Spend Your Fourth of July Hominid Hunting

Celebrate Independence Day with a trip to one of America’s many archaeological parks

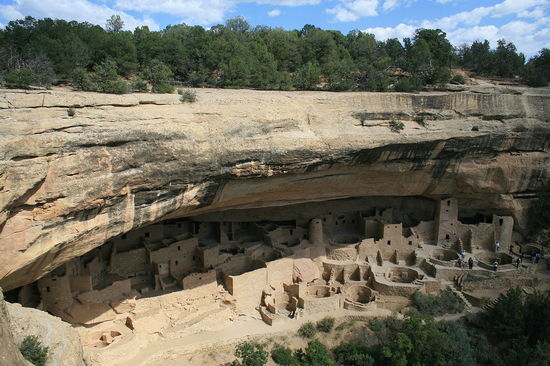

Cliff Palace at Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado. Image: Andreas F. Borchert/Wikicommons

The United States celebrates its 236th birthday this week. If you’re tired of the same old fireworks and cook outs, consider taking a trip to one of the country’s many archaeological parks to learn more about the people who lived in the U. S. hundreds or thousands of years before the Founding Fathers signed the Declaration of Independence. Here are a few suggestions:

Meadowcroft Rockshelter, Pennsylvania: This site may be the oldest known archaeological site in the United States, dating to 15,000 to 16,000 years ago. About an hour southwest of Pittsburgh, Meadowcroft offers tours of the rockshelter where you can see stone tools and the remains of fires that hunter gatherers made thousands of years ago.

Lubbock Lake Landmark, Texas: Not far from Texas Tech University, Lubbock Lake is an unusual archaeological site because of its complete, continuous record of human occupation over the last 12,000 years. The site’s earliest residents were the Clovis people, once considered to be the first human inhabitants of North America, and the Folsom people, who lived in the area about 10,800 years ago. Archaeologists at Lubbock have found Clovis and Folsom hunting and butchering sites, filled with stone tools and mammoth and bison bones. But excavations of the site are still ongoing, giving visitors a chance to see archaeologists in action.

Cahokia Mounds, Illinois: As a native of Illinois, I’m embarrassed to admit that I’ve never visited Cahokia, an area a few miles northeast of St. Louis that was first settled around 700 AD. By about 11oo, Cahokia had grown to be the largest pre-Columbian city in what is now the United States, home to as many as 20,000 people. (It was so big, in fact, that in 1250, it was larger than the city of London.) Cahokia was the center of Mississippian culture, a corn-farming society that built large, earthen mounds. Seeing such mounds, which served as platforms for houses, temples and other structures, is the highlight of a visit to Cahokia. The site’s centerpiece is the 100-foot-tall Monks Mound, the largest prehistoric earthwork in North America. If you don’t plan to be in Illinois anytime soon, there are plenty of other Mississippian mound sites you can visit, such as Alabama’s Moundville, Arkansas’ Parkin site (visited by Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto in 1541) and Mississippi’s Emerald Mound.

Mesa Verde, Colorado & Chaco Canyon, New Mexico: While the Mississippians were constructing mounds, people in the Southwest were building stone and adobe pueblos. The Ancestral Puebloans first came to Mesa Verde in about 550 AD. For 600 years, the Puebloans lived and farmed on top of the mesa. But near the end of the 12th century, they started to live beneath cliff hangings. Today, the park is home to 600 of these cliff dwellings. The largest is Cliff Palace, consisting of 150 rooms and 23 kivas, walled, subterranean rooms used for ceremonies. They didn’t live there very long, however. By about 1300, a drought forced the Pueblo people to find new territories to the south and east. (Despite the wildfires blazing across Colorado, Mesa Verde National Park is open to visitors.)

More than 100 miles south of Mesa Verde, Chaco Canyon was a major political and spiritual center of Pueblo culture from 850 to 1250 AD. Instead of cliff dwellings, the site is known for its monumental and ceremonial architecture, particularly multistory “great houses” made out of stone. A self-guided driving tour of the park passes by six of the site’s most famous structures.

Clearly, this list of American archaeological parks is by no means exhaustive—just a few places that I’d like to visit. Where would you like to go?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/science-erin-wyman-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/science-erin-wyman-240.jpg)