Here Are the Treasures Libyan Violence Is Keeping Archaeologists From

Libya’s civil war might be over, but the aftershocks of the revolution are still reverberating through the country

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c3/18/c318724b-3cc2-4738-a75e-4348bd89041e/leptis-magna.jpg)

Libya’s civil war might be over, but the aftershocks of the revolution are still reverberating through the country. Just yesterday there was more violence in the capitol city of Tripoli. The fledgling Libyan government is still trying to wrangle militias and control the flow of arms through the country, with only moderate success.

One group affected by the ongoing unrest: archaeologists. This Nature article from the start of the revolution details why so many of them are interested in Libya: “the country has been a ‘melting pot’ of cultures throughout history, and has sites of Punic and Roman remains to the west, Greek and Egyptian to the east and Berber to the south. There are also important prehistoric sites, including some of the world’s earliest rock and cave art, and underwater archaeological sites along the Mediterranean coast.” Libya has five UNESCO World Heritage sites, including the ruins of Leptis Magna, a massive Roman city almost perfectly preserved.

During the war, scholars from around the world compiled “do not strike” lists of the coordinates of Libyan archaeological sites and handed them over to NATO, which avoided bombing those areas during their air strikes. But now, this wealth of history is now under constant threat of looters and armed skirmishes. British and Italian researchers have been prevented from resuming their fieldwork because of security concerns. Locals near Leptis Magna have taken to patrolling the streets of the ancient ruins, attempting to protect the site. French archaeologists returned in 2012 and are currently working with their Libyan counterparts on excavating the baths at Leptis Magna, but the bombing of the French embassy in April called the long-term feasibility of their mission into question.

The researchers are desperate to get back to work, and with good reason. Here are some of the most amazing sites that remain in Libya’s borders:

Leptis Magna

The birthplace of Roman Emperor Septimus Severus, the site is described as “one of the most beautiful cities of the Roman Empire.” The city didn’t start out as Roman. Originally a Phoenician port, it passed onto the Carthaginians, the Numidians, and eventually to the Romans as power changed hands in North Africa. The power shifting continued until it was conquered by an Arab group, the Hilians, in the 11th century. Soon after, it was abandoned, and slowly covered with drifiting sand until it was re-discovered by archaeologists. Remarkably, it’s artificial port, (built by Nero) is still intact.

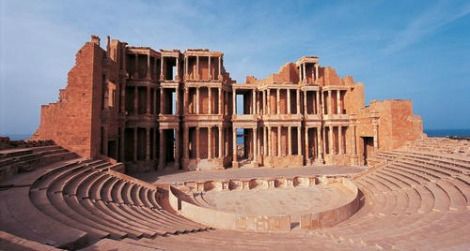

Sabratha

Also starting as a Phoenician port, the city of Sabratha. It was a grand, bustling city, whose most notable feature today is the dramatic remains of the 5,000-seat theatre. It is also renowned, along with Leptis Magna for the mosaics discovered there.

Cyrene

This ancient Greek city is full of ancient temples, statues and a massive necropolis just outside the city limits. It was destroyed and abandoned after a huge earthquake and tidal wave in 365 AD. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

This area of Libya, bordering Algeria, is a mountainous area of the Sahara. It is precious to Archaeologists for the thousands of cave paintings found in the area, some dating back to 12,000 BC, others as recent as 100 AD. The delicate paintings are also under threat from oil excavation techniques in the area. These paintings (many of animals) are an incredible archive of what kinds of plants and wildlife lived in the area thousands of years ago.

From UNESCO:

- during the naturalistic phase, corresponding to the last phase of the Pleistocene epoch (12,000-8000 BC), one sees numerous outline engravings, representing the large mammals of the savannah: elephants, rhinoceros, etc.

- during the round-head phase (c. 8000-4000 BC) engravings and paintings coexisted. The fauna was characteristic of humid climate; magic religious scenes appeared.

- the pastoral phase, from 4000 BC, is the most important in terms of numbers of paintings and engravings; numerous bovine herds are found on the decorated walls of the grottoes and shelters.

- the horse phase, from 1500 BC, is that of a semi-arid climate, which caused the disappearance of certain species and the appearance of the domesticated horse.

- the camel phase (first centuries BC) saw the intensification of a desert climate. The dromedary settled in the region and became the main subject of the last rock-art paintings.

More from Smithsonian.com:

Q+A: How To Save the Arts in Times of War

Swords and Sandals

Should Americans Travel to the Middle East?