Waters Around Antarctica May Preserve Wooden Shipwrecks for Centuries

Some capsized ships may linger on the ocean floor indefinitely

“The Sphinx of the Ice Fields” or “An Antarctic Mystery,” drawn in 1895. Photo by George Roux

Maritime lore is rich in our culture–think stories of pirates hoarding priceless plunder, of monster whales and squid pulling ships into a watery doom, of sailors singing sea shanties as they work. But for ocean dreamers of all ages, nothing is more mysterious and tantalizing as a shipwreck, with its shared promise of bounty, history and horror. While many search from stem to stern for stems and sterns in tropical, temperate and Arctic waters, new research supports the idea that they’d have better luck venturing far, far south.

That’s because in more northerly waters, bottom-dwelling creatures that scavenge the ocean floor for nutrients aren’t picky in the least–they’ll feast upon a wooden shipwreck as enthusiastically as a deceased whale. But as seen in a study published today in journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Science, deep-sea animals on the dark and frigid ocean floor surrounding Antarctica won’t just eat any scrap of potential food that drifts their way. In those southerly waters, bone alone is the delicacy of choice for the wormy detritivores that lurk on the ocean floor. Because wood is shunned by those munchers of decay, shipwrecks surrounding Antarctica may linger on for decades or even centuries in remarkably well-preserved conditions.

Normally, any bit of organic debris–whether a sunken log or a deceased creature–will quickly become an island of teeming activity for scavenging creatures on the ocean floor. Researchers tend to break these creatures down into two groups: bone-eating (Osedax) and wood-eating (Xylophaga) worms. Though both groups of organisms share similarities in the way they bore into their food sources and disperse through the environment, each is specialized to feast upon either plant or animal material. These worms pop up in oceans around the world, but no one had taken the time to investigate their presence–or lack thereof–in Antarctica.

An international team of researchers decided to tackle this question. In the case of Antarctica, the team knew that trees had not grown on the frozen continent for around 30 million years. And because of strong currents surrounding the continent, wood likely would not wash into those waters from other locations. Since humans began exploring Antarctica, however, they’ve dumped wood overboard as garbage, or lost wooden ships (along with their lives) to wrecks.

At the same time, many species of whale pass through or live around Antarctica, providing plenty of opportunities for whale-falls, or deceased giants, to wind up on the ocean floor.

Because of these historic differences, the rate of decay for the wood would likely be less than that for the bone, the researchers hypothesized, since wood-eating worms would not be naturally present there. Even though ample wood food sources now litter the ocean floor, the team further guessed, the strong Antarctic currents bar wood-eating worms in more northern waters from venturing south.

To find out if their hunches were correct, the scientists conducted a simple experiment at three ocean sites, each about 1,600 feet deep, around Antarctica. They lowered bundles of whale bones mixed with oak and pine planks. They left those bundles to rot on the ocean floor for 14 months.

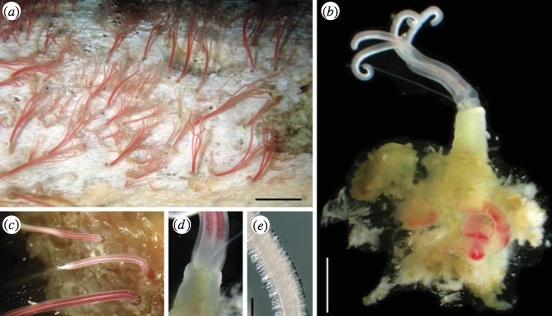

Some of the specimens recovered by the researchers include a) bone-eating worms emerging from a bone fragment. A closeup of a bone-eating worm extracted from the whale bone is seen in b); c) d) e) show closeups of the bone-eating worms palps, or mouth parts, which they use for feeding and sensing the surrounding environment. Image by Glover et al., Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences

After they recovered the wood and bone from the sea floor, they collected all the animals attached to the bone and wood, and identified which species they belonged to. The wood, they found, was in “pristine condition,” with only a few jellyfish larvae attached to it, but no animals boring into it. The whale bone, on the other hand, came back heavily infested with bone-eating worms. “Every whale bone recovered…was covered in a thick pink-colored ‘pelt’ of Osedax,” the team reports. “On a single rib bone, a density of 202 specimens per 100 was recorded.” Indeed, the team even found two new species of bone-eating worms attached to their bone specimens.

These findings, they write, confirm that bone-eating worms are abundant in Antarctica, but that wood-eating ones are conspicuously absent. This has implications for marine archeologists interested in investigating historic shipwrecks, such as Ernest Shackleton’s pine and oak ship Endurance, which sunk on an expedition in 1914 and has not yet been found. Further, traveling around South America’s Cape Horn was the only sea route from the Atlantic to Pacific oceans prior to 1914–the rough seas and numerous iceberg found there that made that region a sailor’s graveyard now make it a prime candidate for finding shipwrecks. Such ships are likely kept in exceptionally good condition thanks to the absence of animals that would normally facilitate their decay.

But the presence of this wood does have its drawbacks–wood that last for centuries on the ocean floor may leach the chemicals used to treat it or crowd out natural habitats, thus becoming a significant source of pollution. And if climate change affects the strength or location of ocean currents, or if wood-eating worms find some other way into the environment, the worms could become an invasive species, the team points out.

For now, however, wood that found its way to the Antarctic ocean floor seems there to stay. Let the treasure hunts begin!

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)