The Best in Fashion History: Penny Loafers, Forgotten Suitcases and Hermès Scarves

Three good reads to accessorize your daily routine

![]()

The Bass Weejun loafer is not named after a Native American tribe.

Suitcases sometimes are time capsules.

And a postal worker can design high-end scarves.

What follows is Threaded’s second blog roundup of sartorial curiosities from around the web, turning on their head assumptions about what we wear and why we hold onto things.

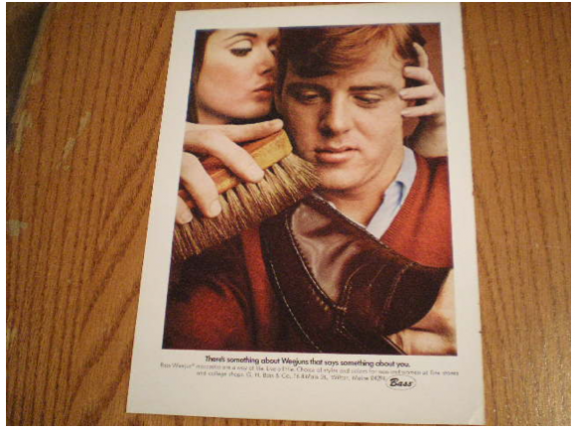

“There’s something about Weejuns that says something about you.” Bass Weejun ad, 1960s.

The classic loafer, and various bedazzled iterations of it, have come roaring back into public consciousness since residing on the feet of dressed-down corporates for the past couple decades. How the shoes originated with Norwegian fishermen, when preppy college students’ flocked to them and why they’re called Weejuns is explained by Nancy Macdonnell in her New York Times cultural history of the slip-on, “Loafing Around”:

Despite the Ivy League associations and moccasin construction, the loafer is neither American in origin nor named for a little known Native American tribe. Instead, Weejun is a corruption of “Norwegian.” What does that Scandinavian country have to do with the preppiest of American shoe styles? As it turns out, quite a bit: The loafer as we know it came about thanks to a combination of Lost Generation wanderlust and a growing and more general desire for comfort. Though Paris was the most famous destination for F. Scott Fitzgerald and his lesser-known cohorts, some of his peers journeyed further afield. Those who went to Norway noticed that Norwegian fisherman made themselves comfortable shoes that consisted of leather sides joined by a strip of leather across the instep like moccasins—still the way true loafers are made today.

Last year, photographer Jon Crispin’s Kickstarter campaign to document the neglected but intact suitcases of patients from the Willard Psychiatric Center in Willard, New York, caught my eye. Dating from the 1910s to 1960s, these suitcases were left at the asylum after it closed in 1995. Now, as time capsules, the valises, and the objects within them, tell the eerie and heartbreaking story of each patient’s life, many of whom never left the hospital after they were admitted.

Hunter Oatman-Stanford at Collectors Weekly interviewed Crispin last month about his project and the contents of the suitcases he’s been photographing in “Abandoned Suitcases Reveal Private Lives of Insane Asylum Patients.” The everyday objects Crispin photographed, which patients felt were essential upon entering Willard—green Lucite hairbrushes, a bright yellow alarm clock, a tube of shoe cream, a gold leather belt, a sewing kit, black-and-white photos, silverware—are fascinating bits of cultural ephemera on their own. In each self-contained parcel, the contents come to represent the patient. In the interview, Crispin recalls one particular story that’s stayed with him:

One of the last cases I shot was from a guy named Frank who was in the military. His story was particularly sad. He was a black man, and I later found out he was gay. He was eating in a diner and felt that the waiter or waitress disrespected him, and he just went nuts. He completely melted down, smashed some plates, and got arrested. His objects were particularly touching because he had a lot of photo booth pictures of himself and his friends. Frank looks very dapper, and there are all these beautiful women from the ’30s and ’40s in his little photo booth pictures. That really affected me.

Kermit Oliver design for Hermes.

Lastly, did you read the story that’s been circulating on the Internet about the Texas postal worker who moonlights as the only American artist to design Hermès scarves? Kermit Oliver, who’s in his 60s, has contributed 16 paintings to Hermès since the 1980s when Lawrence Marcus, the executive vice president of Neiman Marcus, recommended him. His scarf designs, painted when he’s not working the night shift at the Waco post office, take six months to one year to create and are highly sought after. His enigmatic lifestyle and reclusive art career was documented in “Portrait of the Artist as a Postman” in the October issue of Texas Monthly:

Kermit’s wife met me at the door. She wore dish-washing gloves and an apron decorated with red chile peppers, and her hair was up in a turquoise bandanna. “You know,” she said, “we’re not visiting people.” But she welcomed me in, offered me some orange juice, and led me down the creaky plank floors of a dark, cramped hallway. The walls were covered with art: images of exotic animals, elegant ranch-life pastorals in vibrant colors, biblical allegories. We passed a framed scarf, Kermit’s first for Hermès. Displayed behind dusty glass, it was a portrait of a Pawnee Indian chief on a bright-orange background, surrounded by childlike drawings of galloping horses with flag-toting riders.

Anything that you’ve read recently that you would recommend to Threaded readers?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/emily-spivack-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/emily-spivack-240.jpg)