The Day Henry Clay Refused to Compromise

The Great Pacificator was adept at getting congressmen to reach agreements over slavery. But he was less accommodating when one of his own slaves sued him

![]()

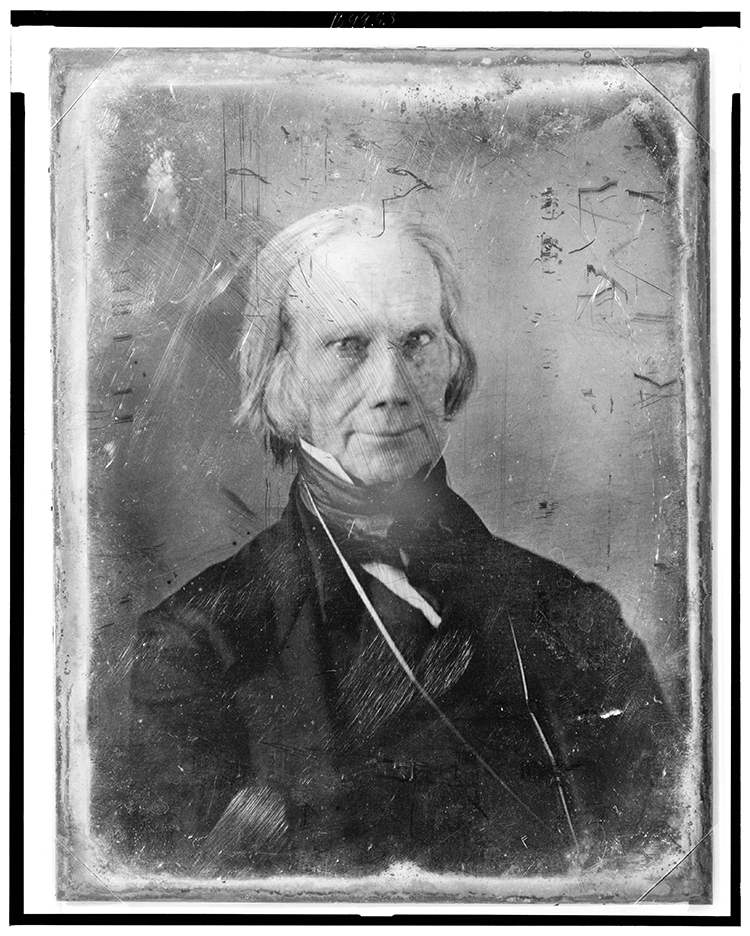

To this day, he is considered one of the most influential politicians in U.S. history. His role in putting together the Compromise of 1850, a series of resolutions limiting the expansion of slavery, delayed secession for a decade and earned him the nickname “the Great Pacificator.” Indeed, Mississippi Senator Henry S. Foote later said, “Had there been one such man in the Congress of the United States as Henry Clay in 1860-’61 there would, I feel sure, have been no civil war.”

Clay owned 60 slaves. Yet he called slavery “this great evil…the darkest spot in the map of our country” and did not modify his stance through five campaigns for the presidency, all of which failed. “I’d rather be right than be president,” he said, famously, during an 1838 Senate debate, which his critics (he had many) attributed to sour grapes, a sentiment spoken only after he’d been defeated. Throughout his life, Clay maintained a “moderate” stance on slavery: He saw the institution as immoral, a bane on American society, but insisted that it was so entrenched in Southern culture that calls for abolition were extreme, impractical and a threat to the integrity of the Union. He supported gradual emancipation and helped found the American Colonization Society, made up of mostly Quakers and abolitionists, to promote the return of free black people to Africa, where, it was believed, they would have better lives. The organization was supported by many slaveowners, who believed that free blacks in America could only lead to slave rebellion.

Clay’s ability to promote compromise in the most complex issues of the day made him a highly effective politician. Abraham Lincoln said Clay was “the man for a crisis,” adding later that he was “my beau ideal of a statesman, the man for whom I fought all my humble life.”

Yet there was one crisis in Henry Clay’s life in which the Great Pacificator showed no desire to compromise. The incident occurred in Washington, D.C., when he was serving as secretary of state to President John Quincy Adams. In 1829, Charlotte Dupuy, Clay’s longtime slave, filed a petition with the U.S. Circuit Court against him, claiming she was free. The suit “shocked and angered” Clay, and whatever sympathies he held with regard to human rights did not extinguish his passion for the rule of law. When confronted with what he considered a “groundless writ” that might result in the loss of his rightful property, Henry Clay showed little mercy in fighting the suit.

The Decatur House, on Lafayette Square in Washington, D.C., where Henry Clay’s slave Charlotte Dupuy lived and worked. Photo: Wikipedia

Born into slavery around 1787 in Cambridge, Maryland, Charlotte Stanley was purchased in 1805 by a tailor named James Condon, who took the 18 year-old girl back to his home in Kentucky. The following year, she met and married Aaron Dupuy, a young slave on the 600-acre Ashland plantation in Lexington, owned by Henry Clay—who then purchased her for $450. The young couple would have two children, Charles and Mary Ann Dupuy.

In 1809, Clay was to elected to fill retiring Senator John Adair’s unexpired term at the age of 29—below the constitutionally required age of 30, but no one seemed to notice or care. The Dupuys accompanied him to Washington, where they lived and worked as house slaves for the congressman at the Decatur House, a mansion on Lafayette Square, near the White House. In 1810, Clay was elected to the House of Representatives, where he spent most of the next 20 years, serving several terms as speaker.

For those two decades the Dupuys, though legally enslaved, lived in relative freedom in Washington. Clay even allowed Charlotte to visit her family on Maryland’s Eastern Shore on several occasions—visits Clay later surmised were “the root of all the subsequent trouble.”

But in 1828 Adams lost in his re-election campaign to another of Clay’s rivals, Andrew Jackson, and Clay’s term as secretary of state came to an end. It was as he was preparing to return to Kentucky that Charlotte Dupuy filed her suit, based on a promise, she claimed, made by her former owner, James Condon, to free her after her years of service to him. Her case long predated the Dred Scott suit, which would result in the Supreme Court’s 1857 ruling that the federal government had no power to regulate slavery in the territories, that the Constitution did not apply to people of African descent and that they were not U.S. citizens.

Dupuy’s attorney, Robert Beale, argued that the Dupuys should not have to return to Kentucky, where they would “be held as slaves for life.” The court agreed to hear the case. For 18 months, she stayed in Washington, working for wages at the Decatur House for Clay’s successor as secretary of state, Martin Van Buren. Meanwhile, Clay stewed in Kentucky. The court ultimately rejected Dupuy’s claim to freedom, ruling that Condon sold her to Clay “without any conditions,” and that enslaved persons had no legal rights under the constitution. Clay then wrote to his agent in Washington, Philip Fendall, encouraging him to order the marshal to “imprison Lotty.” He added that her husband and children had returned with him to Kentucky, and that Charlotte’s conduct had created “insubordination among her relatives here.” He added, “Her refusal therefore to return home, when requested by me to do so through you, was unnatural towards them as it was disobedient to me…. I think it high time to put a stop to it…How shall I now get her, is the question?”

Clay arranged for Charlotte to be put in prison in Alexandria, Virginia. “In the mean time,” he wrote Fendall, “be pleased to let her remain in jail and inform me what is necessary for me to do to meet the charges.” She was eventually sent to New Orleans, where she was enslaved at the home of Clay’s daughter and son-in-law for another decade. Aaron Dupuy continued to work at the Ashland plantation, and it was believed that neither Clay nor the Dupuys harbored any ill will after the freedom suit was resolved—an indication, some historians have suggested, that Clay’s belief that his political adversaries were behind Charlotte Dupuy’s lawsuit was well-founded.

In 1840, Henry Clay freed Charlotte and her daughter, Mary Ann. Clay continued to travel the country with her son, Charles, as his manservant. It was said that Clay used Charles as an example of his kindness toward slaves, and he eventually freed Charles in 1844. Aaron Dupuy remained enslaved to Clay until 1852, when he was freed either before Clay’s death that year, or by his will.

Lincoln eulogized Henry Clay with the following words:

He loved his country partly because it was his own country, but mostly because it was a free country; and he burned with a zeal for its advancement, prosperity and glory, because he saw in such, the advancement, prosperity and glory, of human liberty, human right and human nature. He desired the prosperity of his countrymen partly because they were his countrymen, but chiefly to show to the world that freemen could be prosperous.

Sources

Books: David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler, Henry Clay: The Essential American, Random House, 2010. Jesse J. Holland, Black Men Built the Capital: Discovering African American History in and Around Washington, D.C., Globe Pequot, 2007.

Articles: “The Half Had Not Been Told Me: African Americans on Lafayette Square, 1795-1965, Presented by the White House Historical Association and the National Trust for Historic Preservation,” http://www.whitehousehistory.org/decatur-house/african-american-tour/content/Decatur-House ”Henry Clay and Ashland,” by Peter W. Schramm, The Ashbrook Center at Ashland University, http://ashbrook.org/publications/onprin-v7n3-schramm/ ”Henry Clay: Young and in Charge,” by Claire McCormack, Time, October 14, 2010. “Henry Clay: (1777-1852),” by Thomas Rush, American History From Revolution to Reconstruction and Beyond, http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/biographies/henry-clay/ “American History: The Rise of the Movement Against Slavery,” The Making of a Nation, http://www.manythings.org/voa/history/67.html “Eulogy on Henry Clay, July 6, 1952, Springfield, Illinois, Abraham Lincoln Online, Speeches and Writing, http://showcase.netins.net/web/creative/lincoln/speeches/clay.htm

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)