Sophie Blanchard – The High Flying Frenchwoman Who Revealed the Thrill and Danger of Ballooning

Blanchard was said to be afraid of riding in a carriage, but she became one of the great promoters of human flight

![]()

When Austrian skydiver Felix Baumgartner leaped from a capsule some 24 miles above earth on October 14, 2012, millions watched on television and the internet as he broke the sound barrier in a free fall that lasted ten minutes. But in the anticipation of Baumgartner’s jump (and his safe parachute landing), there was little room to marvel at the massive balloon that took him to the stratosphere.

More than 200 years ago in France, the vision of a human ascending the sky beneath a giant balloon produced what one magazine at the time described as “a spectacle the like of which was never shewn since the world began.” Early manned flights in the late 18th century led to “balloonomania” throughout Europe, as more than 100,000 spectators would gather in fields and city rooftops to witness the pioneers of human flight. And much of the talk turned to the French aeronaut Sophie Blanchard.

Known for being nervous on the ground but fearless in the air, Blanchard is believed to be the first female professional balloonist. She became a favorite of both Napoleon Bonaparte and Louis XVIII, who bestowed upon her official aeronaut appointments. Her solo flights at festivals and celebrations were spectacular but also perilous, and in the summer of 1819, she become the first woman to be killed in an aviation accident.

She was born Marie Madeleine-Sophie Armant in Trois-Canons in 1778, not long before the Montgolfier brothers, Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Etienne began experimenting with balloons made from sackcloth and taffeta and lifted by heated air from fires in a box below. As the Montgolfiers’ balloons became larger and larger, the brothers began to consider manned flight. Louis XVI took an interest and proposed sending two criminals into the sky to test the contraption, but the brothers chose instead to place a sheep, a duck and a rooster on board for the first balloon flight to hold living creatures. In a 1783 demonstration before the King and Marie Antoinette and a crowd at the royal palace in Versailles, the Montgolfier brothers saw their craft ascend 1,500 into the air. Less than ten minutes later, the three animals landed safely.

Just months later, when Etienne Montgolfier became the first human rise into the skies, on a tethered balloon, and not long after, Pilatre de Rozier and French marquis Francois Laurent le Vieux d’Arlandes made the first human free flight before Louis XVI, U.S. envoy Benjamin Franklin and more than 100,000 other spectators.

Balloonomania had begun, and the development of gas balloons, made possible by the discovery of hydrogen by British scientist Henry Cavendish in 1766, quickly supplanted hot-air balloons, since they could fly higher and further. More and more pioneers were drawn to new feats in ballooning, but not everyone was thrilled: Terrified peasants in the English countryside tore a descending balloon to pieces.

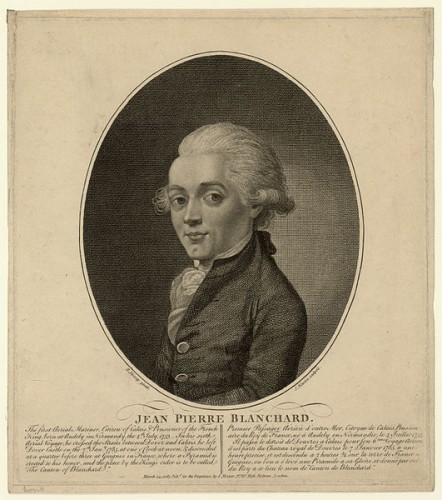

A child of this pioneering era, Sophie Armant married Jean-Pierre Blanchard, a middle-aged inventor who had made his first balloon flight in Paris when she was just five years old. (The date of their marriage is unclear.) In January 1785, Blanchard and John Jeffries, an American doctor, became the first men to fly over the English Channel in a hydrogen balloon, flying from England to France. (Pilatre de Rozier, trying to cross the channel from France to England later that year, became the first known aviation fatality after his balloon deflated at 1,500 feet.)

Jean-Pierre Blanchard began to tour Europe. At demonstrations where he charged for admission, he showed off his silk balloons, dropped parachute-equipped dogs and launched fireworks from above. “All the World gives their shilling to see it,” one newspaper reported, citing crowds affected with “balloon madness” and “aeriel phrenzy.” Spectators were drawn to launches with unique balloons shaped like Pegasus and Nymp, and they thrilled to see men risk their lives in flights where fires often sent balloons plummeting back to earth.

“It may have been precisely lack of efficiency that made the balloon such an appropriate symbol of human longings and hopes,” historian Stephan Oettermann noted. “Hot-air balloons and the gas balloons that succeeded them soon after belong not so much to the history of aviation as to the still-to-be-written account of middle class dreams.”

Furniture and ceramics at the time were decorated with images of balloons. European women’s clothing featured puffy sleeves and rounded skirts. Jean-Pierre Blanchard’s coiffed hair became all the rage among the fashionable. On a trip to the United States in 1793 he conducted the first balloon flight in North America, ascending over Philadelphia before the likes of George Washington, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson.

But not everything Blanchard did succeeded. He escaped a mid-air malfunction by cutting his car from his balloon and using the latter as a parachute. He falsely marketed himself as the inventor of the balloon and the parachute. He established the “Balloon and Parachute Aerostatic Academy” in 1785, but it quickly failed. John Jeffries, Blanchard’s English Channel crossing partner and chief financier, later claimed that Blanchard tried to keep him from boarding the balloon by wearing weighted girdles and claiming the balloon could carry only him.

Facing ruin, Blanchard (who had abandoned his first wife and their four children to pursue his ballooning dreams) persuaded his new wife to ride with him, believing that a flying female might be a novel enough idea to bring back the paying crowds.

Tiny, nervous, and described by one writer as having “sharp bird-like features,” Sophie Blanchard was believed to be terrified of riding in horse-drawn carriages. Yet once in a balloon, she found flight to be a “sensation incomparable,” and not long after she and her husband began ascents together, she made her first solo ascent in 1805, becoming the first woman to pilot her own balloon.

The Blanchards made a go of it until 1809—when Jean-Pierre, standing beside Sophie in a basket tethered to a balloon flying over the Hague, had a heart attack and fell to his death. Crippled by her husband’s debts, she continued to fly, slowly paying off creditors and accentuating her shows with fireworks that she launched from the sky. She became a favorite of Napoleon’s, who chose her the “aeronaut of the official festivals.” She made an ascent to celebrate his 1810 wedding to Marie Louise.

Napoleon also appointed her chief air minster of ballooning, and she worked on plans for an aerial invasion of England by French troops in balloons—something she later deemed impossible. When the French monarchy was restored four years later, King Louis XVIII named her “official aeronaut of the restoration.”

She had made long-distance trips in Italy, crossed the Alps and generally did everything her husband had hoped to do himself. She paid off his debts and made a reputation for herself. She seemed to accept, even amplify, the risks of her career. She preferred to fly at night and stay out until dawn, sometimes sleeping in her balloon. She once passed out and nearly froze at altitude above Turin after ascending to avoid a hailstorm. She nearly drowned after dropping into a swamp in Naples. Despite warnings of extreme danger, she set off pyrotechnics beneath her hydrogen balloon.

Finally, at the age of 41, Sophie Blanchard made her last flight.

On the evening of July 6, 1819, a crowd gathered for a fete at the Tivoli Gardens in Paris. Sophie Blanchard, now 41 but described as the “still young, sprightly, and amiable” aeronaut, rose from the lawn to a flourish of music and flare of fireworks. Despite the misgivings of others, she had planned to do her “Bengal Fire” demonstration, a slow-burning pyrotechnics display. As she mounted her balloon she said, “Allons, ce sera pour la derniere fois” (“Let’s go, this will be for the last time”).

In an elaborate white dress and matching hat accessorized with an ostrich plume, Blanchard, carrying a torch, began her ascent. Winds immediately carried her away from the gardens. From above, she lit fireworks and dropped them by parachute; Bengal lights hung from beneath her balloon. Suddenly there was a flash and popping from the skies; flames shot up from the top of the balloon.

“Beautiful! Beautiful! Vive Madame Blanchard,” shouted someone in the crowd. The balloon began to descend; it was on fire. “It lighted up Paris like some immense moving beacon,” read one account.

Blanchard prepared for landing as the balloon made a slow descent, back over the gardens along the Rue de Provence. She cut loose ballast to further slow the fall, and it looked as though she might make it safely to the ground. Then the basket hit the roof of a house and Blanchard tipped out, tumbling along the roof and onto the street, where, according to a newspaper account, “she was picked up dead.”

While all Europe mourned the death of Sophie Blanchard, some cautioned, predictably, that a balloon was no place for a woman. She was buried in Pere Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, beneath a tombstone representing her balloon in flames, with the epitaph Victime de son Art et de son Intrepidite (Victim of her art and intrepidity).

Sources

Articles: “The ‘Balloonomania’: Science and Spectacle in 1780s England,” by Paul Keen, Eighteenth Century Studies, Summer 2006, 39, 4. “Consumerism and the Rise of Balloons in Europe at the End of the Eighteenth Century,” by Michael R. Lynn, Science in Context, Cambridge University Press, 2008. “Madame Blanchard, the Aeronaut,” Scientific American Supplement #195, September 27, 1879. “Sophie Blanchard—First Woman Balloon Pilot,” Historic Wings, July 6, 2012, http://fly.historicwings.com/2012/07/sophie-blanchard-first-woman-balloon-pilot/ “How Man Has Learned to Fly,” The Washington Post, October 10, 1909.

Books: Paul Keen, Literature, Commerce, and the Spectacle of Modernity, 1750-1800, Cambridge University Press, 2012.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)