Tasting France’s Finest Wines

Sauternes is a village near Bordeaux that would have been cow town if dumb luck, microclimatology and royal wineries had not showered the region in fortune

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120524092050WineSauternesBottleSMALL.jpg)

When I received an invitation from one of the earth’s most prestigious wineries to come and visit the estate, press my face up against the bars and take photos of the property from outside the gate, I wasn’t sure whether to be honored or humiliated.

But I visited Chateau Margaux anyway, in spite of the discouraging email—a response to a tour request I had sent. One of Bordeaux’s top juice-fermenting factories, Chateau Margaux looked roughly like every other winery in the area—a huge and frightening castle-like thing, with hedges and lawns out front, surrounded by stodgy rows of vines, and recognizable, it seemed, from such childhood classics as Beauty and the Beast and Fantasia. I moved on through the pouring rain, all my gear soaked. It was looking possible that I would be camping, shivering wet, in a gas station or bus shelter, until, at 8:30 p.m., I found a hotel in suburban Bordeaux. I generally consider it a disaster when I have to pay another person to sleep, but tonight I could have wanted nothing more.

I draped the walls with my wet clothes and got cleaned up for the next day—for I had a tour and tasting arranged at Chateau d’Yquem. A producer, most notably, of a white regional dessert wine called Sauternes, Chateau d’Yquem is located about 30 miles south of Bordeaux near the Ciron River and was a favorite winery of Thomas Jefferson. Today, its wines are among the most reputed in the world; a mini bottle of the 2008, for example, goes for about $200, and a full-sized bottle can be bought for somewhere in the neighborhood of $600. Some aged specimens cost about 150 round-trip tickets from San Francisco to Paris, and the real trophies of the past are basically priceless. Two such bottles, from the late 1700s, remain at the estate, locked away “in the castle,” as our guide told us.

She spoke English, continually furnishing our group of three with information, and led us straight to the barrel room, a subterranean chamber containing several hundred new-oak casks and, within them, the three latest vintages of aging wine. Just weeks prior, our guide said, the winery’s technical team had blind-tasted from the barrels and eliminated about half of 2011′s crop as sub-par. This volume would be sold away to local wine merchants for the anonymous bulk wine trade.

“They will be labeled as ‘Sauternes,’ but not as Chateau d’Yquem,” she explained.

We returned to the tasting room, a spare but elegant chamber in which my wet socks and damp shorts were slowly becoming dry again, and here, at last, out came the wine—a bottle of 2008 that had been open and breathing for several hours. It was colored like honey and pine sap, and it glowed even in the dull light of the gray gloom outside. Our guide served us each a tiny two-ounce taste that would have cost 50 bucks in a wine bar.

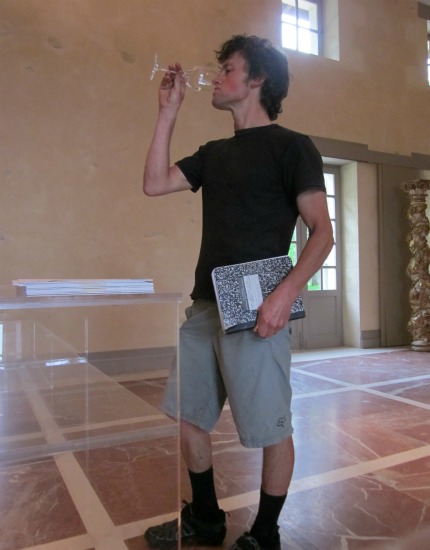

At the end of his guided winery tour, the author downs the last sip of Chateau d'Yquem he is ever likely to taste. Photo by Alastair Bland.

We swirled, then sniffed in an intoxicating blizzard of tropical fruit aromas. Strangely, much of this complexity of the Sauternes sweet wines is attributable to the mold of Botrytis cinerea, which is feared by most winemakers, but in the microclimate of Sauternes, it produces various sublime effects. For one thing, the mold causes the grapes to shrivel—water loss that magnifies sugar levels while decreasing the overall wine yield. At harvest, only grapes fully affected by the right species of mold are selected. So much unwanted fruit is discarded at harvest that each vine on the property—manually tended, pampered and all but massaged for months—ultimately produces just a single small glass of wine per year.

We continued looking at the golden wine, almost too intimidated to drink. Our guide said she had once tasted a bottle of the 1904, and she shuddered in a sort of bliss at the memory, recalling that it had tasted like brandy, fig and raisins and was colored like amber (funny, the reasons we so cherish wine). The remaining older bottles are things only to dream of. The pair from 1784 and 1787 that still dwell in the estate library, shaped like perfume vials and etched with Thomas Jefferson’s initials, will likely not ever be opened. And while each is more precious than you or me, whether they’re still good is not even certain. Another Chateau d’Yquem sweet wine of that era was sampled in the 1990s by a one-time owner of the property. He described the old wine as “drinkable.”

Finally, I summoned the courage for a swallow of Chateau d’Yquem. It was excellent. My notes indicate a taste of pineapple, guava, melon and maple syrup, and a thick and satisfying honey-like feeling in the mouth due to the wine’s sticky, sap-like sweetness. We each had just enough for three or four sips, and then the perfumey, delicious liquid was gone and already fading from our memories.

Table wine can be bought in bulk at many wine boutiques in France. Here, a shopkeeper near Bordeaux fills a bottle with red Bordeaux. Photo by Alastair Bland.

After our tasting, I passed through Sauternes—a cute little village that would likely have been just another manure-splattered cow town if dumb luck, microclimatology and royal wineries had not showered the region in fortunes. And so Sauternes, though dressed in crumbling stone and old wood barn beams, is a lavish place of tasting bars and hotels. I walked into a small wine boutique, past all the bottles of aging, golden, honey-like wines and went straight to the bulk bin. “Vin en vrac?” I said to the proprietress. “Wee!” she answered, taking my empty plastic water bottle and filling it with common person’s red. I handed over two Euros and, still thinking about Sauternes, went away with a liter of bulk Bordeaux.

Tours of Chateau d’Yquem are free, include a tasting and must be arranged in advance. Contact the winery via the website.

Other fine wines of Bordeaux too expensive to taste:

Chateau Lafite. The most expensive bottle of wine in the world, as reported by Forbes, was from Chateau Lafite—a 1787, bearing President Jefferson’s initials, and which once drew at an auction 105,000 Euros.

Chateau Haut-Brion. Founded in 1525 and a producer of wine since the mid-1600s, Haut-Brion has been a treasured name of wealthy wine drinkers for centuries. Both John Locke and Thomas Jefferson praised its wine and the estate’s soil.

Chateau Latour. Just browsing the website of this princely palace makes you nervous you will knock over a bottle of red more expensive than a nice house. Age, reputation and scarcity are the driver’s of Latour’s huge price tags—though I’m sure the wine is great.

Chateau Petrus. Yet another local property whose recent vintages already sell for thousands, Petrus may produce the most consistently expensive wines in the world. Much of the cost comes from scarcity and plain prestige, though writer after writer all but sheds tears over the magic of the soil in which the vines grow—limestone containing fossilized starfish.

And for something more drinkable, drop in on Chateau Roquetaillade La Grange during the week. The winery is run by three brothers, also the winemakers, who will personally, and casually, host their guests. Here, you can ask all the basic questions of Bordeaux without fearing scorn: Is Pinot Noir grown here? Prohibited. What does “grand vin de Bordeaux” mean? A denomination guarded by a set of quality standards. What are the prime red wine grapes of Bordeaux? Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)