Nearly 8 Miles Down, Bacteria Thrive in the Oceans’ Deepest Trench

The Mariana Trench may serve as a seafloor nutrient trap, supporting remarkable numbers of microorganisms

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Surprising-Science-Sea-Bacteria-631.jpg)

The Challenger Deep, the deepest point on the entire seafloor, lies in the Mariana Trench off the coast of the Pacific Ocean’s Mariana Islands. It is nearly 36,000 feet—7.8 miles—below the ocean’s surface. If you were to stand at this remarkable depth, the column of water above your head would exert 1000 times the amount of pressure you normally experience at the surface, crushing you instantly.

Even in this extreme environment, though, organisms can survive. One type, it turns out, can even prosper: bacteria. A new study, published today in Nature Geoscience, finds that unexpectedly abundant bacteria communities grow in the depths of the Mariana Trench, with organisms living at densities ten times greater than in the much shallower ocean floor at the trench’s rim.

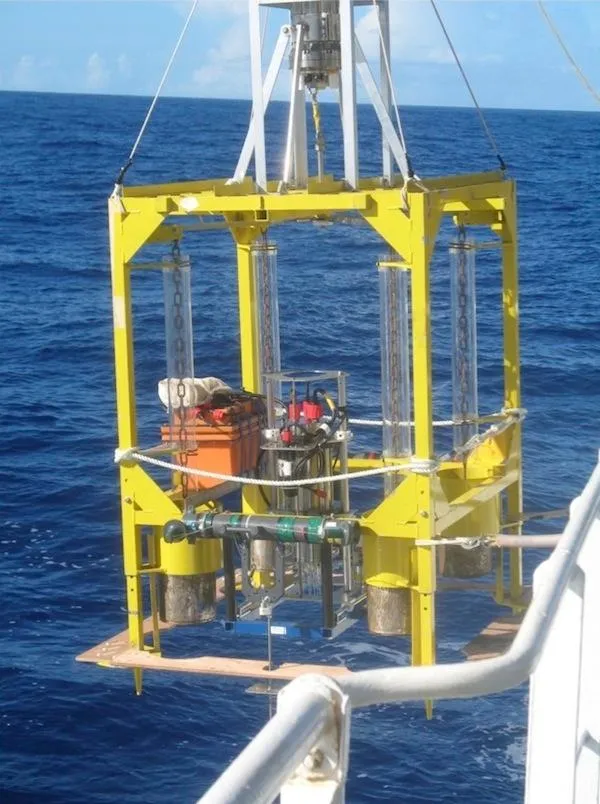

To probe the ultra-deep ecosystem, the international research team, led by Ronnie Glud of the University of Southern Denmark, sent a specially-designed, 1300-pound robot down to the bottom of the trench in 2010. The robot was equipped with thin sensors that can slice into the seafloor sediments to help measure the organic consumption of oxygen. Because living things consume oxygen as they respire, tallies on how much ambient oxygen is missing from the sediments can be used as a proxy for the amount of microorganisms living in that area.

When the team used the device to sample the sediments at a pair of sites with depths of 35,476 and 35,488 feet, they found surprisingly high amounts of oxygen consumption—levels that indicated there were ten times more bacteria present at the ultra-deep site than at another, shallower site they sampled for reference about 37 miles away, at a depth of just 19,626 feet.

The robot also collected a total of 21 sediment cores from the two sites, and these cores were hauled up and analyzed in the lab. Although many of the microorganisms died when they were brought up to the surface—after all, the creatures are adapted for the high pressure and low temperature of the ocean floor—the finding was confirmed: Cores from the Mariana Trench had much higher densities of bacterial cells than those from the reference site.

The team also remotely recorded video of the ocean floor, using lights to illuminate the pitch-black environment, and found a few life forms much larger than bacteria scurrying around on top of the sediment. When they used baited traps to recover a few of the specimens and bring them to the surface, they determined they were Hirondellea gigas, a species of amphipods—small crustaceans typically less than an inch in length.

The discovery of such abundant bacterial life is particularly surprising because conventional wisdom would suggest that not enough nutrients are present at such depths to support much growth. Photosynthetic plankton serve as the nutrient base for nearly any ocean food chain, but they’re unable to survive on the lightless seafloor. The waste products (such as dead animals and microorganisms) of ecosystems higher up in the shallow light-filled waters do filter down and feed deeper food webs, but typically, less and less organic matter makes it down as depths increase.

In this case, though, the scientists seem to have found an exception to the rule, since the ultra-deep trench was home to so much more bacterial activity than the nearby shallower reference site. Their explanation is that the trench acts as a natural sediment trap, gradually collecting nutrients that filter down and land at shallower locations on the ocean floor nearby, then are dislodged by earthquakes or other perturbations.

In the years since the 2010 exploration, the research team has sent the same robot down to sample the Japan Trench (roughly 29,500 feet deep) and plans to sample the Kermadec-Tonga Trench (35,430 feet deep) later this year. “The deep sea trenches are some of the last remaining ‘white spots’ on the world map,” Glud, the lead author, said in a press statement. “We know very little about what is going on down there.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)