Evidence for the Oldest Ever Bone Tumor Was Just Found in a Neanderthal Fossil

A 120,000-year-old rib bone, originally found in Croatia, shows that tumors aren’t always caused by exposure to pollution

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bf/cb/bfcb190c-07c0-42f0-9bf7-ae28503a0790/tumor.jpg)

Some 120,000 years ago, in the hills of what is now Northern Croatia, an adult Neanderthal took his or her last breath. We don’t know much about this Neanderthal—his or her sex, exact age, or even what he or she died from—but new research has revealed something rather interesting present in his or her skeleton. Specifically, in the upper left rib.

As a team of researchers from the University of Pennsylvania and the Croatian National History Museum recently discovered, this Neanderthal had a tumor indicative of a disease called fibrous dysplasia—a condition in which normal bone is replaced by a fibrous, spongy tissue. Tumors of any kind are extremely rare in the human fossil record, and previously, the oldest bone tumors ever discovered were a mere 1,000–4,000 years old.

As a result, the researchers write in an article published today in PLOS ONE, “The tumor predates other evidence for these kinds of tumor by well over 100,000 years.”

The rib bone that the team analyzed was originally excavated from a site called Krapina, a Croatian rock shelter that, in the late 1800s, was found to contain 876 Neanderthal fossil fragments that belonged to several dozen individuals who’d all died around 120,000 to 130,000 years ago. Scientists have proposed a range of theories to account for why the fossils are so fragmented: Some have argued that the broken and charred remains are evidence of cannibalism, while others speculate that the Neanderthals were killed and eaten by carnivorous animals.

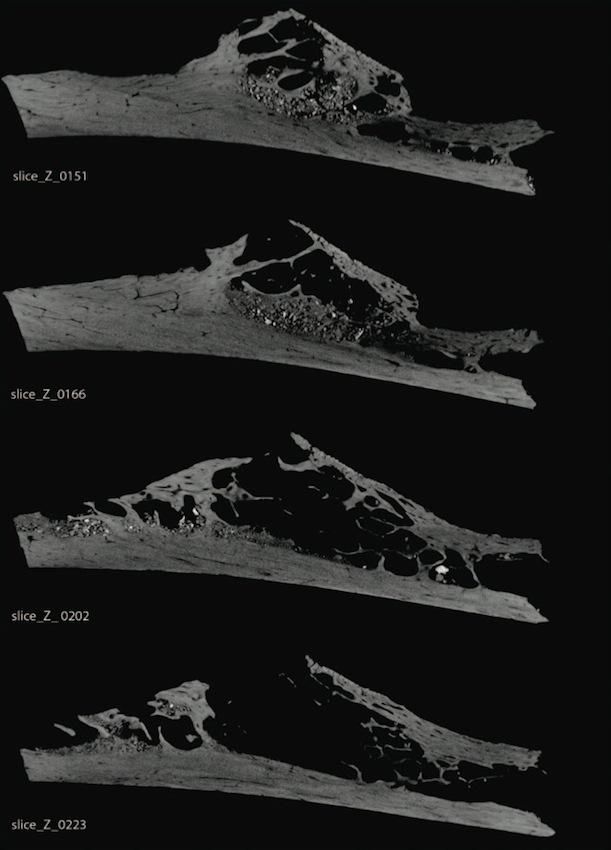

The rib found in this bone heap is fractured and can’t be definitively paired with any other remains, but the researchers believe it matches with a right rib found nearby at the site. The first-ever detailed analysis of the bone, which included X-ray and CT scanning (right), showed a rather large lesion located at the center, which was left behind by a tumor characteristic of fibrous dysplasia. The researchers ruled out the possibility that the cavity was simply caused by a fracture because there is no evidence of trauma elsewhere on the rib—the lesion protrudes out towards the front of the bone, so if it were caused by a fracture, trauma would be visible on the back side of it.

In some cases, fibrous dysplasia causes no symptoms, while in others, the swelling produced by the tumors can cause deformity. But without the full skeleton, there’s no way of knowing what the overall effect of the disease was on the individual and whether he or she died as a result or due to entirely unrelated causes.

In either case, though, this discovery is valuable for a simple reason: Tumors, on the whole, are extremely rare in the hominid fossil record. When they occur in any tissue apart from bone, they’re unlikely to be preserved, and they also tend to develop during middle age and onwards. Because our ancient ancestors (or—in the case of Neanderthals—cousins) typically didn’t live past their thirties, they probably developed few cases of cancer or benign tumors.

However, this find shows that Neanderthals did develop this type of tumor, which tells us something about the underlying disease. The frequency of many kinds of tumors, both cancerous and benign, are generally thought to correlate with pollutants in the environment. But as the researchers note, the environment that these Neanderthals lived in was essentially pristine—meaning that, at least in some cases, the development of bone tumors has nothing to do with environmental pollution.

This discovery is part of a larger, emerging trend in which scientists are learning about the ancient history of diseases through the fossil record. Last year, analysis of the DNA extracted from hominid teeth and skulls showed that many of the viruses that infect modern humans also lived in Neanderthals and other hominids, and in February, DNA extracted from ancient human teeth helped scientists understand the evolution of oral bacteria over time.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)