What Paul Robeson Said

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20110913104009Past-Imperfect-Paul-Robeson-470.jpg)

In April 1949, just as the Cold War was beginning to intensify, actor, singer and civil rights activist Paul Robeson traveled to France to attend the Soviet Union-sponsored Paris Peace Conference. After singing “Joe Hill,” the famous ballad about a Swedish-born union activist falsely accused and convicted of murder and executed in Utah in 1915, Robeson addressed the audience and began speaking extemporaneously, as he often did, about the lives of black people in the United States. Robeson’s main point was that World War III was not inevitable, as many Americans did not want war with the Soviet Union.

Before he took the stage, however, his speech had somehow already been transcribed and dispatched back to the United States by the Associated Press. By the following day, editorialists and politicians had branded Robeson a communist traitor for insinuating that black Americans would not fight in a war against the Soviet Union. Historians would later discover that Robeson had been misquoted, but the damage had been almost instantly done. And because he was out of the country, the singer was unaware of the firestorm brewing back home over the speech. It was the beginning of the end for Robeson, who would soon be declared “the Kremlin’s voice of America” by a witness at hearings by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Committee chair John Wood, a Georgia Democrat, summoned baseball great Jackie Robinson to Washington. Robinson, appearing reluctantly, denounced Robeson’s views and assured the country that the singer did not speak on behalf of black Americans. Robeson’s passport was soon revoked, and 85 of his planned concerts in the United States were canceled. Some in the press were calling for his execution. Later that summer, in civil rights-friendly Westchester County, New York, at the one concert that was not canceled, anti-communist groups and Ku Klux Klan types hurled racial epithets, attacked concertgoers with baseball bats and rocks and burned Robeson in effigy. A man who had exemplified American upward mobility had suddenly become public enemy number one. Not even the leading black spokesmen of the day, whose causes Robeson had championed at great personal cost, felt safe enough to stand by the man dubbed as the “Black Stalin” during the Red Scare of the late 1940s and ’50s.

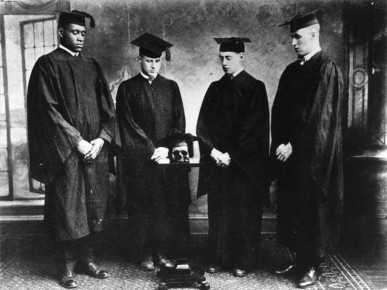

Cap and Skull society members at Rutgers University, Class of 1919. Photo: Rutgers University Archives

Paul Leroy Robeson was born in 1898, the son of a runaway slave, William Drew Robeson. He grew up in Princeton, New Jersey, where he gained fame as one of the greatest football players ever, earning back-to-back first-team All-America honors in 1917 and 1918 at Rutgers University. But Robeson was a scholar as well. A member of the Rutgers honor society, Cap and Skull, he was chosen as valedictorian of his class, and after earning his bachelor’s degree, he worked his way through Columbia Law School while playing professional football. Although he had a brief stint at a New York law firm after graduating, Robeson’s voice brought him public acclaim. Soon he was starring on Broadway, as well as on the greatest stages around the world, in plays such as Shakespeare’s Othello and the Gershwin brothers’ Porgy and Bess. His resonant bass-baritone voice made him a recording star as well, and by the 1930s, he became a box office sensation in the film Show Boat with his stirring rendition of “Ol Man River.”

Yet Robeson, who traveled the world and was purported to speak more than a dozen languages, became increasingly active in the rights of exploited workers, particularly blacks in the South, and he associated himself with communist causes from Africa to the Soviet Union. After a visit to Eastern Europe in 1934, where he was nearly attacked by Nazis in Germany, Robeson experienced nothing but adulation and respect in the USSR—a nation he believed did not harbor any resentment or racial animosity toward blacks. “Here, I am not a Negro but a human being for the first time in my life,” he said. “I walk in full human dignity.”

When communists invited him to the stage at the Paris Peace Congress, Robeson was urged to say a few words after an enthusiastic crowd heard him sing. French transcripts of the speech obtained by Robeson’s biographer Martin Duberman indicate that Robeson said, ”We in America do not forget that it is on the backs of the poor whites of Europe…and on the backs of millions of black people the wealth of America has been acquired. And we are resolved that it shall be distributed in an equitable manner among all of our children and we don’t want any hysterical stupidity about our participating in a war against anybody no matter whom. We are determined to fight for peace. We do not wish to fight the Soviet Union. ”

Lansing Warren, a correspondent covering the conference for the New York Times, reported a similar promise for peace in his dispatch for the newspaper, relegating Robeson’s comments toward the end of his story. But the Associated Press’s version of Robeson’s remarks read: “It is unthinkable that American Negros would go to war on behalf of those who have oppressed us for generations against the Soviet Union which in one generation has lifted our people to full human dignity.” (The source of that transcript remains unknown; the singer’s son Paul Robeson Jr. has said that because it was filed before his father actually spoke, the anonymous AP correspondent might have cobbled it together from remarks his father had previously made in Europe.)

By the next day, the press was reporting that Robeson was a traitor. According to Robeson Jr., his father had “no idea really that this was going on till they called him from New York and said, hey, you’d better say something, that you’re in immense trouble here in the United States.” Instead, Robeson continued his tour, deciding to address the “out of context” quotes when he returned, unaware of how much damage the AP account was doing to his reputation.

Unbeknownst to Robeson, Roy Wilkins and Walter White of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) were pressured by the U.S. State Department to issue a formal response to the singer’s purported comments. The NAACP, always wary of being linked in any way to communists, dissociated itself from Robeson. Channing Tobias, a member of the NAACP board of directors, called him “an ingrate.” Three months later, on July 18, 1949, Jackie Robinson was brought to Washington, D.C., to testify before HUAC for the purpose of obliterating Robeson’s leadership role in the American black community. The Brooklyn Dodgers’ second baseman assured Americans that Robeson did not speak for all blacks with his “silly” personal views. Everyone from conservatives to Eleanor Roosevelt criticized the singer. The former first lady and civil rights activist noted, “Mr. Robeson does his people great harm in trying to line them up on the Communist side of political picture. Jackie Robinson helps them greatly by his forthright statements.”

Uta Hagen as Desdemona and Paul Robeson as Othello on Broadway. Photo: United States Office of War Information

For Robeson, the criticism was piercing, especially coming from the baseball star. It was, after all, Robeson who was one of Jackie Robinson’s strongest advocates, and the singer once urged a boycott of Yankee Stadium because baseball was not integrated. Newspapers across the country praised Robinson’s testimony; one called it “four hits and no errors” for America. But lost in the reporting was the fact that Robinson did not pass up the chance to land a subtle dig at the communist hysteria that underlay the HUAC hearings. The committee chairs—including known Klan sympathizers Martin Dies Jr. of Texas and John Rankin of Mississippi—could not have been all smiles as Robinson finished speaking.

In a carefully worded statement, prepared with the help of Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey, Robinson said, “The fact that because it is a communist who denounces injustice in the courts, police brutality and lynching, when it happens, doesn’t change the truth of his charges.” Racial discrimination, Robinson said, is not “a creation of communist imagination.”

For his part, Robeson refused to be drawn into a personal feud with Robinson because “to do that, would be exactly what the other group wants us to do.” But the backlash against Robeson was immediate. His blacklisting and the revocation of his passport rendered him unable to work or travel, and he saw his yearly income drop from more than $150,000 to less than $3,000. In August 1949, he managed to book a concert in Peekskill, New York, but anti-civil rights factions within the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars caused a riot, injuring hundreds, thirteen of them seriously. One famous photograph from the riot pictured a highly decorated black World War I aviator being beaten by police and a state trooper. The press largely blamed communist agitators for provoking anti-American fervor.

Robeson’s name was stricken from the college All-America football teams. Newsreel footage of him was destroyed, recordings were erased and there was a clear effort in the media to avoid any mention of his name. Years later, he was brought before HUAC and asked to identify members of the Communist Party and to admit to his own membership. Robeson reminded the committee that he was a lawyer and that the Communist Party was a legal party in the United States; then he invoked his Fifth Amendment rights. He closed his testimony by saying, “You gentlemen belong with the Alien and Sedition Acts, and you are the nonpatriots, and you are the un-Americans, and you ought to be ashamed of yourselves.”

Toward the end of his life, Jackie Robinson had a chance to reflect on the incident and his invitation to testify before HUAC. He wrote in his autobiography, “I would reject such an invitation if offered now…. I have grown wiser and closer to the painful truths about America’s destructiveness. And I do have increased respect for Paul Robeson who, over the span of twenty years, sacrificed himself, his career and the wealth and comfort he once enjoyed because, I believe, he was sincerely trying to help his people.”

Sources

Books: Paul Robeson Jr. The Undiscovered Paul Robeson: Quest for Freedom, 1939-1976, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2010. Martin B. Duberman. Paul Robeson, Knopf, 1988. Paul Robeson, Edited with an Introduction by Philip S. Foner. Paul Robeson Speaks, Kensington Publishing Corp. 1978. Jackie Robinson. I Never Had it Made: An Autobiography, Putnam, 1972. Penny M. Von Eschen. Race Against Empire: Black Americans and Anticolonialism, 1937-1957, Cornell University, 1997. Joseph Dorinson, Henry Foner, William Pencak. Paul Robeson: Essays on His Life and Legacy, McFarland & Company, Inc., 2002. Lindsey R. Swindall. Intersections in Theatrics and Politics: The Case of Paul Robeson and Othello, Dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, 2007.

Articles: “Text of Jackie Robinson’s Testimony in DC: Famed Ballplayer Hits Discrimination In US.” The New Amsterdam News, July 23, 1949. “‘Not Mad At Jackie’—Robeson Tells Press,” Chicago Defender, July 30, 1949. “Truman, Mrs. FDR Hit Robeson Riot” Chicago Defender, September 17, 1949. “Paul Robeson and Jackie Robinson: Athletes and Activists at Armageddon,” Joseph Dorinson, Pennsylvania History, Vol. 66, No. 1, Paul Robeson (1898-1976) –A Centennial Symposium (Winter 1999). “Testimony of Paul Robeson before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, June 12, 1956.” http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/6440

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)