Baby Sand Tiger Sharks Devour Their Siblings While Still in the Womb

This seemingly horrific reproduction strategy may be a way for females to better control which males sire her offspring

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Surprising-Science-Sand-Sharks-631.jpg)

Baby animals may seem irresistibly adorable, but in reality many of them are calculating killers. Hyena, wolf or even dog litter runts are pushed aside by their larger siblings and left to go hungry; fuzzy white egret chicks will kick their weaker clutch mates out of the nest to certain doom; and baby golden eagles sometimes go so far as to snack on their smaller brothers and sisters while their mother looks on.

Perhaps most disturbing of all, however, is the case of the baby sand tiger shark. While sharks may not be the most snuggly animals to begin with, the sand tiger shark sets a new precedent for fratricide. This species practices a form of sibling-killing called intrauterine cannibalization. Yes, “intrauterine” refers to embryos in the uterus. Sand tiger sharks eat their brothers and sisters while still in the womb.

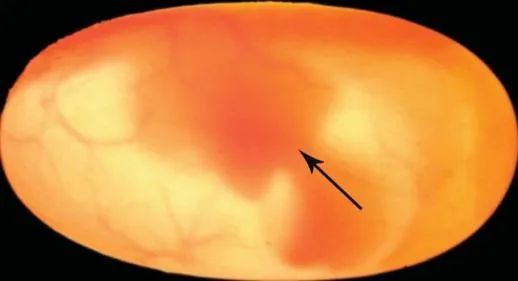

Even by nature’s cruel standards, scientists admit that this is an unusual mode of survival. When sand tiger sharks develop in their mother’s uteri (females have both a left and right uterus), some–usually the embryo that hatched first from its encapsulated, fertilized egg–inevitably grow faster and larger than others. Once the largest embryos cross a certain size threshold, the hungry babies turn to their smaller siblings as convenient meals. “The approximately 100 mm hatchling proceeds to attack, kill and eventually consume all of its younger siblings, achieving exponential growth over this period,” a team of researchers who investigated the phenomenon wrote this week in Biology Letters.

From what began as two uteri full of a dozen embryos results in just two dominating baby sand tiger sharks coming full term. What’s more, once the unborn babies consume all of the living embryos, they turn to their mother’s unfertilized eggs next, in a phenomenon called oophagy, or egg-eating. By the time those two surviving babies are finally ready to be introduced into the big, bright world, all of the pre-birth inner feasting has paid off. They emerge from their mother measuring in at about 95 to 125 centimeters long, or a bit longer than a baseball bat, meaning fewer predators can pick them off than if they had shared food with siblings and were smaller.

This peculiar situation has implications for the genetic makeup of the species. Female sand tiger sharks, like many animals, mate with multiple males. Oftentimes in nature, females determine which males will sire the next generation by selectively choosing to mate with the most impressive bachelor (or bachelors) around. If mating with multiple males at any given time–as sharks, insects, dogs, cats and many other animals sometimes do–the babies that the female eventually produces share the same womb with siblings that may have different fathers.

In this case, however, there are two modes of selection at work. Females may choose mates, but that does not guarantee those males’ genes will make the cut. The embryos the males sire will also have to survive the subsequent frenzy of cannibalism going on inside the female’s body.

To find out whether some males are mating but missing out on actually producing offspring, the authors of this new study undertook microsatellite DNA profiling of 15 sand tiger shark mothers and their offspring. The researchers collected the sharks from accidental mortality events near protected beaches in South Africa between 2007 to 2012. By comparing the embryo genetics, the researchers could determine how many fathers were involved in fertilizing the eggs.

Nine of the females, or 60 percent, had mated with more than one male, the researchers found. When it came to which embryos hatched and grew large first (and thus would have survived if their mothers hadn’t have been killed), 60 percent shared the same father. This means that even if a female mates with more than one male, there is no guarantee that the male has been successful in passing on his genes. Rather, he could have just provided a convenient entree for another male’s offspring.

This also explains some male sand tiger shark behavior and physiology. Male sand tiger sharks often guard their mates against other males just after copulation. Males of this species also produce a conspicuously large amount of sperm compared to other sharks. Both of these characteristics increase the likelihood that the embryo fertilized by that male will successfully implant in the female’s uterus earlier, giving it a significant head start for developing more quickly than its siblings, which makes it more likely that the recent mate’s offspring will eat the others that may come along.

As for the females sand tiger sharks, some researchers think they actually may not have much of a choice when it comes to mating with multiple males. It could be that females just give in to some amorous partners because the energetic cost of resisting those advances outweighs the cost of just conceding to the act–a behavior biologists call the convenience polyandry hypothesis. In this case, however, females may still get the final laugh since the males they first mated with and most likely preferred will have the greater chance of actually triumphing as the father of their children. “ may allow female sand tigers to engage in convenience polyandry after mating with preferred males without actually investing in embryos from these superfluous copulations,” the researchers speculate.

While the females did invest in initially developing those doomed embryos, those investments are much smaller than what would be required to bring multiple embryos to full term. Those smaller embryos also represent resources allocated to the stronger, dominate embryonic winners, which thus have a better chance of surviving and passing on their mother’s genes than if she had spent the energy to instead birth multiple, weakling babies. In a way, the mother shark is providing nourishment for her strongest babies by producing multiple embryos that the most robust can eat.

“This system highlights that competition and sexual selection can still occur after fertilization,” the authors write. For example, the first embryo to implant may not end up being the the one that survives the gladiator arena of the sharks uterus. While this new research still needs to delve into the details of the competition that takes place within the uterus, a picture is emerging based upon these initial findings: Females may chose which males to mate with or may be coerced into reluctantly mating, but male sperm fitness and the quality of the embryos they produce could also carry significant weight in which animals ultimately wind up as winners in this system.

“This competition can play an important and probably under-appreciated role in determining male fitness,” the authors conclude.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)