How American Rich Kids Bought Their Way Into the British Elite

The nouveau riche of the Gilded Age had buckets of money but little social standing—until they started marrying their daughters to British nobles

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130813115130marlborough-vanderbilt-wedding-history-small.jpg)

Consuelo Vanderbilt’s wedding day had finally arrived, and all of New York (and then some) was aflutter. Crowds lined Fifth Avenue, hoping to catch a glimpse of the bride on her way to St. Thomas Episcopal Church. She was quite possibly the most celebrated of all the young heiresses who captured the attention of Gilded Age Americans, and her wedding was the peak of a trend that had, in recent decades, taken the world by storm: American girls, born to the richest men in the country, marrying British gentlemen with titles and centuries of noble lineage behind them.

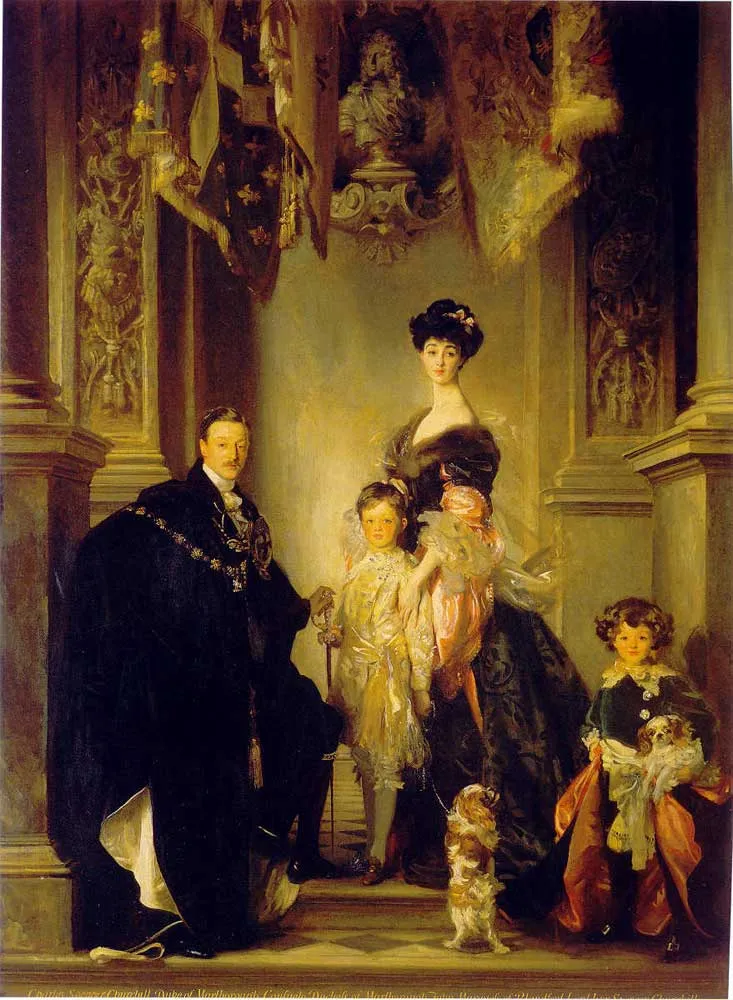

Consuelo’s catch was considered one of the finest—Charles Spencer-Churchill, the future Ninth Duke of Marlborough, who stood to become lord of Blenheim, an estate second only to Buckingham Palace. The bride, already considered American royalty, would become a duchess, bestowing upon her family the highest social standing (for which her mother, Alva, who was often snubbed by “old New York”, and who viewed her husband’s money as gauche, was desperate).

And yet on November 6, 1895, the bride was less than thrilled:

I spent the morning of my wedding day in tears and alone; no one came near me. A footman had been posted at the door of my apartment and not even my governess was admitted. Like an automaton I donned the lovely lingerie with its real lace and the white silk stockings and shoes…. I felt cold and numb as I went down to meet my father and the bridesmaids who were waiting for me.

Conseulo Vanderbilt loved another—a rich other, but an American without a title or an English country estate. But her marriage to Marlborough was non-negotiable.

Beginning in the 1870s, American girls with money had been flocking to Britain in droves, ready to exchange railroad cash and mining stocks for the right to call themselves “Lady.” (“Downton Abbey” fans will surely recognize Cora Crawley as one of their ilk.) The appeal was clear. The heiresses, unlikely to be admitted to the highest ranks of New York society, would gain entry to an elite social world, and who needed Mrs. Astor’s drawing room when she could keep company with HRH the Prince of Wales?

And Britain’s upper crust would get a much-needed infusion of cash. For a British gentleman to work for money was unthinkable. But by the end of the 19th century it cost more to run a country estate than the estate could make for itself, and the great houses slid dangerously close to disrepair. By marrying a Vanderbilt or a Whitney, a future duke could ensure not just the survival of his family’s land and name, but also a life enhanced by easy access to money, something he certainly wouldn’t get if he married a peer.

By 1895 (a year in which America sent nine daughters to the peerage), the formula had coalesced into a relatively simple process. Mothers and their daughters would visit London for the social season, relying upon friends and relatives who had already made British matches to make introductions to eligible young men. Depending on the fortunes of the girl in question, several offers would be fielded, and her parents, weighing social and financial investments and returns, would make a selection. So such marriages were basically transactional alliances. Even in 1874, the union of Jennie Jerome and Lord Randolph Churchill—which would give the Western world both Winston Churchill and a great deal to talk about—would reflect the beginnings of the trend.

Born in Brooklyn in 1854, dark-haired Jennie captivated Lord Randolph, son of the seventh Duke of Marlborough, with startling suddenness. Within three days of their initial meeting, Jennie and Randolph announced their plans to marry.

Neither the Jeromes nor the Randolphs were thrilled. Jennie’s parents thought Lord Randolph, in proposing to their daughter before consulting with them, was in serious breach of etiquette. Not to mention that, as a second son, he wouldn’t inherit his father’s title.

The Randolphs were aghast at their son’s choice of an American bride from a family no one knew anything about, and the more they learned about the Jeromes, the more they disliked the match. Leonard Jerome, Jennie’s father, was a flamboyant speculator in stocks and a noted chaser of comely opera singers; her mother, Clara, was occasionally accused of having Iroquois ancestry. Despite owning property in the right part of town (the Jerome Mansion stood at the corner of 26th Street and Madison Avenue), the Jeromes were not considered worthy of the upper echelons of New York society.

Jerome, the duke wrote to his lovestruck son, “drives about six and eight horses in New York (one may take this as an indication of what the man is).” Despite his daughter’s charms, he was a person “no man in his sense could think respectable.”

The Jeromes, though, had two advantages that could not be overlooked. The first was a personal endorsement of the match by Edward, Prince of Wales, who had met Jennie in social settings and liked her. The second was pecuniary.

Randolph had no money of his own, and the measly allowance his father provided would not have been enough for the couple to live on. The Jeromes would be aligning themselves with one of Britain’s most noble families, and for that they were expected to pay handsomely. Leonard Jerome came up with 50,000 pounds plus a 1,000-pound yearly allowance for Jennie (something unheard-of in British families), and the deal was done. In April 1874, Jennie and Randolph were married.

Seven months after the wedding, Lady Randolph gave birth to Winston. (She claimed a fall had induced premature labor, but the baby appeared full-term.) A second followed in 1880, though motherhood did not seem to have slowed Jennie’s quest for excitement. She and Randolph both had extramarital affairs (she, it was rumored, with the Prince of Wales, even as she remained close with Princess Alexandra, his wife), though they remained married until his death, in 1895. (The jury is still out on whether he died of syphilis contracted during extracurricular activities.)

Jennie came to have great influence over the political careers of her husband and son, and remained a force on the London social scene into the 20th century. She also came to represent what the British saw as the most vital kind of American girl—bright, intelligent and a bit headstrong. When Jennie’s essay “American Women in Europe” was published in the Pall Mall Magazine in 1903, she asserted, “the old prejudices against them, which mostly arose out of ignorance, have been removed, and American women are now appreciated as they deserve.” They were beautiful (Jennie Chamberlain, an heiress from Cleveland, so charmed the Prince of Wales he followed her from house party to house party during one mid-1880s social season), well-dressed (they could afford it) and worldly in a way their English counterparts were not. As Jennie Churchill wrote:

They are better read, and have generally traveled before they make their appearance in the world. Whereas a whole family of English girls are educated by a more or less incompetent governess, the American girl in the same condition of life will begin from her earliest age with the best professors…by the time she is eighteen she is able to assert her views on most things and her independence in all.

Despite their joie de vivre, not all American brides were as adaptable as Lady Randolph, and their marriages not as successful. The Marlborough-Vanderbilt match, for one, was significantly less harmonious.

Alva Vanderbilt determined early on that only a noble husband would be worthy of her daughter. She and a team of governesses managed Consuelo’s upbringing in New York and Newport, Rhode Island, where the heiress studied French, music and other disciplines a lady might need as a European hostess. Consuelo was meek, deferring to her mother on most matters. Before the wedding she was described by the Chicago Tribune as having “ all the naive frankness of a child,” an affectation that may have endeared her to the American public, but would be no match for the heir to Blenheim. After they met at the home of Minnie Paget (nee Stevens), a minor American heiress who acted as a sort of matchmaker, Alva went to work ensuring the union would take place. It was settled that the groom would receive $2.5 million in shares of stock owned by Consuelo’s father, who would also agree to guarantee the yearly sum of $100,000 to each half of the couple.

“Sunny,” as the future duke was known, made little effort to hide his reasons for favoring an American bride; Blenheim Palace needed repairs his family couldn’t afford. After the wedding (it is rumored that in the carriage ride after the ceremony, Sunny coldly informed Consuelo of the lover waiting for him in England) he went about spending her dowry restoring the family seat to glory.

Consuelo, for her part, was less than pleased with her new home:

Our own rooms, which faced east, were being redecorated, so we spent the first three months in a cold and cheerless apartment looking north. They were ugly, depressing rooms, devoid of the beauty and comforts my own home had provided.

Unlike her previous American residences, Blenheim lacked indoor plumbing, and many of the rooms were drafty. Once installed there, some 65 miles from London, Consuelo would travel little until the next social season (she was lucky, though; some American brides wound up on estates in the North of England, where getting to the capital more than once a year was unthinkable), and in the drawing room she was forced to answer questions nightly about whether she was yet in the family way. If Consuelo failed to produce an heir, the dukedom would pass to Winston Churchill (Lady Randolph’s son), something the current duchess of Marlborough was loath to see happen.

Consuelo and Sunny’s relationship deteriorated. He returned to the womanizing he’d done before their marriage, and she looked elsewhere for comfort, engaging for a time in a relationship with her husband’s cousin, the Hon. Reginald Fellowes. These dalliances were not enough to keep the Marlboroughs happy, and in 1906, barely ten years after their wedding, they separated, divorcing in 1921.

If the Vanderbilt-Marlborough marriage was the high point of the American ascent to the noble realm, it was also the beginning of a backlash. Sunny’s courtship of Consuelo was seen as almost mercenary, and the men who followed him in the hunt for an heiress looked even worse. When Alice Thaw, daughter of a Pittsburgh railroad magnate, agreed to marry the earl of Yarmouth in 1903, she hardly could have guessed that on the morning of her wedding the groom would be arrested for failure to pay outstanding debts and that she would have to wait at the church while her intended and her father renegotiated her dowry.

American fathers, too, began to doubt the necessity of having a duchess in the family. Frank Work, whose daughter Frances’ marriage to James Burke Roche, Baron Fermoy, would end with Frances accusing her husband of desertion, went on record as strongly opposing the practice of trading hard-earned money for louche husbands with impressive names. His 1911 obituary, printed in the New-York Tribune, quoted from an earlier interview:

It’s time this international marrying came to a stop for our American girls are ruining our own country by it. As fast as our honorable, hard working men can earn this money their daughters take it and toss it across the ocean. And for what? For the the purpose of a title and the privilege of paying the debts of so-called noblemen! If I had anything to say about it, I’d make an international marriage a hanging offense.

Ideal marriages, wealthy fathers thought, were like the 1896 match between Gertrude Vanderbilt and Henry Payne Whitney, wherein American money stayed put and even had the chance to multiply.

Much of the Gilded Age matchmaking that united the two nations occurred under the reign of Edward VII, who as Prince of Wales encouraged social merriment equal to that of his mother Queen Victoria’s sobriety. When Edward died, in 1910, the throne passed to his son George V, who, along with his British-bred wife, Mary, curtailed the excess that had characterized his father’s leadership of Britain’s leisure class. Nightly private parties throughout a social season began to seem vulgar as Europe moved closer to war. In New York, Newport and Chicago, the likes of Caroline Astor began to cede social power to the nouveaux riche they had once snubbed, and as the American economy became the domain of men like J.P. Morgan and Andrew Carnegie, their daughters had little reason to spend their inheritances restoring 17th-century castles when they could stay home and be treated as royalty by the press and the public.

Though American girls quit looking for husbands across the pond, the influence of the ones who did become duchesses and baronesses left an indelible mark on the British landscape. American women financed the repair and restoration of once-shabby estates like Blenheim and Wrotham Park, backed political ambitions (Mary Leiter, a department-store heiress from Chicago, used her father’s money to help her husband, George Curzon, become the viceroy of India), and, in the case of Jennie Jerome, gave birth to children who would lead Britain squarely into the 20th century.

The women, too, were changed. Jennie Jerome, after her husband’s death, married two more Englishmen (one of them younger than her son Winston), and other American girls who divorced or outlived their first husbands stayed on in their adoptive country, occasionally marrying other peers and tending to the political and marital careers of their children.

After she divorced Sunny, Consuelo Vanderbilt married Lt. Jacques Balsan, a French balloonist and airplane pilot, and the two would remain together until his death in 1956, living primarily in a château 50 miles from Paris and, later, a massive Palm Beach estate Consuelo called Casa Alva, in honor of her mother.

Consuelo’s autobiography, The Glitter and the Gold, appeared in 1953 and detailed just how miserable she’d been as the Duchess of Marlborough. But perhaps, during her time as a peer of the realm, something about that life took hold of Consuelo and never quite let go. She died on Long Island in 1964, having asked her family to secure her a final resting place at Blenheim.

Sources:

Balsan, Consuelo, The Glitter and the Gold, 1953; Lady Randolph Churchill, “American Women in Europe,” Nash’s Pall Mall Magazine, 1903; DePew, Chauncey, Titled Americans 1890: A List of American Ladies Who Have Married Foreigners of Rank; MacColl, Gail, and Wallace, Carol McD., To Marry an English Lord, Workman Publishing, 1989; Sebba, Anne, American Jennie: The Remarkable Life of Lady Randolph Churchill, W.W. Norton & Company, 2007; Cannadine, David, The Rise and Fall of the British Aristocracy, Vintage, 1999; Lovell, Mary S., The Churchills, Little Brown, 2011; Stuart, Amanda Mackenzie, Consuelo and Alva Vanderbilt: The Story of a Daughter and Mother in the Gilded Age, Harper Perennial, 2005; “Frank Work Dead at 92”, New-York Tribune, 17 March 1911; “The Marriage of Marlborough and Vanderbilt,” Chicago Daily Tribune, 27 October 1895; “She is Now a Duchess,” New York Times, 7 November 1895.