This Bumpy-Faced Reptile Ruled the Prehistoric Desert

Newly excavated fossils tell us more about the cow-sized, plant-eating Bunostegos akokanensis, which roamed Pangea around 260 million years ago

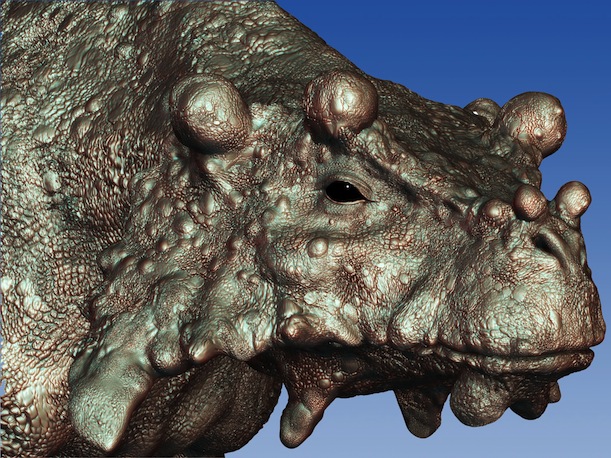

An artist’s rendering of Bunostegos, a plant-eating reptile that lived in the deserts of Pangea some 266 to 252 million years ago. Image via Marc Boulay

If, somehow, you were magically transported back 255 million years in time to the middle of the vast desert that likely lay at the center of the supercontinent Pangea, you might come face to face with a cow-sized reptile called Bunostegos akokanensis. But no need to fear!

Despite its frighteningly bumpy-faced appearance, the creature was a confirmed vegetarian.

Ongoing excavations in Niger and elsewhere in Africa are allowing paleontologists to learn more about the extinct animals that roamed this ancient desert, and several newly discovered Bunostegos skull fossils provides one of the first looks at this admittedly unusual-looking creature. The reptile, described in an article published today in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, truly lives up to the name of its genus: Bunostegos translates literally as knobby skull roof.

One of three Bunostegos skull fossils recently excavated and analyzed. Image via Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Tsuji et. al.

Detailed analysis of the fossils, led by Linda Tsuji of the University of Washington, allowed the researchers to produce a rendering of what the reptile would have looked like alive. At a best guess, the creature’s face was dotted with skin-covered bulbous protrusions, similar to the bumps on a giraffe’s head. “Imagine a cow-sized, plant-eating reptile with a knobby skull and bony armor down its back,” Tsuji said in a press statement, describing the creature.

The reptile belongs to the Pareiasaur group, made up of relatively large herbivores that lived during the Permian period, which lasted from 298 to 252 million years ago. Many other Pareisaurs also sported knobs on their heads, though not nearly as large as Bunostegos’. As a result, researchers had previously assumed that Bunostegos was a particularly advanced Pareiasaur, evolutionarily speaking—it had been part of the broader group for its entire evolutionary history and then evolved further.

This new analysis, though, showed that the Bunostegos also retained a number of relatively primitive characteristics—such as the shape and number of its teeth—that were found in older reptiles but not other Pareisaurs. As a result, the researchers conclude that the Bunostegos actually split off from the other creatures in its group much earlier on, and independently evolved the bony knobs on its head.

This sort of analysis also helps researchers make broader conclusions about the environment Bunostegos lived in. If Bunostegos underwent an extended period of independent evolution, there’d need to be some feature of the landscape that prevented members of the species from mingling and interbreeding with closely related reptiles in the meantime.

That feature, the researchers say, is a long-speculated enormous desert at the center of Pangea. Geological evidence supports the idea that the area—located in what is now Central and Northern Africa—was extremely dry during the late Permian, 266 to 252 million years ago, and other fossils found there show patterns of speciation that suggest long-term isolation.

Sometime soon after this period, though, Bunostegos—along with most Pareisaurs as a whole and 83% of all genera—were lost in a mass extinction event due to reasons we still don’t fully understand. Some scientists, though, believe that modern-day turtles are the direct descendants of Pareisaurs—so learning more about the anatomy and evolutionary history of this group of reptiles could help us better understand the diversity of life currently on our planet.

The key to finding out more, they say, is simple: keep digging. “It is important to continue research in these under-explored areas,” Tsuji said in the statement. “The study of fossils from places like northern Niger paints a more comprehensive picture of the ecosystem during the Permian era.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)