Nuclear Bombs Made It Possible to Carbon Date Human Tissue

The fallout of the nuclear bomb era is still alive today - in our muscles

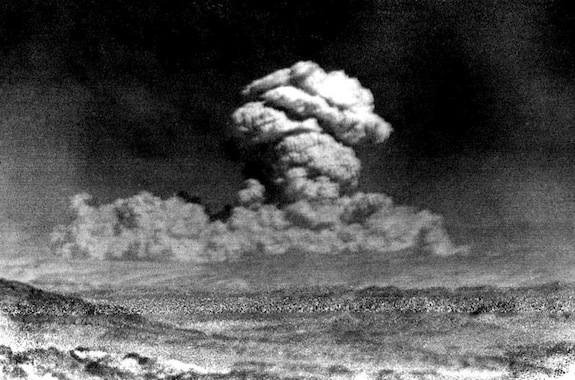

Image: UPI Telephoto

In the 1950s, the world tested a bunch of nuclear bombs, and today we’re still carrying around the evidence—in our muscles.

Here’s how that works. Between 1955 and 1963, the use of atomic bombs doubled the amount of carbon-14 in our atmosphere. Carbon-14 exists in the air, and plants breathe it in during photosynthesis. Animals eat those plants; we eat those animals; and carbon-14 winds up in our bodies, incorporated into our tissues. Every eleven years, the amount of that carbon-14 in the atmosphere would decrease by half.

So here’s the kicker. By measuring how much carbon-14 someone has in various tissues of the body, researchers can actually get an understanding of when those tissues were formed. They know how much extra carbon-14 was in the atmosphere each year and can compare the amount in a tissue with that number to find a pretty precise date.

What this means is that, by accident, nuclear experiments are providing a way for doctors to understand when tissues form, how long they last and how quickly they’re replaced. Here’s NPR on the most recent study to capitalize on this phenomena:

The researchers found that tendon tissue from people who were children or teenagers then contained high levels of carbon-14 attributable to the bomb blasts.

“What we see in the tendons that they actually have a memory of the bomb pulse,” says lead author Katja Heinemeier, a senior researcher at the University of Copenhagen and Jan Heinemeier’s daughter.

This same technique has helped researchers figure out how quickly neurons turn over too. Here’s Scientific American:

A new study relying on a unique form of carbon dating suggests that neurons born during adulthood rarely if ever weave themselves into the olfactory bulb’s circuitry. In other words, people—unlike other mammals—do not replenish their olfactory bulb neurons, which might be explained by how little most of us rely on our sense of smell. Although the new research casts doubt on the renewal of olfactory bulb neurons in the adult human brain, many neuroscientists are far from ready to end the debate.

And it’s not just humans either, here’s Robert Krulwich at NPR on how the carbon-14 spike teaches us about trees:

It turns out that virtually every tree that was alive starting in 1954 has a “spike” — an atomic bomb souvenir. Everywhere botanists have looked, “you can find studies in Thailand, studies in Mexico, studies in Brazil where when you measure for carbon-14, you see it there,” Nadkarni says. All trees carry this “marker” — northern trees, tropical trees, rainforest trees — it is a world-wide phenomenon.”

If you come upon a tree in the Amazon that has no tree rings (and many tropical trees do not have rings), if you find a carbon-14 spike in the wood, then, Nadkarni says, “I know that all the wood that grew after that had to be after 1954.” So botanists can use the atomic testing decade as a calendar marker.

But there’s a catch. Once carbon-14 levels return to their baseline level, the technique becomes useless. Scientific American explains that “scientists only have the opportunity to make use of this unique form of carbon dating for a few more decades, before C 14 levels drop to baseline.” Which means that if they want to use the technique, they’ve got to act fast. Unless there are more atomic bombs, and nobody really wants that.

More from Smithsonian.com:

Building the Bomb

The U.S. Once Wanted To Use Nuclear Bombs as a Construction Tool

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rose-Eveleth-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rose-Eveleth-240.jpg)