Tropical Storm Sandy Could Bring Extreme Weather to the East Coast for Halloween

A nascent hurricane in the Caribbean could bring flooding and high winds to the East Coast—or could take a turn and head out to sea

![]()

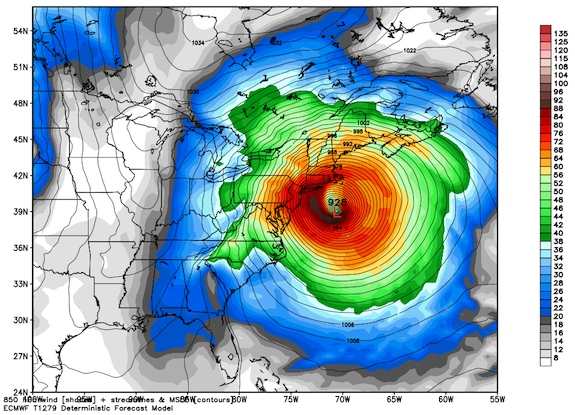

Some models project that tropical storm Sandy could bring extremely high winds and heavy rain to the Northeast early next week. Image via Weatherbell

Update: As of Wednesday at noon, Sandy’s winds have reached 80 miles per hour, leading to it being officially upgraded to a hurricane as is nears Jamaica. Brian McNoldy at the Capital Weather Gang now says that the “odds of an East Coast impact grow,” as an increasing number of models show it turning towards the East Coast after passing by the Carolinas. He notes that one particularly ominous projection “places an incredibly strong cyclone off the New Jersey coast on Monday evening…with tropical storm to hurricane force winds covering every state between Virginia and Maine…A scenario such as this would be devastating: a huge area with destructive winds, extensive inland flooding, possibly heavy snow on the west side, and severe coastal flooding and erosion.”

Tropical storm Sandy is now moving slowly northward across the Caribbean, steadily absorbing warm ocean water and gathering strength. The storm was only identified as a tropical depression on Monday morning, but it’s already been upgraded to a tropical storm and current projections indicate that it will become a hurricane sometime this morning as it crosses over the island of Jamaica.

Meteorologists predict that, over the next two days, Sandy will bring at least ten inches of rain and winds as high as 50 mph to Jamaica, then hit Cuba, Haiti, the Bahamas and Southeast Florida. After the storm crosses these areas and moves up the East Coast, it could bring some truly extreme late-October weather to the Northeast Corridor next week, just in time for Halloween.

“Think if a hurricane and nor’easter mated, possibly spawning a very rare and powerful hybrid storm, slamming into the Boston-to-Washington corridor early next week, with rain, inland snow, damaging winds and potential storm surge flooding,” Andrew Freedman writes at Climate Central. “It could become an extremely large and potent subtropical/extratropical cyclone with the capability of bringing damaging winds and heavy rain (and snow??) well inland, and significant storm surge and beach erosion all along the entire eastern seaboard,” Brian McNoldy writes at the Washington Post‘s Capital Weather Gang blog.

Of course, the most sophisticated projections can’t say for sure what Sandy will do, since we’re talking about the way a storm will behave six or seven days from now. But it’s a testament to the proficiency of short-term weather modeling programs that we’re even able to predict which paths a storm that’s still 1,500 miles away and south of Jamaica could take.

Weather models—the main tools used to produce the forecasts you read or see on a daily basis—work by representing the complex interactions between temperature, wind, water, pressure and other variables in the earth’s atmosphere as a series of mathematical equations. In the models, the atmosphere is sliced into a layered grid with regularly spaced lines, with current data for each of these variables collected and inputted for every box in the grid.

The predictive power of these models is built on historical data collected for each of these parameters. To develop more and more accurate models, researchers assimilate this data, enabling the systems to use previous weather behavior to create equations that are helpful in predicting how weather in the future. Supercomputers then run simulations with slightly different parameters over and over again, making billions of calculations to create a range of possibilities.

The uncertainty in predicting the behavior of this week’s storm lies in the fact that on previous occasions, storms that look like Sandy have generally taken two different paths. In some cases, after moving slightly out to sea east of North Carolina, they have been caught in the jet stream and flung northwest into the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast regions. Such a scenario would lead to the heavy amounts of rain and strong winds described above. In other instances, though, similar storms have simply been dragged eastward out into the Atlantic, which would mean relatively little impact for the East Coast.

An ensemble of different models’ projections for Sandy, showing scenarios in which it hits the Northeast and others where it goes out to sea. Image via National Weather Service

Predicting which of these possibilities will happen is complicated by the fact that, early next week, the jet stream is projected to be carrying unseasonably cold air, a scenario that could affect how it interacts with the storm—and one that we haven’t seen often before. “What could happen is quite complicated and may have precedence only a handful of times across the more than 200 years of detailed historical local weather recordkeeping (Big storms in 1804, 1841, 1991, and 2007 come immediately to mind),” Eric Holthaus wrote in the Wall Street Journal. The 1991 storm became known as “The Perfect Storm” or “The Halloween Nor’easter,” as cold air moving down from the Arctic collided with a late-stage hurricane to cause rain, snow and flooding across the Northeast.

At this stage, experts are still uncertain if we’ll get a perfect storm or a near-miss next week. On Monday, Jason Samenow at the Capital Weather Gang put the odds at 50 percent that the storm will affect some part of the Eastern seaboard and a 20 percent chance of hitting Washington, D.C. in particular; Holthaus at the Wall Street Journal gave it the same odds of hitting New York City.

Because the certainty of weather models increases dramatically within a five-day window, we should have a better idea of what’s going to happen tomorrow or Friday. Until then, we’ll have to wait and see.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)