The History of Baseball Stadium Nachos

From a Mexican maitre ‘d’s mishap in 1943 to the gooey, orange stuff you put on your chips at the baseball game today.

A Ricos advertisement for the nacho bowl from the early ’80s. Image courtesy of Ricos Products Co., Inc.

The smell of freshly cut grass, the crack of the bat, the 30 minutes standing in line at the concession stand. Baseball season is up and running and the experience of going to a game wouldn’t be the same without an expensive beer in one hand and a plastic receptacle of nachos covered in ooey-gooey cheese product in the other. But how did nachos become a stadium standard?

In September 1988, Adriana P. Orr, a researcher at the Oxford English Dictionary, was asked to trace the etymology of the word “nachos” and conducted an initial investigation of the nacho story. She followed a paper trail of documents and newspaper articles until she found what she was looking for in the Hispanic Division of the Library of Congress:

“As I walked down the long corridor leading back to the library’s central core, I heard a voice softly calling my name. There was a young woman I recognized as a staff member of the Hispanic Division…she told me she had been born and raised in Mexico and there, nacho has only one common usage: it is the word used as a diminutive for a little boy who had been baptized Ignacio. His family and friends call him Nacho… Now I was convinced there was a real Nacho somewhere who had dreamed up a combination of tortilla pieces with melted cheese and jalapeño peppers.”

Using this information, Orr tracked down a quote from the elusive 1954 St Anne’s Cookbook printed by The Church of the Redeemer, Eagle Pass, Texas, which includes a recipe for a dish called “Nachos Especiales.”

What Orr would find is that, in 1943 in Piedras Negras, Mexico — just across the border from Eagle Pass, a group of hungry army wives were the first to eat the meal. When the ladies went to a restaurant called the Victory Club, the maitre d’, Ignacio “Nacho” Anaya greeted them. Without a chef around, Anaya threw together whatever food he could find in the kitchen that “consisted of near canapes of tortilla chips, cheese, and jalapeno peppers.” The cheese of choice was reportedly Wisconsin cheddar. Anaya named the dish Nachos Especiales and it caught on—on both sides of the border—and the orignal title was shortened to “nachos.”

Anaya died in 1975, but a bronze plaque was put up in Piedras, Negras, to honour his memory and October 21 was declared the International Day of the Nacho.

If Anaya is the progenitor of nachos especiales, then how did it happen that Frank Liberto came to be known as “The Father of Nachos”? Nachos were already popular at restaurants in Texas by the time Liberto’s recipe hit the scene, but he’s famous in the industry for bringing his version of the dish to the concession stand in 1976 at a Texas Rangers baseball game in Arlington, Texas. What he did that no one else had done before, was create the pump-able consistency of the orangey-gooey goodness we see today—what the company calls “cheese sauce.” Though some versions are Wisconsin cheddar-based like Anaya’s original, according to the company most of the products are blends. (According to the Food and Drug Administration’s standards, the sauce is technically not “cheese,” but that hasn’t stopped fans from pumping it by the gallons since). Liberto’s innovation didn’t need to be refrigerated and had a longer shelf life. His recipe was top secret—so secret that in 1983 a 29-year-old man was arrested for trying to buy trade secrets into Liberto’s formula.

As a concessionaire, transaction time was key—Frank didn’t want customers to wait more than a minute in line for their snack. To meet this demand, he came up with the idea of warming up a can of cheese sauce, ladling it over the chips and then sprinkling jalapeños on top. Frank’s son and current president of Ricos Products Co., Inc., Anthony ‘Tony’ Liberto, was 13 when Ricos introduced the product in Arlington Stadium. He recalls that the concession operators wouldn’t put the cheesy chips in the stands. They were afraid that the new product launch would cannibalize other popular items like popcorn, hotdogs and sodas.

“We had to build our own nacho carts,” Liberto, now 50, says. “My dad has an old VHS tape where people were lined up 20 people deep behind these concession carts. You’d hear the crack of the bat and you’d think that they’d want to see what play was going on, but they stayed in line to get their nachos.”

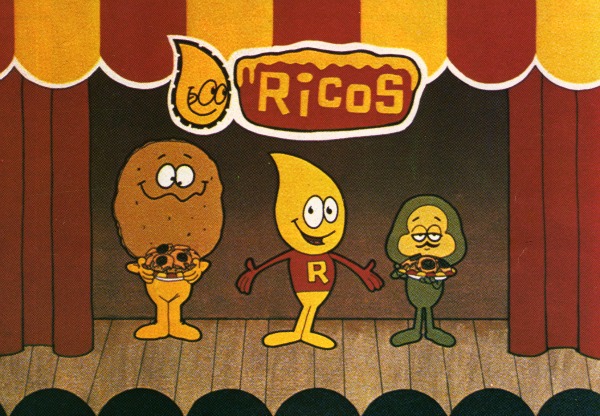

This 35mm film trailer from the ’70s starring Nacho, Rico and Pepe was created by Walt Disney animators and was used during intermission at movie theaters. Image courtesy of Ricos Products Co., Inc.

It was an immediate success: That season Arlington Stadium sold Ricos’ nachos at the rate of one sale per every two-and-a-half patrons—over $800,000 in sales. Popcorn, which previously had the highest sales, only sold to one in 14 patrons for a total of $85,000. There is one ingredient to thank for that shift, Liberto says: The jalapeño pepper.

“When you put a jalapeño pepper on chips and cheese, of course it’s going to be spicy,” he says. “You’re going to start looking for your beverage—a Coke or Pepsi, whatever—you’re gonna need something to drink.”

Beverage sales spiked and hotdog and popcorn sales thereafter, he says. By 1978, the spicy snack became available at the Dallas Cowboys’ stadium, where iconic “Monday Night Football” announcer Howard Cosell would put nachos on the map. Cosell, a household name for football fans, sat alongside Frank Gifford and Don Meredith giving viewers the play-by-play, when a plate of nachos was brought to the broadcast room.

“Cosell was trying to take up some dead air and he says ‘They brought us this new snack—what do they call them? knock-o’s or nachos?’” recalls Liberto. “He started using the word ‘nachos’ in the description of plays: ‘Did you see that run? That was a nacho run!’”

Cosell and others used the word for weeks after, allowing nachos to branch out from their Texas birthplace.

“My father first sold a condensed formulation of the product,” Tony says. “You open up the can, add water or milk and pepper juice to the mix.”

Each number ten can contains 107 ounces of the condensed cheese conconction to which 32 ounces of water and 20 ounces of pepper juice are added. Once combined, the cheese blend is put into a dispenser like the pump or button-operated machines you see at concession stands today.

“That’s an added 52 ounces of servable product,” Tony says. “Nearly 50 percent more sauce Plus, the water is free and the pepper juice you get from the jalapenos anyway. You get an additonal 52 0z to serve and it doesn’t cost the company a dime.”

Just to make this profit thing clear—some math: If you have an extra 52 ounces of product and each two-ounce serving of cheese sauce goes for four bucks a pop, that’s 100 dollars directly into the concessionaire’s cash register.

An advertisement from 1956. The company responsible for stadium nachos surprisingly sells a lot of sno-cone products. Image courtesy of Ricos Products Co., Inc.

Tony has two children, a daughter (13) and a son (11), who he hopes will take an interest in working for the family business one day as he did. His niece, Megan Petri (fifth generation), currently works for Ricos Products Co., Inc.

“We can’t go to any baseball game without getting an order of nachos,” says Liberto. “ says ‘I need my nachos I need my nachos.’ It’s like she needs her fix.”

His daughter is not alone in her affinity for her family’s invention. As millions of people crunch into their plates of chips and cheesiness at baseball games and movie theaters around the world, one question remains: How much cheese is actually in the nacho sauce?

“I will not tell you that,” he laughs. ”We’ve got lots of formulas and that is a a trade secret—you never want to give away how much cheese is in your product.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/561436_10152738164035607_251004960_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/561436_10152738164035607_251004960_n.jpg)