Patient, Heal Thyself

Cutting-edge research in regenerative medicine suggests that the future of health care may lie in getting the body to grow new parts and heal itself.

![]()

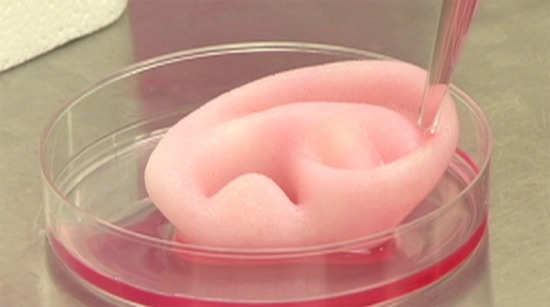

An ear grown from human cells. Photo courtesy of Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center.

Until last week, I don’t think I’d ever heard of the African spiny mouse. I’m guessing I’m probably not alone.

Apparently, they’re nice pets if you prefer an other-side-of-the-glass relationship. No question they’re cute things, only six inches or so long if you count their tails, and they have a rep for sucking down a lot of water. Oh, and you’re not supposed to pick them up by their tails.

Turns out the tail thing–namely that it can come off with great ease–is why this little furball was in the news. It’s also the reason the African spiny mouse could end up playing a big role in the future of medicine.

A study published in the journal Nature reported that not only can the mouse effortlessly lose its tail to escape predators, but it also can have its skin tear off and then grow back. This, however, is more than just some bizarre animal stunt like the lizards that shoot blood from their eyes. Salamanders can replace lost legs, fish can grow new fins, but mammals aren’t supposed to be able to regrow body parts.

Skin off my back

Mammals scar after they tear their skin. But not the spiny mouse. It can lose more than 50 percent of its skin and then grow a near perfect replacement, including new hair. Its ears are even more magical. When scientists drilled holes in them, the mice were able to not only grow more skin, but also new glands, hair follicles and cartilage.

And that’s what really excites researchers in human regenerative medicine, a fast-emerging field built around finding ways to boost the body’s ability to heal itself. As amazingly sophisticated as medicine has become, treatment of most diseases still focuses largely on managing symptoms–insulin shots to keep diabetes in check, medications to ease the strain on a damaged heart.

But regenerative medicine could dramatically change health care by shifting the emphasis to helping damaged tissue or organs repair themselves. Some already see it leading to a potential cure for Type 1 diabetes, as bone marrow stem cells have shown an ability to generate pancreas cells that produce insulin.

Another regenerative medicine procedure, in which a person’s own white blood cells and platelets are injected into an injured muscle or joint, is becoming popular, particularly among professional athletes, as a way of speeding up rehabilitation.

There’s also “spray-on skin,” created from neonatal stem cells. It’s proving to be a more effective and less painful way to treat burns and ulcers than skin grafts. And, at the Wake Forest Baptist Medical School, they’ve gone a step further, developing a process in which skin cells are essentially “printed” on burn wounds.

The wounds of war

That project at Wake Forest and, in fact, much of the cutting-edge research in regenerative medicine in the U.S., is funded through a Defense Department program called AFIRM, short for the Armed Forces Institute of Regenerative Medicine. It was launched in 2008, with the purpose of fast-tracking more innovative and less invasive ways to deal with the horrific burns, shattered limbs and other awful injuries suffered by soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan.

A case in point is Sgt. Ron Strang, a Marine whose thigh was ripped apart by a roadside bomb in Afghanistan. The gaping wound “healed,” but not really. Without much of a quadriceps muscle, Strang kept falling over.

So doctors at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center tried something new. They stitched a sheet made from a pig’s bladder into Strang’s leg. That’s known as scaffolding, cell material that scientists now know signals the body to start repairing tissue. Put simply, it tells stem cells to come to the site and develop into muscle cells.

And that’s what they did, so much so that Sgt. Strang can now run on a treadmill. As one of his doctors, Stephen Badylak, told the New York Times: “We’re trying to work with nature rather than fight nature.”

In another AFIRM project geared to help disfigured soldiers, researchers have been able to grow an almost perfectly-shaped human ear inside a lab dish–all from cartilage cells taken from inside the person’s nose. If the FDA approves the process, they hope to start attaching lab-grown ears to patients within a year.

Regrowth spurts

Here are other new developments in regenerative medicine:

- Grow your own: Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center found that liver cells, thymus tissue and pancreatic cells that produce insulin all can thrive within lymph nodes. And that provides a potential opportunity to grow organ cells in a body instead of needing to do full organ transplants.

- Gut check: A study at the University of Nevada discovered that a type of stem cell found in cord blood has the ability to migrate to the intestine and contribute to the cell population there. And that could lead to a new treatment for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

- This guy’s going to need a little more toner: Engineers at the University of California at San Diego have been able to fabricate 3D structures out of soft hydrogels, which makes it easier to imagine creating body parts from tissues produced on a printer.

- Blind luck: This summer, surgeons in California implanted embryonic stem cells, specially grown in a lab, into the eyes of two patients going blind. They were the first of 24 people who will be given the experimental treatment as part of a clinical trial approved by the FDA.

- In your face, Hair Club for Men Earlier this year a team at the Tokyo University of Science were able to develop fully functioning hair follicles by transplanting human adult stem cells into the skin of bald mice.

Video bonus: See for yourself black human hair growing out of the back of the neck of a bald mouse. Thank goodness it’s for science because it’s not a good look.

More from Smithsonian.com

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/randy-rieland-240.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/randy-rieland-240.png)