The Past and Future of the Baseball Bat

The evolution of the baseball bat, and a few unusual mutations

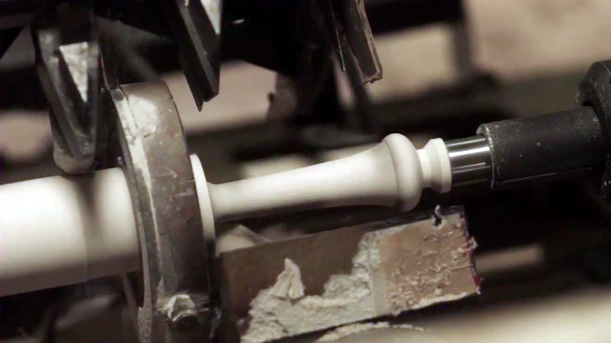

An inside look at how a Louisville Slugger is made.

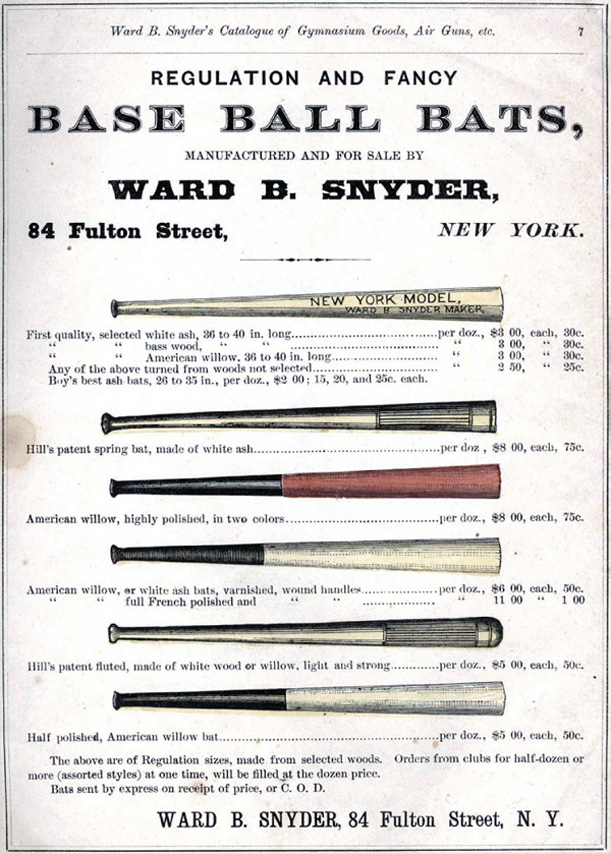

By the 1860s, there were almost as many types as baseball bats as there were baseballs. And like early pitchers, who made their own balls, early batters were known to sometimes whittle bats to suit their own hitting style. As you might imagine, the results were quite diverse—there were flat bats, round bats, short bats and fat bats. Generally, early bats tended to be much larger and much heavier than today’s. The thinking was that the bigger the bat, the more mass behind the swing, the bigger the hit. And without any formal rules in place to limit the size and weight of the bat, it wasn’t unusual to see bats that were up to 42 inches long (compared to today’s professional standards of 32-34) with a weight that topped out at around 50 ounces (compared to today’s 30).

While bats made of ash have always been a popular choice, maple, willow and pine were also commonly used, and it wasn’t unheard of to see spruce, cherry, chestnut and sycamore. Basically, if it could be chopped down, it could be a bat. After a couple decades of natural selection, round, ash bats had become the preferred choice. From the 1870s onward, ash continued to be the most popular for major league batters until Barry Bonds picked up a maple bat and started breaking records. Other batters soon followed his lead, despite the fact that a test conducted by the Baseball Research Center in 2005 concluded that “maple has no advantage in getting a longer hit over an ash bat.”

By 1870, bat regulations were in place limiting the length of the bat to 42 inches and the max diameter to 2.5 inches. This is more or less the standard today, as defined in the MLB rulebook:

1.10

(a) The bat shall be a smooth, round stick not more than 2.61 inches in diameter at the thickest part and not more than 42 inches in length. The bat shall be one piece of solid wood.

Top: Louisville Slugger’s MLB Prime Ash bat. Ash is lighter than maple but gives players a larger sweet spot and is less likely to break. Bottom: Louisville Slugger’s MLB Prime Maple. Maple bats are hard, built for power, produce a satisfying crack that will echo up to the cheap seats, and are more likely to turn into kindling.

In 1884, the most famous name in baseball bats made its debut when 17-year-old John A. “Bud” Hillerich took a break from his father’s woodworking shop in Louisville, Kentucky, to slip away and catch a Louisville Eclipse game. When the team’s slumping star Pete Browning broke his bat, the young Hillerich offered to make him a new one. Bud made a new bat to Browning’s specifications, and the next game, the star of the Louisville Eclipse broke out of his slump, shining brightly once again, and the Louisville Slugger was born. Word spread about Hillerich’s bat and soon other major leaguers wanted one too. However, Hillerich’s father was reluctant to take on the new business. He was convinced that his company’s future would be built on architectural details such as stair railings, balustrades and columns; he saw bats as little more than a novelty item. With the particular brand of certainty and naiveté that is unique to the young, Bud persisted, eventually convincing his father that baseball was good business. By 1923, Louisville Slugger was the country’s top manufacturer of baseball bats.

Top: A vintage reproduction of a circa 1906 “mushroom” bat, designed to provide a counterweight to the early heavy bats that could weigh up to 50 oz. Bottom: Vintage reproduction of a “Lajoie” bat designed by Napoleon “Nap” Lajoie.

While the bat hasn’t changed dramatically since the late 19th century, there are a few short-lived oddities and attempts to improve on the design, like the “mushroom” bat from Spalding and the Lajoie (above), designed by Ty Cobb rival Napoleon Lajoie and said to offer a better grip and improve bat control. And then there’s this incredibly strange design, patented in 1906 by Emile Kinst:

Patent No. 430,388 (June 17, 1890) awarded to Emile Kinst for an “improved ball-bat.” In his patent, Kinst wrote: “The object of my invention is to provide a ball-bat which shall produce a rotary or spinning motion of the ball in its flight to a higher degree than is possible with any present known form of ball-bat, and thus to make it more difficult to catch the ball, or if caught, to hold it, and thus further to modify the conditions of the game….”

And yes, some of these “banana bats” were actually made:

This kind may even have been used by minor league players, but by the dawn of the 20th century, restrictions on the bat were firmly in place.

All these innovations were developed to aid in hitting. More recently though, the bat was redesigned to aid the hitter.

During the dead-ball era, baseball players used to grip the bat differently, holding it further up the grip. The knob at the end was to keep players’ hands from sliding off the bat. But in the modern game, players hold the bat with their hands as low as possible—sometimes even covering the knob. Graphic designer Grady Phelan created the Pro-XR bat in response to the modern grip.

The major innovation on the Pro-XR bat is the new ergonomic knob, slanted to ensures the batter’s hand doesn’t rub against it. The design reduces injury, as well as the chances that a bat will be thrown by preventing the hand’s ulnar nerve from sending a “release” signal to the brain. Limited testing suggests that the bat will reduce pressure on the hand by 20 percent. It has been approved by the MLB and is currently used in play. But despite the major benefits it offers, baseball players are a stubborn and superstitious lot, and it’s unlikely that the Pro-XR will become the league’s go-to bat—unless someone starts breaking new records with it.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)