Tasteful Photography

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20110520090133gm_04021401-400x336.jpg)

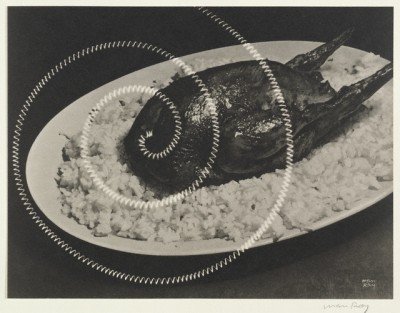

In my former life as an advertising art director, I observed how much work goes into making food look appetizing on film. Fine artists who photograph food as their subject put just as much thought and effort into how their images look as commercial photographers do, but often with different goals than making the viewer's mouth water.

An exhibition of food-related photographs called In Focus: Tasteful Pictures at the Getty Center in Los Angeles (where I am visiting this week) demonstrates how diverse those goals have been over the course of the medium's history. The 20 images, culled from the museum's collection, form a tasting menu of photographic approaches to one of art history's favorite subjects.

The earliest food photographs in the exhibition were made in the early 19th century, and were strongly influenced by still-life painting, with bountiful displays of fresh fruit or the spoils of the hunt. Virginia Heckert, the Getty's associate curator of photographs, pointed out that the sight of a hairy wild boar may not be appealing to the many modern-day eaters who expect their meat to be rendered unrecognizable by the time it reaches their plates. But at the time Adolphe Braun photographed Still Life of a Hunting Scene, in about 1880, the image would have represented the tantalizing promise of a feast to come (and today's proponents of "nose-to-tail cuisine" would probably agree).

The straightforward compositions of the still-life images from this period reflected how photography was done in its infancy, with a bulky camera on a tripod, using long exposures. All that changed, according to Heckert, when photography moved away from large-format to handheld cameras, around the 1920s and '30s. Artists were suddenly freed to point their lenses up, down or tilted at an angle. The Modernist photographs from this period treated food abstractly, often moving in for close-ups. "There is an emphasis on formal qualities," Heckert said. 'You think less about what is than the shapes and the shadows." In Edward Weston's Bananas (1930), bruised bananas are arranged to echo the weave of the basket they are in. In Edward Quigley's 1935 Peas in a Pod the diminutive vegetable is enlarged to monumental size, "honing in on their essence, or 'pea-ness,'" Heckert said.

In the documentary photography of the 20th century, food was just one of the aspects of life that gave insight into the people and places being documented. Weegee (Arthur Fellig) was known for chronicling the late-night goings-on of New York's streets, including its crimes, but he sometimes captured more lighthearted scenes, like Max the bagel man carrying his wares in the dark early morning.

Walker Evans's 1929 image of a fruit and vegetable cart captures a way of life that would soon be replaced by supermarkets. The way of life that replaced it appears in Memphis (1971), by William Eggleston, a close-up of a freezer that is badly in need of defrosting and stuffed with artificially flavored convenience foods: a contemporary portrait in processed meals.

Contemporary artists in the exhibition include Martin Parr, whose series British Food uses garish lighting and cheap frames on less-than-appetizing examples of his country's oft-maligned cuisine, including mushy peas and packaged pastries with the icing smashed against the cellophane wrapper.

Taryn Simon one-ups Parr in nauseating images with her image of the contraband room at John F. Kennedy airport in New York City. There, piles of fruit and other foods, including a pig's head, rot on tables awaiting incineration.

The largest, and most novel, approach to the subject in the exhibition is Floris Neususs's 1983 Supper for Robert Heinecken, a table-sized photogram. A photogram is an image created by laying objects directly on photographic paper and then exposing them to light. In this case, the paper was laid on a table set for a dinner party that took place in a dark room with only a red safety light. Two exposures were taken, at the beginning and end of the meal, so that shadowy images of the dishes, guests' hands, wine bottles and glasses appear. Heckert said the piece documents a performance by the diners, portraying what may be our strongest association with food, a shared celebration.

In Focus: Tasteful Pictures continues through August 22.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Lisa-Bramen-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Lisa-Bramen-240.jpg)