous of these temporary interventions is the dyeing of the Chicago River.

The tradition started in 1961 when water pollution controls were first enforced in the Windy City and a Chicago plumber was trying to locate a pipe that was dumping waste into the Chicago River. In order to find the waste line in question, a green dye was dumped into several waste systems to determine which one was dumping into the city’s eponymous river. It’s a simple enough idea. But at the end of the day when the plumber reported to Stephen Bailey, business manager of the Plumber’s Union, chairman of the St. Patrick’s Day parade, and consummate showman, Bailey saw the plumber’s dye-soaked jumpsuit and had an epiphany that would forever change the face of Chicago — at least for one day a year. A few phone calls later, during which he surely had to convince politicians and engineers that he was, in fact, not joking, plans were in place to dye the river green on St. Patrick’s Day using the same chemical compound that coated the plumber’s coveralls.

Although Bailey intended that the river remain green for only a single day, the process was something of an experiment and when it was first attempted in 1962, Bailey mixed 100 pounds of dye into the river with speedboats, which turned out to be a little too much and the holiday spirit was accidentally extended for an entire week. In following years, the recipe was refined and eventually perfected. Today, about 40 pounds of the dye is used.

That original dye actually has a pretty fascinating history of its own. It’s called fluorescein and was first synthesized in 1871 by Nobel Prize winning chemist Adolf von Baeyer, who also created synthetic indigo, so thank him for those sweet jeans you’re wearing.

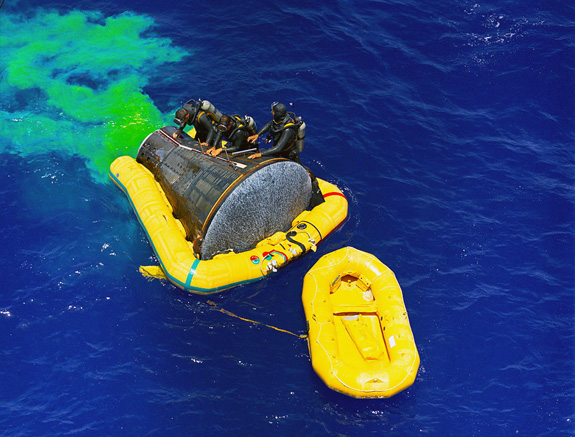

Fluorescein is a synthetic compound that turns from an orange or red to green when mixed into water and excited by sunlight. It was commonly used to trace water flows, check for leaks, and study pollution or drainage. Outside of plumbing –way outside of plumbing– fluorescein has also played an important role in the air and space industry. Not only has it been used by militaries around the world to help locate parachutists who have landed in water, but it was also famously used to help locate the Gemini IV, the first NASA mission to be supported from Mission Control in Houston, after its landing capsule crashed into the ocean more than 40 nautical miles of course due to the failure of its guidance control systems.

Although it was deemed to be safe for the river, concerned environmentalists in Chicago petitioned the local government to find a more natural replacement for the fluorescein in 1966 and as a result, a “thoroughly tested,” top-secret, vegetable-based dye is now used. When asked about the safety of the current mystery dye in 2005, Laurene von Klan, executive director of Friends of the Chicago River, told the Chicago Tribune that “It’s not the worst thing that happens to the river. When you look closely at the problem, it’s not something that needs to be our priority right now. In fact, when that becomes our most important issue, we’ll all have to celebrate because it will mean the river has improved so much. . . . Studies show for creatures who live in the river now, is probably not harmful.”

But dyeing the river was only one of Bailey’s holiday urban design schemes. He also proposed using green flood lights to dye the Wrigley Building green, but ultimately had his idea rejected. Bailey was ahead of time, a holiday visionary. In the years since his first grand infrastructural intervention, cities around the world have started transforming their buildings buildings and even entire landscapes with go green on St. Patrick’s Day: The Empire State Building, The Sydney Opera House, the London Eye, Tornoto’s CN Tower, Table Mountain in Cape Town, the Prince’s Palace in Monaco, and the list goes on.

Today, going “green” has taken on a different meaning. Thanks to an increasing interest in climate change and sustainability, the color now carries political, economic, and urban connotations. It seems fitting then that the literal “greening” of the world cities on St. Patrick’s Day began with a law designed to control and reduce pollution.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)