How a Documentary Gets Made

A primer on where the documentary got its start and how the film genre gets its funding

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120314031045Girl_Walk-thumb.jpg)

My post Watching Movies in the Cloud discussed the implications of streaming movies onto your computer. It focused on the end result: how watching movies on your computer compared with watching them in a theater. But commenter Paul Kakert raised a very good point. Where are new movies, in particular documentaries, coming from? Will streaming affect the subject matter of the movies themselves, and not just their sound and image? Can you find worthwhile titles in the cloud that haven’t played in theaters?

Kakert cited his nonprofit, the Iowa-based Storytellers International, which promotes and distributes its titles through DocumentaryTV.com. Documentaries are a chronically underfunded genre, and it’s almost as difficult to get them into theaters as it is to make them.

Several documentary distributors have established online sites, including Appalshop, where you can stream Mimi Pickering’s troubling Buffalo Creek Flood: an Act of Man; Documentary Educational Resources (DER), which offers the Alaskan films by Sarah Elder and Len Kamerling; Docurama Films, covering arts, social issues, and ethnic documentaries; Kartemquin Films, the organization behind Hoop Dreams; Frederick Wiseman’s Zipporah Films; and many others. Independent distributors like Milestone, Criterion, and Kino also offer documentary titles.

What sets something like Kartemquin Films apart from distributors is that Kartemquin also helps produce titles. Traditionally it’s been very difficult to get money to make documentaries. Robert Flaherty, about whose films the critic John Grierson coined the very word “documentary,” struggled throughout his career to finance his projects. Nanook of the North, one of the most famous titles in the genre, was paid for in part by the French furrier John Revillon. Once Nanook became a box-office hit, Flaherty signed with the Hollywood studio Paramount.

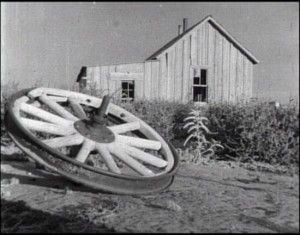

Paramount was remarkably adventurous in the 1920s, financing Flaherty and the filmmaking team of Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, at the time making documentaries like Grass and Chang, but soon to stun the world with King Kong. Most studios established footholds in the genre, usually through newsreels and short subjects. By far the biggest sponsor of documentaries was the government, both on local and federal levels. The state of Connecticut produced educational films on everything from hygiene to citizenship, while in the 1930s, Washington, DC, became a haven for artists like Flaherty, Pare Lorentz, and Virgil Thompson.

Government involvement in film production spiked during World War II, when the film industry’s top leaders either enlisted or cooperated with propaganda efforts. After the war, documentarians went back to scrounging for money. Flaherty’s Louisiana Story (1949) was financed by Standard Oil, while John Marshall’s The Hunters (1957) received funding from the Peabody Museum at Harvard and the Smithsonian. Many fledgling filmmakers turned to the United States Information Agency, or USIA, the government’s overseas propaganda arm.

Documentarians became adept at freelancing. David and Albert Maysles made television commercials for Citibank. D A Pennebaker worked on ABC’s Living Camera series. Wiseman signed a contract with WNET, the New York City public television outlet.

In fact, public television has become a prime outlet for documentaries. Adapted from the BBC series Horizon, NOVA has acquired or produced scores of documentaries since its inception in 1974. Created in 1984, American Masters offers biographies of artists like Margaret Mitchell and Merle Haggard. Since 1988, POV has screened some 300 independent documentaries, including works by Wiseman, the Maysles, and Errol Morris.

For the past decades, HBO Documentary Films has dominated the commercial front, due in large part to Sheila Nevins, who is responsible for developing, producing, and acquiring documentaries for HBO and Cinemax. (Full disclosure: I worked in HBO’s story department back in the 1990s.) Nevins exerts remarkable influence, as director Joe Berlinger told me last fall.

“Sheila Nevins was a big fan of Brother’s Keeper, our first film,” Berlinger said. “After it had a nice run, she sent us a little article, a clipping that had made it to like page B20 of the New York Times, an AP wire service story picked up from a local paper.” That was the basis for Purgatory Lost, a trilogy of documentaries Berlinger and co-director Bruce Sinofsky made about the West Memphis Three.

HBO and PBS operate like the major leagues for documentarians, suggesting topics, funding research, providing publicity and all-important exposure. But what if you haven’t made a documentary yet? How do you get funding?

In his blog The Front Row, New Yorker writer and editor Richard Brody linked to a fascinating Steven Spielberg interview in which the director claimed that right now is a great time to make movies. The director was quoted:

You shouldn’t dream your film, you should make it! If no one hires you, use the camera on your phone and post everything on YouTube. A young person has more opportunities to direct now than in my day. I’d have liked to begin making movies today.

Spielberg in fact worked with the 1960s equivalent of a camera phone, Super 8 film, on which he made a number of shorts and even a feature, Firelight. He also had a preternatural grasp of film technique and grammar and uncanny insight into the culture of his time, skills that made him one of the most successful directors of our time. The problem with his YouTube argument is that while almost anyone can make a movie, not everyone has the same abilities. And finding an audience can be overwhelmingly difficult.

Nurturing and mentoring young filmmakers is one of the goals behind the Tribeca Film Institute’s many development programs. The TFI Documentary Fund provided $150,000 in grants to filmmakers like Daniel Gordon (whose The Race examines a disputed contest in the 1988 Seoul Olympics) and Penny Lane and Brian Frye, who use the President’s home movies to provide a new look at Our Nixon.

The Tribeca Film Festival also offers the following programs. The Gucci Tribeca Documentary Fund helps filmmakers complete feature-length documentaries with social justice themes. Tribeca All Access pairs new filmmakers with established professionals for intensive workshops and one-on-one meetings. The TFI New Media Fund offers grants to projects that integrate film with other media platforms. One especially intriguing TFI program involves teaching digital storytelling to immigrant students. In Los Angeles, experienced filmmakers team with teachers, community activists and parents to help students script their own stories in an 18-week program. The program has been operating for six years in all five of New York City’s boroughs. This year, for example, a Bronx school will partner with one in Brazil to make a film.

The Sundance Institute offers several programs as well, including the Sundance Institute Documentary Fund, which gives up to $2 million in grants to between 35-50 documentary projects a year; Stories of Change: Social Entrepreneurship in Focus Through Documentary, a $3 million partnership between the Sundance Institute Documentary Film Program and the Skoll Foundation; and invitation-only Creative Documentary Labs.

Unwilling to tailor your film to fit the rules and regulations of grant organizations? Kickstarter allows you to reach out to peers for financing. The “world’s largest funding platform for creative projects,” Kickstarter currently lists 2715 documentary projects, including films about David Lynch, Simone Weil, and the Oscar-nominated short Incident in New Baghdad.

Girl Walk // All Day is a perfect example of a Kickstarter project. A 77-minute dance video synched to the 2010 album All Day by Girl Talk (sampling artist Gregg Gillis), the project received almost $25,000 from over 500 donors. It’s hard to see how director, editor, and co-cinematographer Jacob Krupnick would have received funding from traditional documentary organizations, but his movie has already been compared to the 3D dance film Pina by Variety. Because of rights issues, it’s unlikely that the film will get a commercial release, but you can screen it online.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/daniel-eagan-240.jpg)