How to Travel to Outer Space Without Spending Millions of Dollars

Who’s in the space suit? Increasingly, it is our digital selves

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130409010207Youinspace-small.jpg)

Ever since the collective “YOU” became Time Magazine’s Person of the Year in 2006, campaigns to get our attention have increasingly sought out our digital selves. You can name a Budweiser Clydesdale. You can pick Lays’ new potato chip flavor. And it’s not just retail that wants your online opinions: You can vote for who will win photography contests. You can play the futures market on who will win elected offices. And with enough signatures, you can get the White House to read your petitions.

Many science endeavors rely on such crowdsourcing. With a simple app, you can let researchers know the exact date that your lilacs or dogwoods bloom, helping them to track how seasonal cycles are shifting as a result of climate change. You can join the search for ever-larger prime numbers. You can even help scientists scan radio waves in space to search for intelligent life outside of Earth. These more traditional crowdsourcing efforts allow users to brainstorm ideas and process data from computers at home.

But now, a few projects are allowing us to put our virtual selves beyond Earth’s atmosphere through recently launched space missions. Who said that rovers, space probes, a handful of astronauts and pigs were the only ones in space? No longer are we just bystanders watching spacecraft launch and cooing over images returned of other planets and stars. Now, we can direct cameras, help run experiments, even send our avatars–of sorts–to inhabit nearby planetary bodies or return to us in a time capsule.

Here are a few examples:

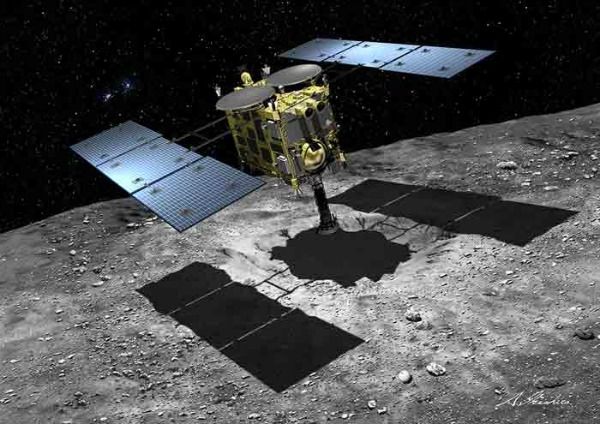

Asteroid Chimney Rock: On April 10 (tomorrow), the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency will open up a campaign that allows visitors to their site the opportunity of sending their names and brief messages to the near-Earth asteroid (162173) 1999 JU3. Called the “Let’s meet with Le Petit Prince! Million Campaign 2,” the effort aims to get people’s names onto the Hayabusa2 mission, which will likely launch in 2014 to study the asteroid. When Hayabusa 2 lands on the asteroid, the names submitted–embedded in a plaque of sorts on the spacecraft–will stand as a testament to the idea that humans (or at least their robotic representatives) were there.

The campaign is reminiscent of how NASA got more than 1.2 million people to submit their names and signatures, which were then etched on two dime-sized microchips and affixed to the Mars Curiosity rover. Sure, it’s a bit gimmicky–what useful function is brought by having people’s names out in space? But the idea of “tagging” a planet or an asteroid–preserving a bit of yourself on what will over decades become space junk–has powerful pull. It is why Chimney Rock, with its etchings from early explorers and pioneers, is the historical marker it is today, and why gladiators scored their names into the Colosseum before they fought to the death. For mission leaders hoping to get the public enthusiastic about space, nothing’s more exciting than a bit of digital graffiti.

Interplanetary time capsules: A key goal of Hayabusa2 is to return return a sample from the asteroid in 2020. Mission creators saw this as a perfect way to get the public to fill a time capsule. Those seeking to participate are encouraged to send to mission coordinators their thoughts and dreams for the future along with their hopes and expectations for recovery from natural disasters, the latter likely a way to get people to express their feelings on the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami that devastated Japan’s east coast. Names, messages, and illustrations will loaded onto a microchip that will not only touch down on the asteroid’s surface, but will also be a part of the probe sent back to Earth with asteroid dust.

But why stop at a mere 6-year time capsule? The European Space Agency, UNESCO, and other partners are blending crowd sourcing with space technology to create the KEO mission–so named because the letters represent common sounds across all of Earth’s languages–which will bundle thoughts and images of anyone who seeks to participate and will launch this bundle in a probe that will only return to Earth in 50,000 years.

Project operators write on KEO’s website: “Each one of us have 4 uncensored pages at our disposal: an identical space of equality and freedom of expression where we can voice our aspirations and our revolts, where we can reveal our deepest fears and our strongest beliefs, where we can relate our lives to our faraway great grandchildren, thus allowing them to witness our times.” That’s 4 pages for every person who chooses to participate.

On board will be photographs detailing Earth’s cultural richness, human blood encased in a diamond, and a durable DVD of humanity’s crowdsourced thoughts. The idea is to launch the time capsule from an Ariane 5 rocket into an orbit more than 2,000 kilometers above Earth, hopefully sometime in 2014. “50,000 years ago, Man created art thus showing his capacity for symbolic abstraction.” the website notes. And in another 50,000 years, “Will Earth still give life? Will human beings still be recognizable as such?”Another logical question: Will whatever’s left on Earth know what’s coming back to them and will be able to retrieve it?

Hayabusa2 and KEO will join capsules already launched into space on Pioneer 10 and 11 and Voyager 1 and 2. But the contents of these earlier capsules were picked by a handful of people; here, we get to choose what represents us in space, and will get to reflect (in theory) on the thoughts bound in time upon their return.

You, the mission controller and scientist: Short of going to Mars yourself, you can do the next best thing–tell an instrument currently observing Mars where to look. On NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter is the University of Arizona’s High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE), a camera designed to image Mars in great detail. Dubbed “the people’s camera,” HiRISE allows you–yes, you!– to pick its next targets by filling out a form specifying your “HiWishes."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mohi-kumar-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mohi-kumar-240.jpg)